Joyce McMillan: Little to sing about in devo plan

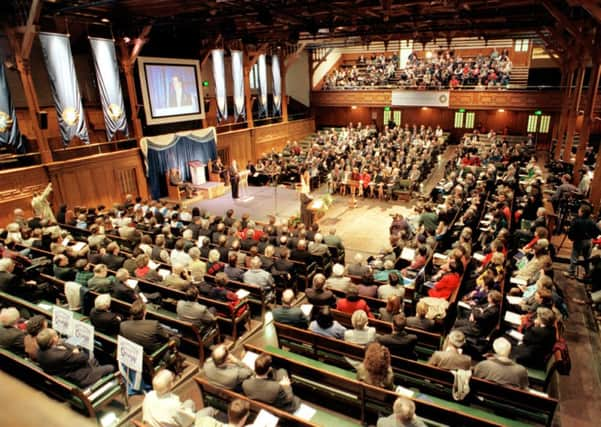

IT WAS on a cold day in November 1995 that I walked up the steps of the Assembly Hall in Edinburgh with hundreds of other people, to watch the launch of the final report of the Scottish Constitutional Convention, titled Scotland’s Parliament, Scotland’s Right; as I arrived, someone threw some sparkly party-dust over my face and hair, for the event truly did feel like a celebration. It’s worth remembering that at the time, most UK politicians were still dismissing the whole idea of devolution as absurd and unworkable; John Major then prime minister, described the whole thing as a silly political scam dreamed up at an Islington drinks party.

From where I was sitting on the Mound, though, it was obvious that this was something more like a quiet but determined popular revolt, in Scotland, against 16 years of deeply unpopular rule by the Conservative Party of the Thatcher era. The range of groups represented in the Convention was formidable, from political parties trade unions and local authorities to churches, women’s groups and green campaigners. And the result of the 1997 referendum, in which the radical and detailed Convention scheme for a new Scottish Parliament was approved by almost 75 per cent of Scottish voters, revealed the striking strength and depth of the movement for change.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAll of which provides a stark contrast to this week’s launch of the latest round of “devolution plus” proposals from the Scottish Labour Party, launched by Johann Lamont to an audience of journalists in the bland conference suite of an Edinburgh hotel. These are different times, of course; but it’s hard not to be struck by the relative smallness of the group of senior figures who produced the report and gave evidence to the commission, and by the lack of any real radicalism or ambition in what the commission has proposed.

The report is particularly weak, oddly enough, in the two areas which the Labour Party has chosen to foreground this week. Its proposal to increase the parliament’s general tax-varying powers has already been dismissed – not only by the SNP but by the pro-devolution campaign group Reform Scotland – as marking a very small advance indeed on the Calman proposals included in the Scotland Act 2012. The much-trumpeted power to raise the top tax rate above the general UK level, would, it is estimated, affect fewer than 13,000 taxpayers across Scotland; and would therefore have no impact at all on Scotland’s ability to address substantial issues of economic inequality.

And even more worryingly for the No camp, the language used by the report in its general defence of the Union – and often repeated by Johann Lamont herself – seems in complete denial about the radical shifted the ground of UK politics over the last generation.

To talk about the UK as a “sharing union” dedicated to ensuring social justice might have made reasonable sense at any time between 1945 and 1974. Forty years on, though, it seems almost politically illiterate to launch a proposal for the future of the UK which does not even acknowledge, never mind tackle, the grotesque and worsening structural inequalities that disfigure our national life, after a generation of neoliberal consensus at Westminster; or the democratic deficit caused by UK Labour’s historic shift to the centre-right, including its acceptance of the present UK government’s flawed austerity narrative.

Add to all these reservations the obvious difficulty of delivering on any of these proposals – in a Westminster system where no party is likely to enjoy an overall majority after the 2015 election, where the Labour Party is in any case divided over further devolution, and where a No vote will inevitably remove Scotland from the visible political agenda for at least a decade – and you have a proposal that is as unlikely to come to fruition as it is modest.

In the event of a No vote, though – and even in the event of Yes – it will fall to Scotland’s political and civil-society leaders to begin to salvage some creative and positive elements, for Scotland’s future, from the political wreckage of the referendum campaign; and here and there in the less well publicised pages of the Scottish Labour proposals, there are a few glimpses of ideas that might play a part in that process.

By far the most significant of these lie in the party’s decision to support a massive re-empowerment of local government in Scotland, with a decentralisation of revenue-raising powers, and of some substantial responsibilities. This proposal is no doubt driven primarily by visceral Labour dislike of the SNP’s centralising council-tax freeze.

A few years down the line, though, the hostage-to-fortune Labour has offered here could begin to combine with grassroots campaigns, and the work of thinkers like Scotsman columnist Lesley Riddoch, to raise the possibility of a new age of local government in Scotland, designed to address the abysmally low levels of democratic representation we enjoy by European standards, and the obvious problems of our ill-designed single-layer local government structure.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd if you add that decentralising vision to the hints of serious land reform measures now coming from both Holyrood and Westminster, and the sense of common cause across the north of Britain increasingly captured in internet banter illustrating the Conservatives’ obvious lack of concern for everyone north of the Wash – then you have an inkling of how a new post-referendum politics in these islands could begin to look. For whether the Yes campaign pulls off a historic victory on 18 September, or the dismal campaign staged by Better Together achieves a No vote it has not deserved, issues of genuine grassroots democracy and community self-determination, will be vital to our future.

And they will sit alongside those ever-more-urgent questions of land ownership and land use that no UK or Scottish Government has yet had the courage to address;.

In addition there is the question of how we should form new and effective relationships with those closest to us in England and elsewhere, in an age when new movements, new parties, and new cross-border alliances may be needed to reboot a broken global system, and to put it back on a footing that delivers a richer, fuller life for the many, rather than yet more luxury for an increasingly strange and isolated few.