How the so-called 'Yorkshire Ripper' case revolutionised policing – Tom Wood

I dislike the title “Yorkshire Ripper”; it sounds honorific and, in any case, there are few similarities between his crimes and those of the original Whitechapel killer.

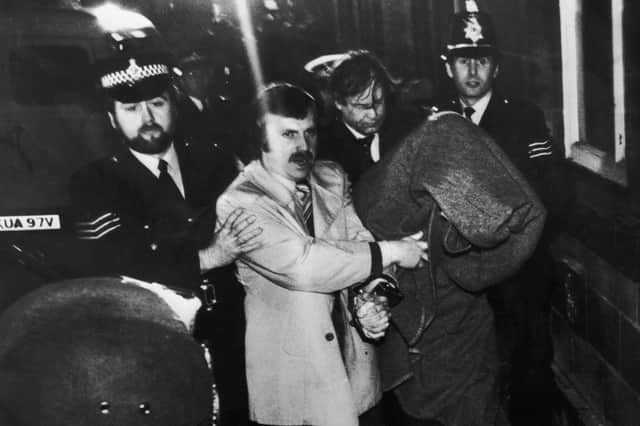

The truth is Sutcliffe was neither a clever or a well-organised murderer. He was brutal and lucky to be carrying out his crimes at a time and place when police forces were hopelessly ill-equipped to deal with such a pattern of offending.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe left in his wake dozens of primary and secondary victims who will never recover from his violence. But his crimes, or rather the botched investigation of them, brought significant change that benefits us still.

Few murders bring anything positive, the ripples of tragedy flow down the generations, marking families for years. In the last hundred years, only a handful can truly be said to have brought real improvements.

In 1935, the Ruxton case established forensic science in the mainstream of criminal investigation for the first time. Recently the 2013 conviction of Angus Sinclair for The World’s End murders brought important developments in DNA and much-needed reform in the double-jeopardy laws. There are a handful of other examples but none that compare with the changes brought about by the Sutcliffe case.

From the late 19th century, police used card-index systems for murders and major crime investigations. These were adequate for straightforward cases but hopeless for multiple crimes and incident rooms.

Thousands of index cards and multiple operators increased the risk of human error, overlaps and gaps. As it turned out, Sutcliffe fell through these gaps time after time.

Following the eventual conclusion of the case, a review was carried out by the hugely experienced Inspector of Constabulary Lawrence Byford. His recommendations changed the face of serious crime investigation in the UK and throughout the world.

From his report emerged the first computerised alternative system – the Home Office Large Major Enquiry System (Holmes).

It was expensive and problematic but eventually it was refined to become Holmes2, a fine investigative tool that police still use today. When considering advances in criminal investigation over the last 50 years, we usually focus on forensic science and DNA in particular. But the Holmes system is just as important.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut there was more. The Sutcliffe investigation finally exposed the myth of "the Great Detective” – beloved of crime fiction, but hopelessly flawed in crime fact.

In any major investigation, there are “red herrings”. In the Sutcliffe case, fake letters and an audiotape from a man with a North East English accent deceived the highly experienced lead investigator.

Police certainty that they were looking for a man with a distinctive accent was long on intuition, short on logic. It allowed Sutcliffe to slip through the net and cost lives.

Once Holmes came on stream, the system guarded against such lethal gut instincts.

Peter Sutcliffe was a disgraceful human being who perversely contributed to the significant advancement of criminal investigation.

Tom Wood is a writer and former Deputy Chief Constable. His books include The World’s End Murders – the final verdict and Ruxton – The First Modern Murder.