Henry Dundas's statue in Edinburgh should be torn down over slave trade links – Martyn McLaughlin

It should come as no surprise that the anti-racism demonstrations which have trained their ire on the nation’s ignominious ties with the Atlantic slave trade should focus on the Melville Monument.

The prestige of its location in St Andrew Square and its dizzying scale ensure it has long reigned as one of Edinburgh’s most prominent memorials, conferring an enduring power and authority upon its subject, which many people to this day mistake for the country’s patron saint.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSuch an exalted status could never be made for its actual subject - Henry Dundas, the 1st Viscount Melville - not even by those who leeched off his patronage during his lifetime.

A man whose legislative amendment proved pivotal in delaying the abolition of the slave trade – resulting in about 630,000 more people being enslaved – and who used troops to enforce the Highland Clearances, is rightly despised today.

It is unconscionable that a monument to his wickedness has been permitted to stand for so long without even a cursory reinterpretation of the fable agreed upon by his acquaintances. Having stuck their heads in the sand for years, Edinburgh’s city fathers hurriedly agreed on Monday night to the installation of a new plaque on the monument. It is an overdue response, and regrettable that their sudden cultural awakening has been prompted by panic and shame.

A missed opportunity

The council squandered the chance to open a dialogue about the monument in 2006, when it approved the use of £2.6m in public funds to reinvigorate the square, land which remains in the hands of private owners, whose silence on the issue has been deafening. So spare councillors your congratulations, and ask why it has taken them quite so long to salve their consciences.

In any case, the resolutions for change and promises of workshops and “new forms of words” are insufficient. Dundas should be banished from the skyline for good.

Ordinarily, I would side with those who caution against excising the darkest chapters of history. For a long time, Susan Aitken, the leader of Glasgow City Council, advocated renaming its streets to rid them of their slave trade associations. She has since arrived at the opposite view, reasoning that to do so would be “a form of erasure of black history”.

It is a measured response to a vexed issue. However, the Melville Monument is an exception. Not because its subject’s deeds were singularly abhorrent, but because the very act of its creation was a form of historical negationism.

Dundas was a dab hand in the grubby game of Georgian politics. He was one of the closest confidantes of Pitt the Younger, and wielded unchecked power as the president of the board of control of the East India Company, a position which allowed enormous wealth to flow into Scotland.

Delays and debt

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut the fealty pledged to him by his beneficiaries was finite, a fact disguised by the existing plaque on the monument which announces it was paid for “by the voluntary contributions of the officers, petty officers, seamen, and marines”. This is barely half the story.

Contemporaneous accounts of the monument’s creation in The Scotsman’s archives suggest that in the years following his death, Dundas, far from being revered, was remembered with apathy, if not hostility.

A committee formed to create the monument was established in February 1817, but donations proved hard to come by. After four years, it gathered just £3,430. Once the builder, William Armstrong, had been paid, there was not enough left to settle with the architect, William Burn.

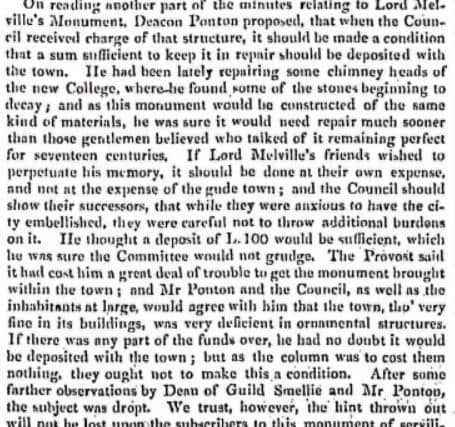

In a report of an Edinburgh town council meeting that same year, The Scotsman’s correspondent filed a caustic report about this “monument to servility”. He set out a forceful argument against the idea that the city should open its coffers, which betrayed a distinct lack of affection for Dundas among its people. “If Lord Melville’s friends wished to perpetuate his memory,” it stated, “ it should be done at their own expense, and not at the expense of the gude town.”

The committee’s fortunes went from bad to worse, which explains the five-year gap between the completion of the column and the installation of the statue at its summit. Some subscribers doubled or quadrupled their donations, but with debts exceeding £2,000, the committee was forced to obtain a £1,690 loan from the Bank of Scotland.

‘The future was against him’

A call went out to all Scotsmen who admired Dundas to contribute £5 a piece. It succeeded in raising only £209. The manuscript minutes book maintained by the committee shows that by 1834, some 17 years after the inauguration of their scheme, it remained in the red to the tune of £1,100.

With all voluntary contributions exhausted, the committee was left with no option but to ask its own members to meet the shortfall, a demand refused by several, and the situation drew out for a further three acrimonious years.

None of which serves as a particularly glowing tribute to a man many pronounced “Scotland’s uncrowned king”. If Dundas was held in such disregard a mere decade after his death, why persist with a monument to him two centuries later?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was not created as a symbol of the public’s appreciation, but sited on private land and paid for almost exclusively by a cabal who clung on to power and wealth in the dying light of the Georgian era.

Tearing it down would not eradicate all traces of Dundas – he is already represented by a statue in Parliament Hall, as well as an obelisk above Comrie, where he owned a sprawling estate. But the Melville Monument, towering 150 feet over Edinburgh, stands apart – an example of statuary’s ability to project potent myths.

Its removal would not rewrite history; it would correct a historical contrivance. Nearly 90 years have passed since Dundas’s biographer, Cyril Matheson, penned one of the first assessments of his place in Scotland’s past. “As with so many of the causes which Dundas defended,” he wrote, “the future was against him.”

Lord Melville should perch uneasily atop his fluted pedestal. The 21st century is finally catching up.

A message from the Editor:Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.With the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive - we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.Subscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions now to sign up.

Our journalism costs money and we rely on advertising, print and digital revenues to help to support them. By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Joy Yates

Editorial Director

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.