Joyce McMillan: Ordinary Syrian citizens forgotten

Once, in the spring of 2009, I spent a day in Damascus. I had arrived in Syria’s ancient capital the night before, without my bag, which was lost in transit. In a middle-class suburb called Dummar, at a concrete municipal theatre, there had been a controversial performance of David Greig’s play called Damascus, a Scotsman’s attempt to understand modern Syria through three contrasting characters encountered on a business trip. And the next day, before we left for Beirut, there would be a British Council seminar, designed to tease out some of the issues arising from it.

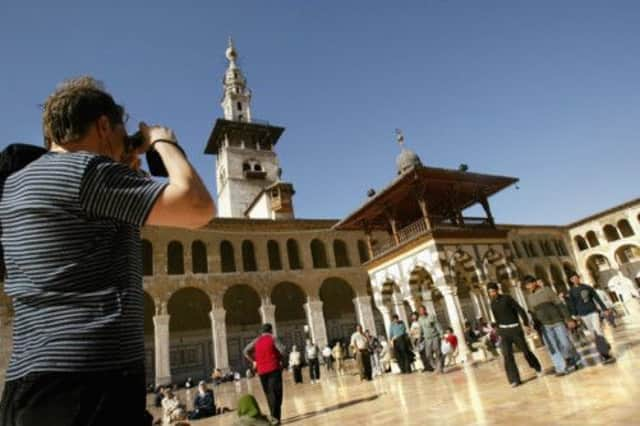

On this day, though, I was free, from 11 o’clock until early evening. So I ordered up a taxi, and went to the beating heart of the city, the old bazaar; and at its centre, the mighty Umayyad Mosque, perhaps the oldest religious site in the world, around which any tourist can wander, so long as the shoes are shed, and the body swathed in a modest gown.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was a Friday, Muslim holy day, and the mosque was packed with families enjoying their day off. In the great open courtyard, men stood chatting on one side of the space, and women on the other, much as men and women might have done at a British church social half a century ago; and across the courtyard sped dozens of small children on rollerblades, encouraged to play, and smiled on with great tolerance. I went inside, along the spacious back area of the huge prayer hall, where the women worship; there were digital displays showing the time in Damascus and Mecca, an imam somewhere leading the prayers, and, among the crowd, a mother and grandmother instructing a tiny tot in how to kneel, bow and pray.

The women wore the small half veils common among religious women in modern Syria; the Baathist or Arab Socialist government of Bashar al-Assad does not permit full veils, which it sees as backward-looking. The tiny tot, though, was dressed in full western style, with a vivid yellow ra-ra skirt and headband; and her mum and grandmother smiled broadly at her, and then at me, as she tried to put her chubby hands together, and imitate their movements.

And, of course, I cannot help thinking of that bustling, peaceful scene now, as Syria tears itself apart in an ever more brutal and complex civil war, and the West threatens military action. I hope that the little girl in the ra-ra skirt is safe, with her family; and I also hope that she will continue to live in a society where women can choose whether to be veiled, or to sport the big hair and vivid lipstick favoured by many professional women in Damascus, when I was there. In the city I visited, there was no mistaking the anger and despair of some young intellectuals and graduates against an authoritarian and highly conservative regime which offered few opportunities for the young, retained a fierce monopoly of power and influence, and had little regard for civic or personal freedoms.

Yet the majority of those who first came out into the streets in 2011, to demonstrate against the Assad regime and in favour of democracy and freedom, could never have dreamed of the violent chaos that would follow their peaceful protests, or of the fierce range of competing rebel groups which would enter the struggle over the spoils of rebellion. And it seems fairly obvious, now, that the pressing political need is to build regional alliances, backed by the UN, which can hold the ring and press these warring parties to the conference table, while the West – with its questionable colonial history in the region – stands well clear; that way, the little girl in the Umayyad Mosque has a chance of growing up in peace, rather than in a Middle East hopelessly polarised between an ever more violent Islamic fundamentalism, and a new breed of “modernising” leaders who are little more than stooges for western power. Meanwhile, though, the people of Syria suffer; from a civil war most of them never sought, and from a power struggle among groups none of whom truly represent their interests. After I left the mosque, that Friday afternoon, I set off for the airport, along a dual carriageway lined with families enjoying Friday-afternoon picnics under the dusty roadside trees, one of the few public woodlands left around Damascus. It took us hours to get to the airport and back, so packed were the roads with little pick-up trucks full of children and grannies and plastic chairs and paraffin stoves; in atmosphere, it felt like Britain in the 1950s, when working-class people first acquired a family car, and would head out on a Sunday for a drive, and a picnic by the roadside. And I would feel less despairing, as Syria begins to dominate our news headlines, if I felt there was any single voice of power, in this struggle, truly speaking for these people, and the hopes they may have been cherishing on that peaceful Friday afternoon, four years ago.

At the end of my day in Damascus, after three long, haggling conversations with three chain-smoking men in grubby airport offices, I found my bag, resting with two others on a patch of concrete beside the taxiway, silhouetted against a Damascus sunset. The bureaucracy was ridiculous, and possibly corrupt; I thought it needed reform, dialogue, education, agitation, exchange, transparency, democracy, all the forces that traditionally cleanse and change regimes that have been in power too long.

It never occurred to me, though, that it needed, or would suffer, the kind of cruel devastation now sweeping too many parts of Syria, and threatened by the Assad regime, the rebel groups, and the western powers alike.

For that kind of destruction is too often claimed to be in the interests of the people; while in fact it reduces them to mere collateral damage, lying dead or wounded on the airport road to some strategic goal which they do not share, and which – once the war is over – will doubtless prove to have been largely irrelevant to them and their loved ones, and to their best hopes for a life of freedom, security, and peace.