(Hand)writing is on the wall now

“If the use of the machine becomes general, handwriting will be as completely superseded as handsewing and the value of our present elementary teaching will be much modified,” the columnist warned.

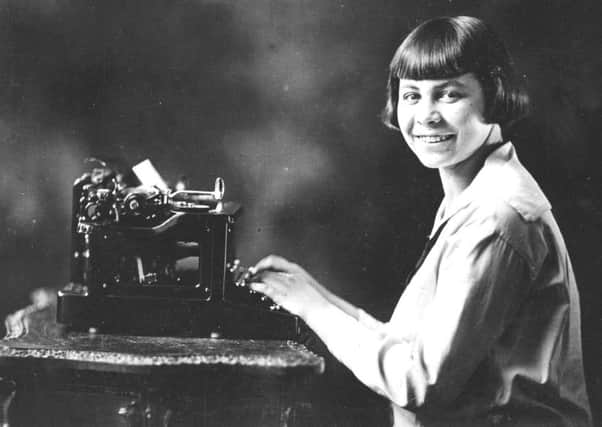

Shocking. Shocking indeed. For the author was correct. The creation of typewriters has indeed made handwriting quite redundant, for many people, at least. Yet the Victorian writer could presumably never have imagined to quite what extent the change would occur in what is actually a relatively short period of time.

Now, in 2017, I rarely handwrite anything.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI can compose an entire news story for this newspaper while out of the office, publish it directly to The Scotsman’s website and even send out a tweet from The Scotsman’s account, plugging it to our 120,000-odd followers. All using my pocket typewriter and, unless I am carrying out an interview using shorthand – a peculiarly old fashioned skill which makes journalists elsewhere in the world look at us Brits with a mixture of admiration and complete bafflement – without taking hold of a pen.

I could, if I wanted to, skip handwriting my shopping list and with the click of a few buttons, have my entirely weekly shop delivered to my door. Instead of handwriting calling cards to say hello to my friends, I can send them a quick text. Or a WhatsApp. Or a tweet.

Yet the article, printed on 7 January 1876, was written by someone who was probably only three or perhaps four generations older than me – perhaps a similar age at the time to my great great uncle, or my great grandfather, who, I have recently discovered, both worked in the newspaper industry in the late 1800s.

For a journalist to publish an article in that time, they would have had to write it out laboriously by hand, before making manual corrections and giving it to people like my ancestors, who were both stenographers for local papers, putting the words on to plates in a form that they could be printed on paper and eventually distributed to the public.

Incidentally, while this piece ran in the Portobello Advertiser, a Lothians weekly sold for a penny, the article, and many others in the same edition of the Advertiser, appears to have been unapologetically swiped from an original in the London Standard, an interesting observation of journalistic history in a modern age when news sources are under constant criticism for “borrowing” from each other online.

Yet it is not only journalists whose lives have been dramatically transformed over the course of a century and a half.

A study carried out in 2012 by printing firm Docmail found that a third of respondents had not been required to handwrite anything in the previous six months. Handwriting is dying out, along with spelling, as teenagers turn to autocorrect and predictive text to tap out their messages.

Personally, I have struggled with handwriting since I learned shorthand at journalism college more than a decade ago. Writing longhand just seems so laborious, when you can reduce a lengthy shopping list to a pile of (to me, at least) perfectly legible squiggles, taking a fraction of the time. NB it doesn’t work so well with birthday cards, or notes to my husband.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd the rest of the time, I like to type. I wouldn’t even know how to start writing a news story on a piece of paper – it would seem alien not to have the words appear in front of me on a crisp, white screen.

The author of the Portobello Advertiser article offers an astonishing insight into the future, warning that typewriters could make writing far easier, potentially tempting people to permanently put down their pen in favour of a keyboard. Yet he is confident that in practice, that will never happen.

“By learning to play on those keys, the performer may get to print faster than he can write,” he cautions.

“To persons afflicted with writer’s cramp it will be a luxury. And, upon occasion, a necessary; but we do not suppose that any but the most exceptional performers would ever realise the forty, fifty or sixty words a minute spoken of as possible with the use of this machine.”

What the author could not have imagined, however, is how portable this “typewriter” idea could become. Now, a typical mobile phone weighs less than five ounces, a mere nothing to carry around.

Yet, back in 1876, our Victorian friend is satisfied that it will not become widely used, due to the unwieldy nature of the machines of the time – not withstanding the high price of £23, equivalent to close to £2,000 in today’s money and therefore making it unaffordable.

“It would be a long time before the difference between a man’s writing and his printing would be worth twenty-three pounds to him, to say nothing of the fact that his printing must be done in one spot,” he explains.

Now, the idea of typing in one spot is laughable. Communication needs to be portable.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe cost is also not as ridiculous as he might think. Even today, people are happy to spend whatever it takes to have the latest gadget. The most expensive mobile phone is almost as pricey today as the typewriter appeared to the Victorian journalist – with the new model of the iPhone 5S selling on eBay for £2,000 in the early days of its release.

There are other phones, those encrusted with diamonds and gold, which can cost literally millions, like the $15m iPhone 5 Black Diamond. Imagine dropping that out of your back pocket and down the loo.

Thankfully, that could never happen with a typewriter. Maybe our Victorian journalist had the right idea.