From fictional Scotlands to Coventry and Massachusetts, here is my year in books – Laura Waddell

A sudden memory of reading on a train station bench; unremarkable then, strange now. Some have found it difficult to focus. I have spent more time between covers. Here are highlights, read not on trains and cafes and buses, but for the most part, in one chair, indoors.

In January, there was Coventry by Rachel Cusk, essays which lulled me with their patient, methodical tone. A passage I sent in jest to friends: “There are people who appear to have known from the beginning that driving wasn’t for them: often they are individuals society might label as sensitive or impractical or other-worldly; sometimes they are artists of one kind or another.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn February, on a self-organised editing retreat, Wintering by Stephen Rutt, a short book about geese. It weighed down my bag on long walks across (geeseless) beaches, the sand caught up in strong, cold east coast winds as though whisked.

A truly beautiful tale

But in spring, new things. A new pace. The shelves were bare of flour and lentils. I stockpiled books in one last mad dash the day before shops closed; for how long, nobody knew. There was comfort in sinking into Actress by Anne Enright, a novel about the fraught relationship between a midcentury star of stage and screen and her daughter, and the professional barriers faced by aging women. I lurked backstage, “a place of secret corridors and blind ends".

I read War and Peace, a dozen or so pages a night under a lamp, with online reading project #TolstoyTogether. We did not, by the end, emerge to happier times as hoped. But it was something to rely upon for its duration. The group also introduced me to The Maytrees, by Annie Dillard, set in the sand dunes of Massachusetts. A truly beautiful and heartfelt tale of a relationship evolving over decades.

The book trade started asking itself existential questions. Big bosses of retail argued the case that booksellers were essential workers too. Books make their own case. For pleasure, empathy, literacy, escapism, education, daydreaming, swashbuckling, and more.

But from the same quarters last year came arguments against paying shop floor staff a living wage. How essential, exactly? As Jonathan Gibbs describes it in Spring Journal, (yes, this spring – published very quickly by small press CB Editions), “And the main distinction now / Is not between the jobless and those with jobs / But in whether or not you have to leave the house […] the starker split between essential and inessential workers, / And therein lies true ‘social distance.’”

Exit makes its entrance

When stuck in a rut, I turn to translation. I enjoyed Loop by Brenda Lozano, translated by Annie McDermott, a fragmentary, offbeat novella about the search for the perfect notebook. And I was absorbed by A Man’s Place by Annie Ernaux, translated by Tanya Leslie, the story of one working man’s life and his more socially mobile daughter reckoning with it.

It was also a good poetry year. Tessa Berring’s mischievous Bitten Hair. Rendang by Will Harris, with lines I highlighted just as Covid was starting to sound serious, “I’d been dawdling, staring at people on business lunches. Restaurants / like high-end clinics, etherised on white wine". Tiny Moons by Nina Mingya Powles, short, illustrated reflections on food and Chinese identity.

A particularly sublime debut collection, however, was Life Without Air by Daisy Lafarge. From one stand-out poem, Fossil Dinner, “The moment is punctured by the arrival of the langoustine. / I raise my eyes from the tablecloth and drop my mouth: / The poor dish looks just like me.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn September my own first book, Exit, came out. But my first book launch, another matter entirely, will just have to be for the one I’m working on now (a novel).

After finishing Elena Ferrante’s latest, The Lying Life of Adults, infused with her idiosyncratic, menacing, familial energy, I got to Frantumaglia, collected interviews and snippets. What a rarity: utter devotion to refusing personal celebrity. A true artist, focused on the craft and not the ego. Another non-fiction winner was Feminist City by Leslie Kern, making the case for city planning to evolve beyond retrogressive assumptions of who uses public space.

It soon became clear festival tents would go unfurled from their slumber. Publishers gambled, shuffling around dates, schedules were up in the air. Workers were furloughed, except forgotten freelancers who fell through the cracks of Rishi Sunak’s scheme.

Skewering of debate culture

Millionaire artists say difficult times make for interesting art. I thought about this as I read the novel Waiting for Nothing by Tom Kromer, originally published in 1935, revitalised by small press The Common Breath. In stark, hard-boiled sentences, it evokes America’s Great Depression. Endless hunger, trying each night to find a ‘flop’ to sleep in, out of the rain. I couldn’t put it down.

At the peak of the heatwaves, I picked up one of the sharpest novels of recent years: The Topeka School by Ben Lerner, on parenthood and marriage within a toxic culture, so insightful on masculinity and personal and political communication, with some brilliant skewering of debate culture to boot. Another clever, queerer satire on academic jousting was Lote by Shola von Reinhold, set in an artist’s retreat which valorises minimalistic ‘Thought Art’, everything protagonist Mathilda is not.

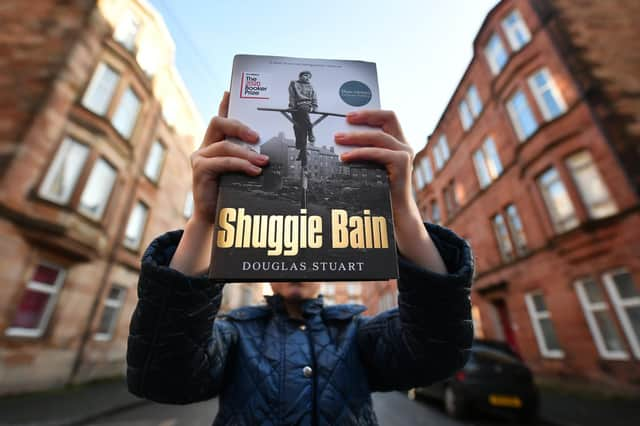

There was a multitude of fictional Scotlands to explore. Kirstin Innes’ character Clio burst from the pages of Scabby Queen, putting a flame-haired Scottish woman right at the heart of protest and art, just where they should be. The compelling Cat Step by Alison Irvine, about a bereaved single mother and young daughter trying to get by in Lennoxtown, pursued by social services. Set in the schemes of Airdrie, The Young Team by Graeme Armstrong had scenes that made me wince and smirk at their North Lanarkshire familiarity. And of course, Douglas Stewart’s Booker-winning Shuggie Bain.

What a year.

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.