Hunting the ghosts in the machines - Jo McLean

One of 2022’s biggest social media trends involved the use of an AI-art generator, which uses a normal selfie and AI to generate overly perfected or fantastical portraits. ChatGPT – a search engine which uses AI to answer questions in a conversational manner – has also exploded in popularity and ruined the Christmas holidays of the Alphabet exec team.

These are just some examples of how the use of AI has grown throughout 2022 and is set to continue growing into 2023. AI can be a great tool to increase efficiencies and reduce (or even eliminate) human error in decision-making processes across all sectors, but it does also raise some obvious risks.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

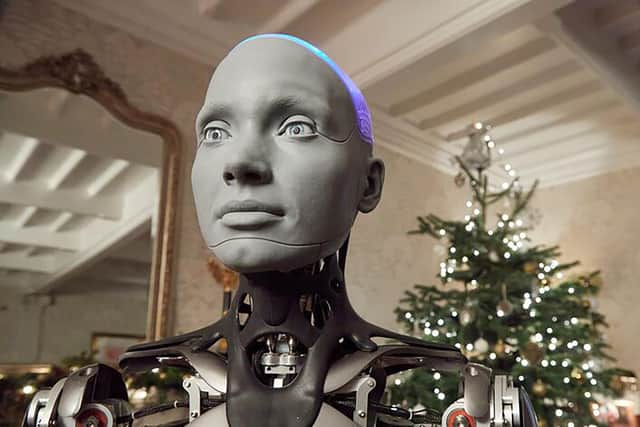

Hide AdSkynet, the doomsday AI in the Terminator movies, is the worst-case scenario and (hopefully!) extremely unlikely – what is more likely is that AI and machine-learning becomes burdened with the same bias found in human learning, and that the impact of such bias becomes greater as the use of AI increases.

There is also the general risk of the unknown and the lack of human rationale, emotional intelligence and creativity being applied to decisions which affect us on a large scale ends up in wrong, unethical, and harmful decisions ultimately being made. Not to mention the ability of AI technology to predict, influence or even control the decisions we think we are making.

This risk/benefit analysis forms the basis of most of the ongoing considerations by international bodies, governments and regulators as to how to appropriately manage and control the use of AI, without stifling the opportunities it may bring.

The EU’s imaginatively titled AI Act is working its way through the legislative process, although it is likely to be later in 2023 or early 2024 before this is finalised, followed by a two-year implementation period before it becomes enforceable law.

The AI Act is currently drafted to have extra-territorial application, so providers of AI technologies used in the EU (or marketed for use in the EU) will have to comply – even if the providers are not based or located in the EU. Therefore, Scottish businesses in this field looking to service customers and users in Europe or globally (including Europe) will need to be mindful of its requirements. It’s also possible the Act – similarly to the GDPR – could become the template used by regulators globally when developing their own regimes.

Both the UK and Scottish governments published national strategies for AI in 2021, but these are more about fostering an environment that encourages the creation of an AI industry, rather than the development of any new cross-sector regulation. This leaves a patchwork of existing legislation and regulations to govern how AI is developed and used. Existing equality, human rights and data protection laws apply to AI as they do to other activity which gives rise to direct or indirect discrimination, infringements on privacy rights or misuse of personal data.

As the use of AI grows, this approach will need to be reconsidered as these regimes have limitations and were not designed with AI or machine learning risks in mind. The equality and human rights regime provides us with rights not to be discriminated against, but these rights can only be enforced via a judicial system crippled by eye-watering delays and under-funding, and enforcement is often after-the-fact. This isn't appropriate in the context of AI, when discrimination may only become apparent once bias has already been learned and integrated into the system.

Data protection offers a more robust and over-arching regulatory regime, with the additional motivator of monetary fines. The UK data protection regulator has also issued detailed guidance on developing and using AI in a compliant manner. However, this is all through the lens of AI which uses "personal data" which identifies or relates to a specific individual and is less relevant to AI powered by anonymous datasets.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAll of this points to a need for appropriate regulation – even ChatGPT suggests a new, principles-based regulatory regime when asked this question. 2023 could be the year when we see this, not only in Europe but also perhaps in Scotland and the UK.

Jo McLean is a Managing Associate at Addleshaw Goddard