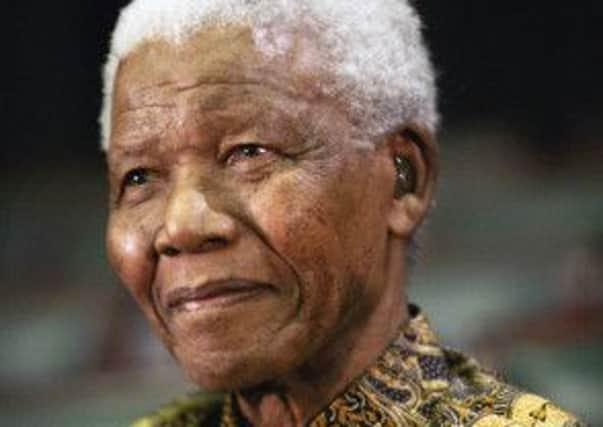

Leader: Nelson Mandela has left world a better place

That day, on February 11, 1990, when he walked out of the shadows of prison and into the bright sunlight of freedom, from the silences of confinement to the deafening celebrations of liberation, casting off shackles of mind and body to savour a world he had not seen for 27 years, is as sharp in the memory of those who experienced it as is the death of President Kennedy.

Sharper even, because this was a joyous event; not an end but a beginning, the start of a new era in history. That day marked not simply the freeing of one man but the liberation of an entire people, the black and coloured people of South Africa, from the nauseatingly shameful oppression of apartheid. And it was the dawn of a new hope in the world.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat hope – that all people, regardless of the colour of their skin, could live together freely as equals – seemed distant and unrealisable in the South Africa in which Mr Mandela grew up. To those who were born after he was freed, that must seem an extraordinarily incongruous statement. But this was a country where white colonialism did not die in the face of its own contradictions, but instead strengthened into a perverted state where racial superiority, and inferiority became enshrined in law, custom, and daily practice.

This was a country where black and white people could not eat in the same restaurants, could not travel on the same buses, could not live side by side, could not be schooled together. Only white people had the rights that mattered, especially the right to vote.

Against this grotesqueness Mr Mandela devoted his life, becoming first a lawyer to fight for his people in the courts, and secondly, joining the African National Congress to campaign for apartheid’s end. Only when oppression and state violence intensified did he conclude that it was useless to talk of peaceful resistance and became leader of the ANC’s military wing.

While he vowed to avoid death while blowing up power lines and police stations, he was condemned by many, including Margaret Thatcher, as a terrorist and eventually seized, tried, and imprisoned for life in 1964. Yet his extraordinary charisma and leadership qualities somehow escaped through prison walls. He and the others who were imprisoned on Robben Island, a heat-seared Alcatraz, came to be seen as incarcerated for no “crime” other than having a black skin. His freedom, and only his freedom, came to be accepted by the world as the sole criterion for judging the end of apartheid.

Thus it came also that Mr Mandela was the focus of the world-wide anti-apartheid movement, despite his face being unseen and his voice unheard. Gradually the apartheid regime became isolated as world politicians, businesses and sport bowed to the incessant pressure and came to shun contact with South Africa.

Scotland can be proud of the part it played in that movement, by disrupting Springbok rugby tours, by renaming Exchange Square in Glasgow as Nelson Mandela Square and by bestowing on him, while still imprisoned, the freedom of the cities of Glasgow and Aberdeen. These actions may have seemed futile drops of water against the impervious implacability of the apartheid regime at the time, but as Mr Mandela observed when he came to Glasgow to give thanks in 1993, they added to a multitude of other drops from across the world to become a cascade, a torrent, and then a tidal wave which washed away the abhorrence.

His quite extraordinary forgiveness and compassion, the remarkable lack of vengefulness, and the big-hearted desire for reconciliation that he showed on his release and throughout the years of his presidency of his nation have led many to think of Mr Mandela as a saint. Saintly, yes, but a saint, no, say such contemporaries who knew him well such as Bishop Desmond Tutu.

Some of Mr Mandela’s assets, such as his complete loyalty to those who were loyal to him, led him to make less of his presidency than he might have. He was too loyal to those such as Col Muammar Gaddafi and president Robert Mugabe where some condemnation of their despotic behaviour might have eased some suffering. And he was too tolerant of the incompetence of some of his ministers, an incompetence which has warped into distressing corruption in the current government.

Mr Mandela’s passing may yet serve as a reminder of, and spur to achieve, the high standards he set. South Africans, and the world, will be fortunate indeed if his like is seen again.