I pray for today’s children, as terror and waste of new Cold War looms - Joyce McMillan

It wasn’t the first we’d heard of the nuclear threat, of course, or of the horrors of any possible nuclear war.

We knew that we lived on a knife edge of “mutual assured destruction”, which we were mostly able to forget; but in those days, following John F. Kennedy’s ultimatum to Khrushchev to remove Soviet missiles from Cuba or face war, it became impossible to ignore.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI remember going to school, just a few hundred yards down the road, and wondering whether the world would still be here at teatime. I wondered whether I would ever see my mother again; I sat staring up at the light fittings in the Primary 6 classroom, and imagining how they would look - shattered and swinging, I thought - after a direct hit on the base at Faslane, 30 miles away.

I also remember the huge surge of relief, a few days later, when Cuba was no longer the most urgent item on the news, replaced by an Indian-Chinese conflict in the Himalayas; and I remember the adult echo of that vast relief, two decades on, when - in 1989 - the Berlin Wall finally came down, opening up, for a brief hopeful decade or two, the possibility of a united future Europe, without walls or borders.

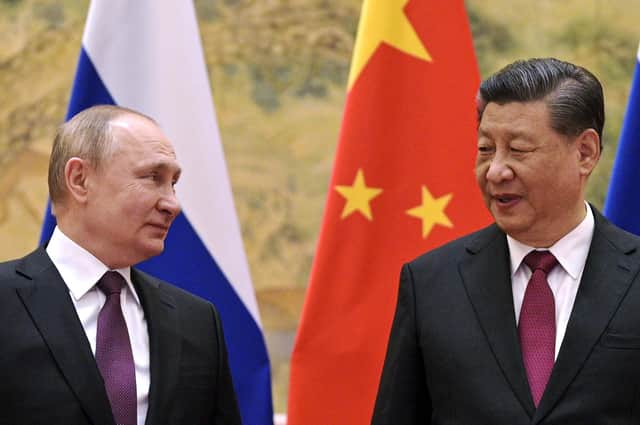

And it’s perhaps because of my Cold War childhood, shared with everyone of my generation, that I can feel nothing but sorrow and dread, as I watch the west and China - backed by its old ally Russia - shaping up for another Cold War, not least over Taiwan, in whose waters China is on manoeuvres as I write.

The nuclear threat has never gone away, of course; but now, we are re-entering the kind of era when a climate of hatred and mistrust between the world’s major powers invites an arms race that not only carries huge economic costs, but leads to ever more terrifying advances in weapons technology.

This waste of human endeavour, ingenuity and resources on the technology of death is heartbreaking enough in itself. The much-respected Stockholm International Peace Research Institute estimates that in 2021, global military spending stood at $2.1 trillion dollars, almost six times greater than current investment in renewable energy - which should, of course, now be the overwhelming priority for all of humankind.

When I remember the Cold War, though, it’s not only the waste and terror of the massive overkill of weaponry that I recall, or the malign influence on global politics of the huge military-industrial-security complex created by Cold War politics. I also recall the vast cumulative losses of human, intellectual, cultural and commercial exchange; and the joy with which people rushed to rebuild these links, as the walls began to crumble in the 1980s.

At the moment, our world is still strewn with memorials both practical and cultural to the mood of hope that pervaded international relations for two decades after 1990. From the gas pipelines linking Germany to Russia, to the beautiful Chinese hillside in the Botanic Gardens here in Edinburgh, and vast networks of academic and research connections, these links are now increasingly seen as problematic at best, and at worst dangerous. This week, the House of Commons even closed down its TikTok account, afraid that the Chinese-owned social media platform represented a security risk.

So here we go, back into a re-disconnected world of different internets, different media, and radically conflicting world views; a world where a myriad of commercial, creative and personal opportunities are lost, and where we once again end up asking questions like “Do the Russians love their children too?”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNone of this is to say, of course, that the west should simply put profit and exchange before any semblance of international legality. It is crystal clear that Russia’s shocking aggression in Ukraine must be resisted, and that China’s brutal disregard for fundamental human rights cannot go unchallenged.

The western powers, though, are not favourably viewed by most of the world’s nations, as they try to take a stand on postwar principles such as human rights and self-determination which they have themselves breached far too often, to be taken very seriously as their great defenders now.

And most importantly, we should be conscious of the massive Cold War costs - intellectual, commercial, political, creative and financial - that we are about to incur, at a time when we categorically cannot afford them, and when our priorities should clearly be elsewhere. So far, it seems Presidents Biden and Xi have at least succeeded in reaffirming that they will continue to cooperate on climate change, doing so again after their telephone conversation last week.

It is difficult, though, to see how such cooperation can long survive, amid a climate of increasingly warlike threats; and difficult to see how any western measures short of war would have much impact on the economic behemoth that is 21st century China, with its vast influence on countries across the developing world. I do not envy Joe Biden, or any other western leader who fully grasps the gravity of this situation, the task of trying to steer a path towards a more stable and sustainable world through such a gathering storm.

And I pray for the ten-year-old children of today, who already carry a heavy burden of anxiety over climate change, that they may not soon have to add to their fears a renewed threat of outright war between nuclear powers; a nightmare avoided only by a hair’s breadth many times during my youth and childhood, and now shadowing our futures again.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.