Joyce McMillan: Why SNP leaders are Thatcher’s children

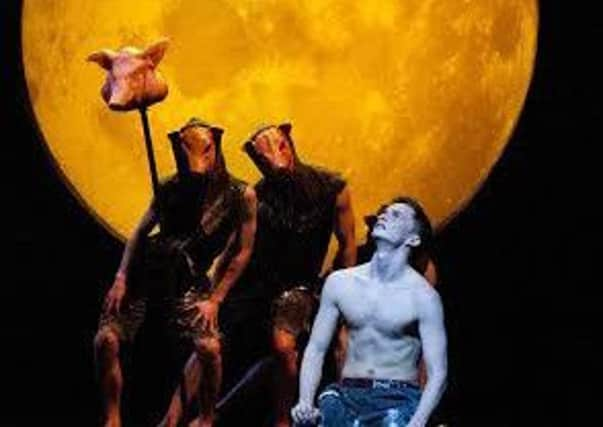

To the Festival Theatre, Edinburgh, this week, to see a touring stage version of William Golding’s iconic 1954 novel Lord Of the Flies, about a group of British schoolboys who rapidly revert to something like savagery, when they are stranded on a Pacific island following a plane crash.

I’m not quite sure what, exactly, makes this particular version of the story seem like such a pertinent commentary on current UK politics. Perhaps it’s the frequency with which the Westminster parliament, under David Cameron, is described as being like a boys’ boarding school, full of Tom Browns and Flashmans; or perhaps it’s just the huge Union flag on the tailplane of the wrecked aircraft that dominates the set.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhat’s clear, though, is that in an intensely topical way, Golding’s great novel dramatises the confrontation between two different styles of leadership.

Quiet, thoughtful Ralph, the elected leader, believes in democracy, debate, and building a consensus around the effort to improve the group’s chances of survival and rescue.

Posh, high-handed Jack, though - furious that he is not leader - embarks on a vicious wrecking project, training up his followers into a gang of blood-spattered hunters, and using the supposed existence of an enemy “beast” in the forest to justify an ever-more-extreme cult of unthinking violence, and obedience to his will.

And while no-one at Westminster has yet taken - at least in public - to stripping off, bathing in blood, and demanding that all loyal supporters dance a wild, rhythmic dance of triumph, it’s not difficult to detect the smartly-suited shades of these two different leadership styles in the current confrontation between David Cameron’s government, and the new Labour leadership of Jeremy Corbyn. “U turn? You turn if you want to - the lady’s not for turning,” Margaret Thatcher famously boomed at a Tory conference in the 1980s, setting a template for “strong” political leadership that has lasted a generation.

This week, though, we saw Labour’s new Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell frankly proclaiming from the dispatch box his own “embarrassing” U-turn on his promised support for George Osborne’s “fiscal charter”, binding future governments always to run a surplus while the economy is growing.

And although the conventional Westminster media were soon in full cry, dismissing this policy shift as a sign of Labour weakness and division, the new Labour leadership seemed less than bothered by the small backbench rebellion that ensued, or by the entrenched idea that politicians should never change their minds.

Jeremy Corbyn, after all, says he wants a more open, discursive type of leadership, in which policy can be freely debated, instead of being dictated by text message from on high.

And if exasperation with the control-freakery of recent party management was one contributing factor to Jeremy Corbyn’s election, so was the undoubted usefulness of the internet in contradicting the official versions of recent history so assiduously promoted by those in power.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs the great Czech writer Milan Kundera put it, the struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting; and no sooner had the Commons debate on the fiscal charter begun, than Twitter was alive with a short video clip of George Osborne’s withering and very witty speech against the similar fiscal responsibility measure introduced by the then Labour Government in 2010 - dismissed by Osborne as “vacuous and irrelevant”, and “an instrument to con the public.”

Now of course, there are limits to how far this quest for openness and flexibility can go; for every voter who watches the George Osborne video, and notes his own U-turn on the subject, there will be ten who only hear the media mood-music about Labour confusion and disunity.

It’s also clear, though, that when politics becomes too tightly controlled, too much concerned with the superficial presentation of a largely fictitious unity, then even the most casual of telly-watching citizens eventually become bored and alienated.

The truth is that no party in power can really avoid U-turns; the Justice Minister, Michael Gove, executed a highly significant handbrake turn only this week, when he withdrew the UK Justice Department from a contract which would have involved it in the running of the Saudi Arabian prison system.

And when those U-turns come to light, then it might be better, as John McDonnell suggested this week, for politicians to own up and show some humility, than to embark on one of those familiar logic-chopping attempts to suggest that a complete reversal of policy is actually nothing of the sort.

So if Jeremy Corbyn and his Shadow Chancellor have set out on a genuine if risky journey to see if they can free British politics from the PR-driven straitjacket of recent decades, then we in Scotland finally have to ask ourselves where that leaves our governing party, the SNP, as it gathers in Aberdeen this weekend.

For almost a decade, after all, the SNP have been able to bask in their image as the refreshing new kids on the block of British politics, while at the same time retaining a party structure with a very Blairite flavour, top-down and tightly controlled.

Now, though, the party’s claims to represent a radical force are being tested in at least three ways: through the increasingly obvious failure of its centralising policies in areas like local government and policing, through the arrival in the party of scores of thousands of people energised by the grassroots democratic upsurge of last year’s referendum campaign, and through the emergence of a Corbyn Labour Party with a real apparent interest in presenting a day-to-day challenge to the recent Westminster way of doing politics.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYou turn if you want to, said the lady; and there are now several obvious areas where the SNP should be turning, and fast.

Like the Labour Party of the 1990s, though, the SNP’s leaders are still Thatcher’s children to the extent that they take her model of leadership largely for granted, even if they reject her policies.

And if Scotland wants to see the kind of radical change in local empowerment and engagement foreshadowed by last year’s referendum campaign, it will therefore have to look far beyond the SNP for inspiration - including, perhaps, to Jeremy Corbyn’s experimental leadership of the Labour Party, however long or short it proves to be.