Edinburgh's old Royal High School building risks the same fate as A-listed St Peter's Seminary – John McLellan

The A-listed St Peter’s Seminary was designed in the early 60s by Glasgow architects Isi Metzstein and Andy MacMillan who, says HES, “took the traditional monastic plan and reshaped it to form a totally modern idiom in terms of planning... with technical virtuosity they achieved a complex of buildings of amazing effects and sculptural quality”.

These days, it is also best-known as Scotland’s most prestigious wreck, “now reduced to a ruinous skeleton”, acknowledges HES. Built as a training college for priests, it was operational for less than 20 years and closed in 1980 when the Catholic Archdiocese of Glasgow could no longer justify the high running costs for a dwindling number of seminarians.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOnly last year, the church gave away the concrete remains for nothing to the Kilmahew Education Trust, a small group which aims to develop the site for education and give it “a new and vibrant future” for “renewal, reuse and reimagining the spaces and structures held within”.

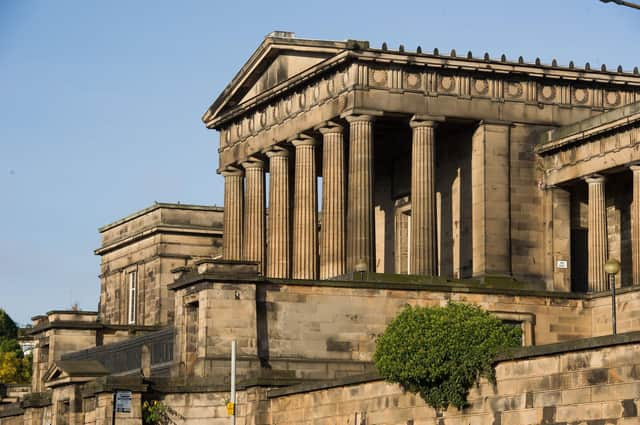

Not quite in ruins, but certainly in a very bad way is another A-listed educational building, described by HES as having a “unique and powerful combination of setting, massing and masterful use of classical architectural language”, and it too has attracted interest from a trust which, like Kilmahew, has set out to find an economically and culturally sustainable use which preserves the building and the site.

But the big difference between Kilmahew and Edinburgh’s Royal High School Preservation Trust (RHSPT) is the former has barely started and the depth of its pockets is unknown, while the latter has planning permission for its plan to turn the Calton Hill Georgian masterpiece into a music school, high-profile support and an extremely wealthy backer.

Who knows how much it will cost to bring St Peter’s into use; maybe its new owners do have a viable plan and hundreds of millions of pounds at their disposal, but the chances of the seminary eventually surrendering to the wrecking ball must still be high.

On Thursday, Edinburgh Council celebrated “a new chapter” for the Royal High, but councillors overlooked the music school plan and a new bid to turn it into a smaller hotel than the rejected scheme in which the authority was a partner, in favour of putting the building back on the open market.

Councillors also rejected the suggestion that the authority should find its own use for it so the imperative now, like the Archdiocese of Glasgow and St Peters, is to get rid. Some will argue that’s unacceptable and it’s the council’s duty to preserve it for the nation, maybe as some sort of community arts space for which the tax-payer is expected to foot the bill, but that’s a luxury it can ill afford.

It’s over ten years since the council contracted Duddingston House Properties to deliver a 125-bed “high-quality hotel of international standing”, but after planning permission for the much-criticised design was rejected by both planning councillors and the Scottish government, this week’s decision closes the chapter involving DHP, which is apparently so sickened by its dealings with the authority that it’s likely to walk away, with little appetite for a legal fight over the decision or the original contract to recover some of the estimated £4m spent on the project.

The RHSPT now has to decide whether it makes a bid for the site in the knowledge that going back to the market clearly indicates the council thinks it can get more than they were originally prepared to offer, and picking up what by some estimates is a £6m tab for basic but extensive restoration work the main buildings require.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat’s before the tens of millions more needed to execute what are very complex alterations to turn it into a new home for St Mary’s Music School and 300 mostly boarding pupils from all over Scotland and beyond. And it presumes a very left-wing council administration is happy about helping to enhance “Scotland’s national school of music” when it runs its own centre of musical excellence at Broughton High School only a couple of miles away.

Then again, what competition will there be when viable commercial use is now all but out of the question because the hotel option has been snubbed? “We know there are a number of interested parties out there,” said Edinburgh’s finance convener Councillor Rob Munn optimistically, but who they are, how many and how practical the alternatives are is unclear.

So where does that leave the school? Another museum/gallery idea like the Scottish National Photography Centre which 20 years ago put conversion costs at an optimistic £25m? The concept was attractive, the historic connections impeccable, it had the support of the late Sir Sean Connery and apparently some interest from photographic industry sponsors, and it got precisely nowhere.

As it stands, the flit of St Mary’s Music School to Calton Hill is now the only plan on the table and its team must demonstrate it was not just an elaborate ploy to destroy the hated hotel concept. According to accounts submitted to the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator, its main benefactor the Dunard Fund had £93m available as of March last year and as it is also committed to funding the Dunard Concert Hall on St Andrew Square for which costs are spiralling, finally committing to St Mary’s is a big decision.

This is the moment of truth for the Royal High. The conservation lobby and its preservation trust vehicle have seen off the hotel but unless it shows the colour of its money now, there is a real risk of the building suffering the same fate as St Peters. While the Royal High’s next chapter might be long, it could also be its last.

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.