Leaders: Economic flexibility may be key to election

Do any of the major parties have both the strategy and the persuasive ability to convince people of better times to come when they contemplate their general election ballot papers in May?

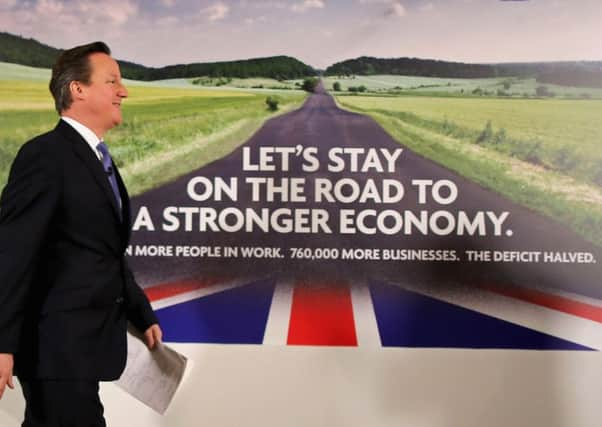

David Cameron’s strongest card is that the economy is definitely growing, and faster than in most other major economies, save for America. Most growth has come from rising domestic demand for goods and services, which should also be bolstered by something that is none of his doing – falling oil prices.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBrent crude prices are now exactly half of widely forecast levels and petrol pump prices are heading to about £1 per litre, cutting consumer fuel bills and transport costs by around a quarter compared to what they were a year ago. This is equivalent to a substantial tax cut, and while voters may be happy to spend their savings, boosting the economy, whether they will credit Mr Cameron remains to be seen.

The fly in the Tory balm is that the growth being signalled by headline GDP figures is not being felt by the broad mass of voters – real household incomes are still well below what they were before the financial crisis. Ed Miliband, of course, championing more curbs on bankers’ pay excesses and a tighter rein on household energy bills, hopes this will cause people to flock to Labour’s cause.

The response depends on how willing voters are to set aside any blame they attach to Labour for the undoubted mess the economy got into five years ago.

Here in Scotland, if the post-referendum shift from Labour to the SNP is any guide, Mr Miliband is struggling to cast off recent political history.

Current Scottish opinion polls certainly show no immediate desire by the new SNP converts to revert to old allegiances. This is despite current oil prices, which seem to be heading remorselessly lower rather than higher, having not so much blown a hole in the SNP’s flagship claims of more prosperity and less austerity with independence as torn the hull right off it.

Campaigning on this theme, begun already by Alistair Carmichael, the Lib Dem Scottish Secretary, may yet begin to make inroads. But he, and the other party leaders, have yet to turn round the disillusionment with British politics which seems to be gripping nearly half the Scottish electorate.

Providing a backdrop are the endless uncertainties in the world economy – potential eurozone stagnation and the crisis in Russia, to name the two biggest – which could cause more turmoil, upsetting these rickety economic applecarts. Having economic plans flexible enough to cope with the unexpected may well be the key to election success.

The call of the wildcat

Scots like to think of the Scottish wildcat as a unique and exotic predator, stalking Highland forests. Actually, it isn’t – different sub-species of the wildcat can be found across Europe, Africa and Asia. It is from these cats that all domestic felines, including those venerated by the ancient Egyptians, are descended.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNow nature seems to be taking some revenge for this man-made intervention into evolution. The domestic cat, in all its many varieties, has been interbreeding with its domestic wild cousins, including in Scotland.

Such is the extent of this cross-fertilisation that some experts reckon there may be no pure wildcats left. Tests on trapped wildcats have found all of them have genetic markers indicating that domestic felines have enjoyed a bit of life on the wild side.

And yet there remains the possibility that some wildcats have yet to mix with commoner moggies, and that the romantic notion of the noble Highland wildcat may still be true.

One of the attractions of the animal is its elusiveness. Many know of it, yet few have ever seen one. And the difficulties of its lifestyle – having to subsist on the small animals and birds it can catch – may ultimately ensure that any genetic weakness caused by over-familiarity with a softer cousin gets weeded out by natural selection.

We hope so. The wildcat’s domain in these isles is confined to the Scottish Highlands, which in turn is a marker for their wildness and uniqueness. Knowing that, when venturing into such a forest, you may be sharing it with, and being observed by, one of these predators adds a special thrill to being in Scotland’s more remote countryside.