Insight: Crucial lessons from 1975 Europe referendum

It’s a remarkably familiar story. A Prime Minister wins a new deal in the UK’s relationship with Europe before taking the matter to the people. He allows those cabinet colleagues who oppose membership to speak out against him. And, during the referendum campaign, increasingly wild claims are made by both sides as they fight a political battle that’s less about policy than it is about national identity.

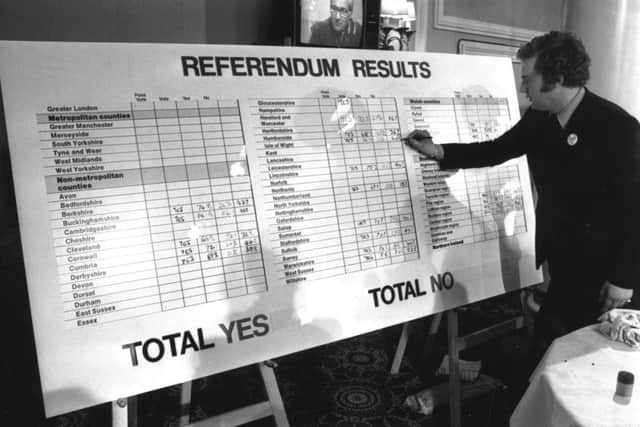

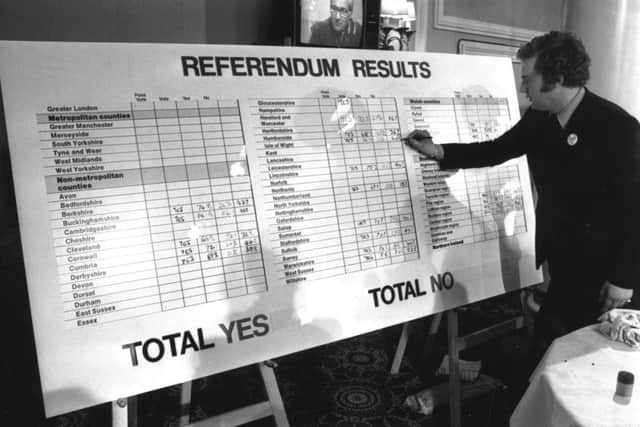

In the end, Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson won the day. Two-thirds of those who participated in the 5 June, 1975 referendum on the UK’s continuing membership of the European Economic Community – then commonly known as the Common Market – voted to stay in.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn many ways, David Cameron is reliving the experiences of his predecessor of four decades ago. Cameron has made much of winning concessions on the United Kingdom’s membership of the European Union. Like Wilson, the current PM has agreed to suspend the normal rules of collective cabinet responsibility, allowing government colleagues to campaign against his preference that the UK should stay in Europe.

And, as we have seen already, the debate on the issue shows little sign of rising above the tribal. Just as was the case in the 1970s, we see a Prime Minister acting not because he believes passionately that this is a matter of huge importance to all but because he wants to keep a divided party happy.

But while there are many echoes of 1975 in the current referendum campaign, there are stark differences, too.

Back then, Tory MPs were far more likely to be in favour of Europe. Substantial opposition came from the Labour benches.

The likes of Margaret Thatcher, who’d become Prime Minister in 1979, voted alongside pro-European Labour politicians, while the SNP was fiercely opposed. Nationalist politicians led the campaign for a No vote in Scotland.

Today, the SNP is united in favour of membership of the European Union, but party documents drawn up in 1975 suggest that continuing membership of the EEC would “strike a death blow to [Scotland’s] very existence as a nation”.

Press reports from the time reveal just how vehemently opposed the SNP was (though, privately, a number of the SNP’s 11 MPs were pro-Europe).

The SNP’s leader, Billy Wolfe, claimed that continuing membership of the Common Market would mean for Scotland “a political dark age of remote control and undemocratic government”, while Donald Stewart, who led the SNP’s parliamentary group, said the EEC “represents everything our party has fought against: centralisation, undemocratic procedures, power politics, and a fetish for abolishing cultural differences”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWinnie Ewing – who would go on to become a member of the European Parliament in 1979 – had an even bleaker vision: a vote to remain in the Common Market would be like signing a “death warrant”, she said, and would destroy any hopes of long-term Scottish prosperity. And, just as “Scotland’s oil” played its part in the 2014 independence referendum, so it was an issue in 1975. The SNP warned that Brussels would take control of North Sea oil fields and reap the benefits.

It’s certainly the case that Wolfe’s brand of Scottish nationalism – very much of the blood and soil variety – bears scant resemblance to the ideology espoused by Nicola Sturgeon today. Indeed, the party has done much to distance itself from some of the views held by leaders of the past. But at the heart of the SNP remains that overwhelming belief that Scotland would be better off going it alone, outside the UK.

Today, language about remote control and the loss of cultural differences is the stuff of the anti-EU party Ukip and the right-wing of the Conservative Party. Ukip leader Nigel Farage could use any of the lines trotted out by SNP politicians in 1975 and nobody would be in the slightest surprised.

But it is not just the SNP which has changed its view of Europe over the past four decades. Right-wing Tories were generally enthusiastic. The Common Market, as was, was about trade, and that chimed with Conservative support for entrepreneurialism.

And while Labour’s current left-wing leader, Jeremy Corbyn, and his cabinet colleagues will campaign for an In vote on 23 June, many of those figures who inspired his politics were staunchly against the Common Market in 1975.

