Despite Kirk's disapproval, Scotland's long tradition of 'irregular marriage' proved remarkably resilient – Susan Morrison

My grandparents were married on December 31, 1928, in Bridgeton, Glasgow. A good day for a working man to take his vows. For one thing, it was a paid holiday for him. The banns had been read, they were wed by a minister with witnesses present. They were married “according to the forms of the Church of Scotland”. All very appropriate.

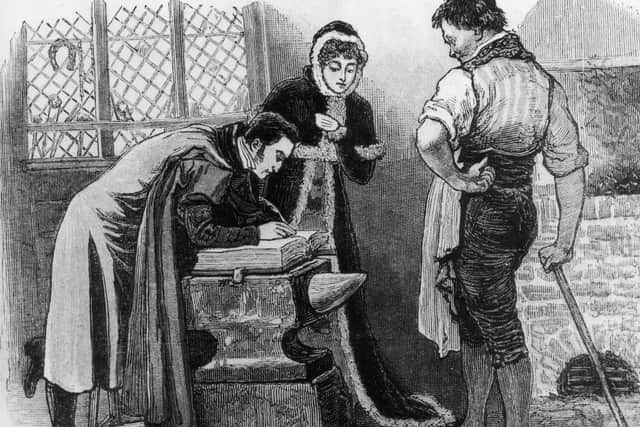

It wasn’t always like this. Scottish marriages, particularly in the 18th century, had more than a whiff of the drive-through Las Vegas wedding chapel about them, because alongside these regulated nuptials, Scotland had another form of marriage. It drove the Kirk to distraction. The irregular marriage.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEver since the Middle Ages, Scots could marry outside the Kirk just by announcing they were married, or they could “promise to marry”. It helped if there were witnesses. Finally, a man and woman could present themselves in public as married, “by habit and repute”. Marriage was a contract, not a sacrament. The Kirk, of course, didn’t quite see it that way. They tried to control the situation by hammering irregularly married sinners with stonkingly heavy fines.

Freelance marriage contractors

These loose arrangements were products of a rural community, but in the late 18th century the irregular marriage boomed, turbo-fuelled by two things. Firstly there was an explosion in the urban wedding pool when Scotland's young people increasingly left the farms, headed for the growing cities looking for opportunity, and met each other. We can all imagine how that went.

Secondly, around the same time, increasing numbers of clergy were losing their posts for one reason or another. Some set up as sort of ‘freelance marriage contractors’, capable of conducting something that looked like a regular service, and could provide paperwork that would appease the kirk sessions.

Couples could get hitched for considerably less than the fine they’d get hit with for fornicating without a licence, paying for the kirk or even waiting three weeks for the banns to be announced. You might have had good reason for a fast marriage. There’s the obvious one, of course. The fines for a child born out of wedlock were steep, as was the fine if they held the baby to have been born a little too sharpish following a regulated banns-and-all service. A licence proving you were married prior to conception was a useful thing to have.

Perhaps the groom was a seaman or a soldier bound for foreign shores and there was no time for droning announcements in kirk. They might actually have loved each other. Whatever the reasons, it was a good market for men with a bit of training and no scruples.

A different kind of prison wedding

In 1730, David Strang, or Strange, appeared in Edinburgh. He’d been chucked out of his parish for “misconduct”. For the next 14 years, to quote Leah Leneman and Rosalind Mitchison in their ground-breaking book, Sin in the City, Strang “almost held a monopoly on irregular marriages”. He wasn't a stickler for details. His certificates were riddled with misinformation and downright lies, but he was popular.

The Kirk became increasingly annoyed with Strang and tried to stop his business by putting him under a charge of “lesser excommunication”. Didn’t work. They escalated the ecclesiastical charges, but people kept seeking him out. Perhaps he had a great manner as a celebrant. Eventually, the civil authorities intervened and in 1738 Strang was slung into the Tolbooth. It tells you a great deal about the man that he promptly pestered the presbytery for “some method that may be thought up for his subsidence [sic, subsistence]”.

He wasn’t idle in jail. Couples came to the prison just to get married. Perhaps it had a cachet about it, like heading to exclusive wedding destinations in the Caribbean. He died in 1744, still in the Tolbooth and still marrying people. Despite his fame and obvious popularity, Strang had a rival, and one who was at large outside the prison gates, for a time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn May 1737 Janet Dods accused David Paterson of fathering her child before the kirk session of St Cuthbert’s. They were appalled, probably even more so because the errant father-to-be was a trainee minister at the Tron Kirk. Things got worse. That October the baillies broke into his rooms “with a hammer & a chezil” to find Paterson with a woman named Isabel. He said he’d brought her to his lodgings to mend his linen. Aye, right.

His career in the church was over. No matter. He took rooms in the sanctuary ground of Holyroodhouse, beyond the grasp of the baillies and the kirk. The constable of the abbey told the Canongate kirk that Paterson was in the “practice of marrying three or four Coupel [sic] a day”. He finally got nabbed and jailed in 1750, which, again, didn’t stop him marrying people.

In 1758, he became embroiled in a nasty business. He claimed he had married a lady of the night to a wealthy gentleman, just before he conveniently died, giving his ‘widow’ a claim on the estate. Not surprisingly, no one believed him. He was banished in 1759.

That dark side of irregular marriages was never far away. Women and children were often abandoned. Without those public banns, bigamy was easy, as were many other criminal activities. In Sin and the City, there’s the sad case of Janet Meekie in 1738 who quickly marries ‘John Blanket’ and spends the night with him. The next day he vanished, taking her plaid with him.

The free-booting irregular marriage slowly fell out of favour in the 19th century. Kirk weddings came to be considered to be more seemly, and increasingly so until very recently. These days, of course, Tolbooth cells and dodgy ex-clergy are out, but the wedding market is booming for Highland castles and Elvis impersonators.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.