Debate can help save country’s heritage

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

This year marks the 83rd anniversary of the National Trust for Scotland.

We are also midway through delivering a five-year programme designed to put the Trust back on a sustainable footing after much-publicised issues. We’ve achieved many of the needed reforms already but, even if there is still some way to go with our short-term goals, it’s now time to look further ahead. How can this grand old charity serve its core purpose of conservation in a rapidly changing world?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1931, when a roomful of the nation’s worthies gathered in Glasgow’s Pollok House and resolved to set up the Trust, it seemed a simple proposition. As one of our founders, Sir John Stirling Maxwell, put it, the Trust was to serve the nation “as a cabinet into which it can put some of its valuable things, where they will be perfectly safe for all time, and where they are open to be seen and enjoyed by everyone”.

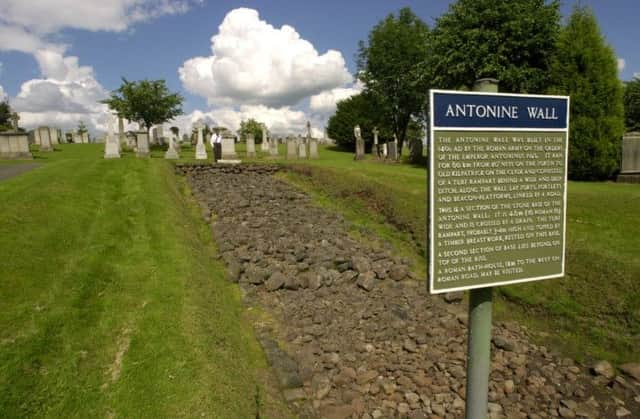

From the start, the Trust was never just about big houses: some of the earliest property acquisitions were the unspoilt wilderness of Burg on Mull, the remarkable 17th century townscape of Culross, a section of the Antonine Wall and Glencoe. The Trust pioneered the right of public access to the countryside long before it became enshrined in law.

Under the collective ownership of our 320,000 members, we now have 129 visited properties which straddle time periods that take in the earliest geological processes all the way to human activity that spans the mesolithic and the 20th century. With 400 islands and islets, 190,000 acres of countryside and wild land, 70 gardens, works of fine art and more than 100,000 artefacts in our care we are rapidly reaching a crossroads.

The cost of conservation is £44.2 million a year simply to stand still. We know that we need to spend another £4.6m a year if we want to meet our ambitions. As an independent charity we raise most of our income through our members’ fees and donors’ generous contributions. Contrary to popular perception, the public funding we receive in the form of grants, although much appreciated, is only a small proportion of what we need.

These costs always rise well ahead of inflation – specialist expertise required to repair 18th century masonry or restore mountain footpaths is not cheap or easily available, despite the vital assistance of 4,000 volunteers. Added to this are changing expectations – once a guidebook or a modest printed panel would have been all the interpretation visitors to properties would have needed. Now, as we have seen at Bannockburn, new generations reared on multi-media presentations expect and demand much more.

The rights of rural communities in terms of land reform are in the news. How does the Trust respond to this? Some argue we are just another “big landowner” and should cede land to communities and tenants – indeed, over half of the landmass of Iona, one of Scotland’s most significant places, has been transferred to crofters under right-to-buy legislation. But how does this square with our obligation to conserve important places for the nation as a whole for all time by holding them inalienably?

Taking another example, the David Livingstone Centre in Blantyre is not owned but is managed by the Trust. The property is vandalised regularly, which implies disconnection with heritage. Yet he was one of the most celebrated and inspirational Scots.

How can we find ways to help local people and wider communities engage with this place? How do we make this heritage relevant again in the 21st century?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe biggest question is: what is it people now want from Scotland’s heritage?

Answering that question will help determine the direction the Trust will take.

This month we are embarking on a debate with our members. We are open to all views about where the Trust needs to go if it is to remain vibrant and relevant. We want to hear from friends and critics and, after our October AGM, will reflect on what we have been told. To join the debate go to: www.nts.org.uk/heritage

• Kate Mavor is chief executive of the National Trust for Scotland www.nts.org.uk

SEE ALSO