Icons of the Labour left, including Tony Benn and Michael Foot, campaigned vigorously for the UK to break its formal relationship with Europe (an interesting quirk saw Enoch Powell, the former Conservative minister, then an Ulster Unionist, campaign on the same side as Benn and other left-wingers).

It is not difficult to explain the shift in opinion of those representing various ideological backgrounds. The EEC and the EU – although the former led to the creation of the latter – are different beasts. Put simply, the Common Market was about trade, while the EU is about legislation and regulation.

Left-wingers in the 1970s saw the Common Market as being for the benefit of “the boss class”. One veteran Scottish Labour figure said: “I was very young at the time. I’d campaigned in the 1974 elections and it was very common to find anti-EEC members in the Scottish party.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We might argue now that membership of the EU can help protect jobs but, back then, we were worried about how this might weaken the position of workers. What would this mean for the unions and so on? Remember the unions? They had power, then.

“And it wasn’t Labour who’d taken us in to the Common Market, it was Ted Heath and anything a Tory Prime Minister had done had to be a bad thing.”

Not, perhaps, the most sophisticated analysis but it should certainly ring true to anyone who recalls the particularly bitter Labour-Tory battles of the 1970s.

But it is the difference in the SNP’s position that may prove most significant to us, here in Scotland, this time around.

Given the Scottish Nationalists’ desire to break away from an existing union with England, Wales and Northern Ireland, the party’s doubts about remaining part of an even larger entity were understandable. Ideologically, rejecting of the Common Market made perfect sense.

In 1975, while UK voters voted by 67 per cent to 33 in favour of Common Market membership, Scots were more sceptical, with the final result being 58 per cent to 42 in favour. Voters in Shetland and the Western Isles were the only ones in the UK to vote against membership. England’s biggest No vote was 36.6 per cent in South Yorkshire, but nine of the 12 Scottish regions polled over 40 per cent for No, with the Western Isles up at 70.5 per cent.

Yet, in 2016, the SNP’s enthusiasm for membership of the European Union throws up apparent contradictions. Speaking in the House of Commons last Monday, the party’s Westminster leader, Angus Robertson, warned that an Out vote would mean turning our backs on “neighbours”. Given that Scotland’s closest neighbour is England – from which the SNP would still very much like Scotland to disengage – this may have seemed to some to be an unusual pitch.

Robertson’s substantial claim was that if the UK, as a whole, votes to leave the EU while a majority of Scots would prefer to remain, a second independence referendum will become inevitable.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAddressing the Prime Minister, Robertson said: “Do you have any idea what the consequences would be of Scotland being taken out of the EU against the wish of the Scottish electorate?

“I want Scotland and the rest of the UK to remain within the European Union. However, if we are forced out of the EU I am certain the public in Scotland will demand a referendum on Scottish independence and we will protect our place in Europe.”

He added: “It really matters that we can co-operate with our shared challenges from the environment and energy security, to workers and citizens’ rights.

“We should also never forget the lessons of European history, and not turn our backs on European neighbours who need help at this time to deal with huge challenges including the worst refugee crisis since the Second World War.”

In warning that a vote for Brexit could spark a second independence referendum, Robertson was simply repeating a line that’s been used, repeatedly, by Sturgeon in recent months.

Appearing on the BBC’s Andrew Marr Show last Sunday, the First Minister said a vote to depart the EU against Scotland’s wishes would “almost certainly” trigger another vote on the future of the UK. Should the Out campaign win the day on 23 June, she predicted an “inescapable” move by Scots towards leaving the UK in favour of protecting Scotland’s continued EU membership.

Sturgeon told Marr: “I think that would be the demand of people in Scotland. If you cast your mind back to the Scottish referendum, the No campaign then said if Scotland voted Yes then our membership of the EU would be at risk. That was rubbish then, but that was a key argument. If, a couple of years later, we find ourselves, having voted to stay in the EU, being taken out against our will, I think there will be many people – including people who voted No in 2014 – who would say the only way to guarantee our EU membership is to be independent.

“I personally know people who were passionate in their No vote in 2014 who would change their minds if we were in that scenario. That, I think, is just something that is inevitable.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, Sturgeon did add that she did not wish to see such a situation arise. “I hope,” she said, “the UK as a whole votes to stay in the EU for a whole variety of different reasons.

Perhaps one party insider, a veteran of several campaigns, can shed light on one of those – unspoken – reasons.

“If the UK does vote to leave, it doesn’t make winning a second independence referendum a sure thing. The one issue that caused us more trouble than any other during the independence referendum was currency and we’ve still not addressed the questions people have about it. We can’t have a second independence referendum where we stick to the line about us automatically entering a currency union with the rest of the UK because people didn’t buy it last time.

“So what would we do? Would we suggest a new independent currency? No, because, the EU would expect us as a new member to join the Euro.

“So, would we then pitch a campaign that meant we’d have to join the single currency even though it has the scabby touch, right now? This is all good rhetoric, but whether an Out vote would mean a second independence referendum in the near future is not all that clear.”

The complications the result of 23 June’s referendum might throw up for Sturgeon are as nothing, however, compared with those which might face Cameron. Should the Prime Minister fail to deliver the In vote for which he’s campaigning, there are doubts about whether he could remain in his job. He would, inevitably, be weakened.

Ambitious colleagues – not least Boris Johnson, who last weekend announced his preference for Brexit – might see an opportunity to move against him.

When Wilson called a referendum in 1975, he was confident that – with the help of his opponents in other parties – he would win out. Cameron may find that opponents in his own party play a significant role in his defeat. «

Twitter: @euanmccolm