Leader: Pursuing past abusers makes future safer

What good, they argue, does it do to have old wounds re-opened, and old men asked to account for deeds from decades ago, with such a slim chance of anyone’s memories standing the test of time to a degree that will satisfy a court?

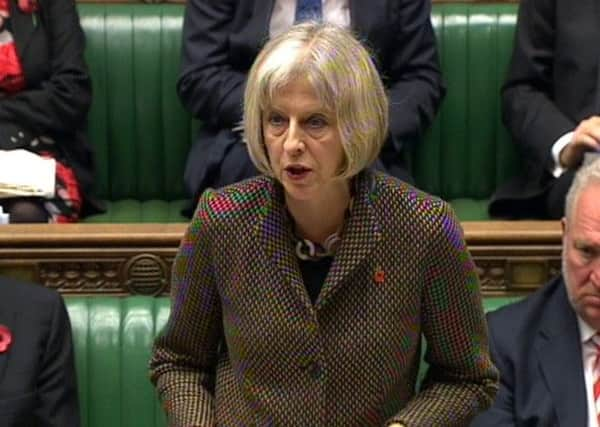

These people question the worth of exercises such as the inquiry ordered by the Home Secretary into cases of historical child abuse, which has struggled to find a chair deemed impartial enough by survivor groups. A parallel inquiry into the Home Office’s handling of such cases yesterday found no evidence that records were deliberately removed or destroyed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut other events yesterday demonstrated that the “let sleeping dogs lie” approach to historical cases of child abuse is simply wrong. Not only is it wrong, it is dangerous. Drawing a veil over the past puts the children of today, in Scotland in 2014, at a greater risk of falling prey to sexual predators. At Holyrood yesterday, MSPs heard ministers outline a national action plan to deal with cases of child sexual exploitation (CSE) in Scotland.

Following the horrific Rotherham case, in which 1,400 teenagers were exploited by men over a number of years while the police and child protection authorities largely turned a blind eye, all parts of Britain have begun looking for cases of similar behaviour in their own back yards. And in Scotland, police and social workers have found numerous examples of systematic CSE, which are only now beginning to proceed through the criminal justice system. Thankfully these have not been on a Rotherham scale but are on a scale large enough to suggest such behaviour has been happening for some time, apparently with impunity.

This is an area of law enforcement fraught with difficulty, not least because many of the young teenagers involved do not identify themselves as victims. It is sometimes only years later, with the hindsight brought by maturity, that they recognise how cruelly and cynically they were robbed of their innocence.

So, when we look at cases of historical child sex abuse, we should see them as not just an opportunity to achieve justice for past crimes – although the worth of this should not be underestimated. We should also see them as a means of protecting children now – firstly by demonstrating that there is no hiding place for perpetrators; and secondly by highlighting the need for vigilance on the part of child protection authorities, to avoid repeating past mistakes.

Because it is only by changing attitudes now and in the future that we can hope to ensure that victims of abuse and CSE are not failed by the system, as too many have been in the past.

Flowers of the forest

When a boy placed the final ceramic poppy in the moat of the Tower of London, completing what must rank as one of the most moving artworks of modern times, it was the culmination of an extraordinary 11 months of First World War commemorations.

One hundred years after the start of that conflict, this year’s acts of remembrance have shown how much it continues to haunt the modern imagination. The names of the battles – Passchendaele, the Somme, Gallipoli – are enough by themselves to conjure up the dread and horror of war.

Art has played a strong role in the year’s events, with powerful invocations of life in the trenches through the media of music, theatre, visual art and film, in addition to the popular triumph of the ceramic poppies.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut while these can help us look at the war anew, and with new perspectives, nothing is so powerful as the actual stories of the soldiers who lived through these experiences, and the soldiers who gave their lives.

The fragments of memory they left behind in the form of letters, photographs and diaries, as well as the indelible poems of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, retain their ability to invoke pity, all these years later.

The events and ceremonies of the past 11 months have been numerous – and perhaps there was a risk of empathy fatigue among some members of the public. But it was surely right that an extra effort of remembrance was made this year, of all years.

War is, sadly, part of our present as well as our past. It has lost none of its horror. It still demands we acknowledge the sacrifices made, and always remember.