Joyce McMillan: Miliband gets the Thatcher feeling

YESTERDAY morning, in a lecture hall in London, Ed Miliband stood up to make what had been widely advertised as his “comeback speech” after a torrid week or two in Westminster politics. The “comeback” was necessary because after a lacklustre Labour Conference back in September and a recent storm of fiercely personal criticism in the media and in his own party, Ed Miliband’s leadership was said to be in doubt.

Voters, when approached by opinion pollsters, had started obediently to mirror the view that he is “weird” and “not prime ministerial”, creating a classic Westminster feedback loop of rumour and speculation; and meanwhile many of Miliband’s supporters started to complain about pejorative media coverage designed to undermine his position and misrepresent his character. The irony of this chorus of complaint was not lost on Yes supporters in Scotland, of course, many of whom felt moved to ask where Labour had been during the referendum campaign, when Alex Salmond and the Yes camp were subjected to the same kind of treatment, often by the same sections of the media.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYet it’s perhaps also important not to lose sight of the larger truth that if the Yes campaign came under attack because it was perceived as representing a threat to the Westminster system in its present form, then Ed Miliband may now be coming under attack for roughly the same reason.

For yesterday morning, the Labour leader made a powerful centre-left speech of the kind UK politics now urgently needs, denouncing the Tories for their devotion to a form of free market economics that has long since ceased to serve the interests of ordinary people in Britain, confronting UKip and their “wildly wrong” answers to Britain’s problems, and promising a comprehensive list of centre-left policies designed to create a fairer Britain, including 200,000 new affordable homes a year, a steady increase in the minimum wage and the repeal of the Coalition’s notorious Health And Social Care Act of 2012.

CONNECT WITH THE SCOTSMAN

• Subscribe to our daily newsletter (requires registration) and get the latest news, sport and business headlines delivered to your inbox every morning

Whether Miliband will ever have the chance to implement his programme, though, is far from clear. As he points out, the election of a Labour Party with this kind of manifesto will be bitterly opposed both by the “vested interests” he vows to confront – notably the banks and the giant power companies – and by sections of the UK media that are used to getting their own way when it comes to elections, and to “monstering” Labour leaders who step out of line.

The Labour leader’s greatest difficulty, though, is likely to come not from obvious external enemies but from those in his own party who have never fully accepted his leadership and who show little sign of agreeing with his view that the age of neoliberalism – and therefore of the privatising “reforms” beloved by Blairites – is over.

It’s fairly obvious, from any kind of historical perspective, that the two main media charges against Miliband are nonsense.

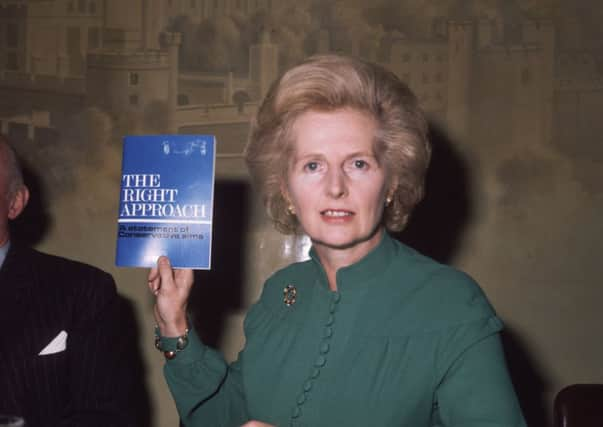

The Labour leader is certainly not unusually “weird” or unelectable; he gives every appearance of being a more intelligent, capable and caring politician than the present Prime Minister; and as for “weirdness” – well, some of us can remember just how “weird” Margaret Thatcher was as leader of the opposition, both in dress and manner, and how convinced many of her opponents were that her presence as leader in 1979 made the Tories unelectable.

What the media mischief-makers will not point out about Ed Miliband, though, is that the main ideological dividing-line in contemporary politics – between serious social democracy for the 21st century and a stubborn Bourbon-like adherence to the current neoliberal orthodoxy – now runs clean through the middle of the party he purports to lead, and is reflected in the daily whining of those who would rather have seen his much more Blairite brother David as leader.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd if you add to this complex problem of leadership the débâcle now facing the party in its traditional Scottish heartland, then Mliliband’s task in leading Labour to anything like a convincing victory in 2015 begins to look much more difficult.

Miliband may not have grasped it yet; but in aligning his Scottish Labour Party so closely with a No campaign based on little but reactionary scaremongering and a few rash promises, he and his colleagues made a possibly fatal betrayal of the Labour home rule tradition in Scotland, which was much more accurately reflected in the position of the trade union movement – ie vote for Scottish independence if you like, but continue to fight for socal justice no matter what. The result is that Labour seems likely, on present poll ratings, to lose upward of a dozen seats in Scotland next May.

And even if some Scots eventually make the traditional Westminster election shift back to the Labour fold, Miliband remains stuck with a Scottish party divided and demoralised after an ill-fought referendum campaign and now faced with a leadership choice between the arch-Blairite Jim Murphy – who seems more like an aspect of the problem, than any kind of solution – and two left-leaning contenders, neither of whom articulates Miliband’s kind of 21st-century social democracy as well as Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland’s SNP First Minister in waiting.

In terms of wresting power away from those who gave us the 2008 crash, in other words, and restoring some kind of economic and democratic balance to our society, an alliance between Miliband and Sturgeon would be something to see. For that, though, Labour would have to drop its ingrained allegiance to the British state in its present form, open its mind at least to the possibility of Scottish independence and start forming new progressive alliances that would have seemed unnecessary or unthinkable just a few years ago.

For the moment, it seems unlikely that those who have been briefing against Miliband over the last fortnight will ever give him the space to pursue any such solution. Yet with the tectonic plates of UK politics finally on the move, it would be a foolish observer who now said “never” to the idea of a future in which a restored Labour Party and the SNP might begin to map strikingly similar paths towards more just and sustainable times.

SCOTSMAN TABLET AND IPHONE APPS