David Bowie, my 'rebel, rebel', my hero, changed my life and helped us all make sense of the world – Susan Dalgety

“Never heard of it,” muttered the thirtysomething man behind the counter in our local electrical shop which sold a few LPs alongside toasters and washing machines. “Are you sure you’ve got the right title?”

It was the summer of 1972, I was 13, nearly 14. Like thousands of teenagers across Britain, I had “discovered” David Bowie, the man who was about to change our world.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI was an early adopter. I was captivated by his 1969 single Space Oddity, released just before Neil Armstrong walked on the moon. A rather solitary teen, in part through choice, but mostly because I lived on the Solway coast, 20 miles from my high school, I fell in love with his 1971 incarnation – a rather wan young man, with long flowing locks and long flowing dresses. I even joined his fan club, receiving a signed letter from his then wife Angie in return for my 25p postal order. I knew the words to Changes before anyone in my class had even heard of him.

‘Blokes in make-up’

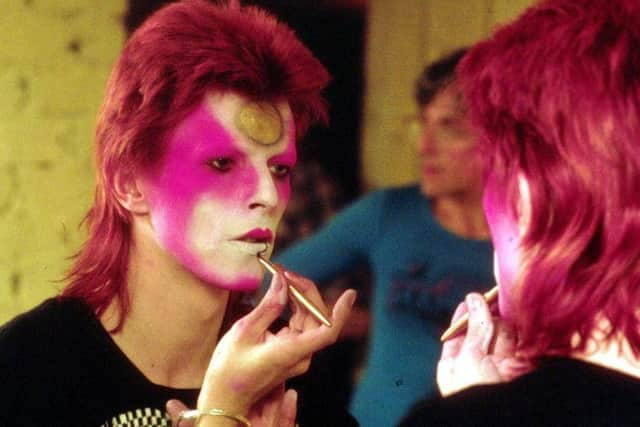

But it was Ziggy, with his spiky red hair and cheap make-up, who turned my life upside down. When he appeared on Top of the Pops in July 1972 to promote his single Starman, in a clip that is now legendary, he looked into the camera, pointed directly at me and warbled, “I had to phone someone, so I picked on you-hoo-oo”. DAVID BOWIE WAS SPEAKING TO ME.

My dad looked over the top of his tabloid and muttered something derogatory about “blokes in make-up”, and my mum continued knitting as if nothing had happened, little knowing that a skinny bloke in a garish jump suit had just turned her eldest child’s life upside down.

Fifty years later, as I survey the wreckage of our world through the various screens littered around our flat, the lyrics of Bowie’s Five Years play in an endless loop in my head.

“News guy wept and told us,

Earth was really dying

Cried so much his face was wet,

Then I knew he was not lying…

…We've got five years, my brain hurts a lot

Five years, that's all we've got…”

Boy or girl, it didn’t matter

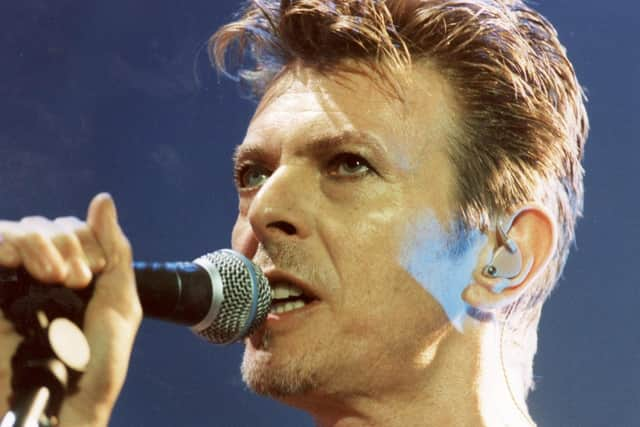

Tomorrow is the fifth anniversary of his death. He died, aged 69, from liver cancer, at home in his New York apartment in an unremarkable street in lower Manhattan. There was no funeral, no rock legend memorial. He departed this Earth as he had lived, on his own terms.

That was what David Bowie sang to me 50 years ago. He told me – a skinny, introverted, slightly strange young girl – that I could be who I wanted to be, my only constraint my imagination. And my supply of hair dye.

It didn’t matter if I was a boy or a girl, or both. I could wear satin and tat. I could write books. I could break free from the limitations of my working-class background. I could, like him, shape the future. More than any politician at the time, he spoke for my generation.

Over the course of his career, he said and did some stupid things, from his cocaine-fuelled Thin White Duke period when he flirted with fascism to his strange Christmas duet with Bing Crosby.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEven his much-loved anthem Heroes is as much a song about alcoholism as it is about freedom. “It (drinking) would kill me if I started again,” he told Jeremy Paxman in a 1999 interview.

But his frailties are nothing when compared to his influence on – and understanding of – the post-digital age. In that same Paxman interview, he predicted the impact the new-fangled internet would have on, well, everything.

“I think we are on the cusp of something exhilarating and terrifying… it’s an alien life form,” he told the sceptical interviewer. Twenty years later, we watch aghast as Trump unleashes his goons through the medium of social media.

“Music itself is going to become like running water or electricity,” Bowie told the New York Times in 2002. Today, my grandchildren think pop songs are something you find on YouTube, nothing more significant than a 30-second soundtrack for a TikTok clip.

A blueprint for dying

And he played with gender decades before today’s trans teens were born. As a young man, he dressed as he wished, flirting with anyone he found attractive, or useful. His announcement in a 1972 Melody Maker interview that he was gay (sometimes) liberated a generation.

But he changed people’s attitudes to sexuality with a smile. He never felt the need to dictate people’s pronouns, or claim that his love of make-up meant he was female.

“Why aren’t you wearing your girl’s dress today?” he was asked. “Oh dear,” he replied, “You must understand that it’s not a woman’s. It’s a man’s dress.”

And just as Rebel, Rebel is the theme tune to my teenage years, so his final album Blackstar is the soundtrack to the final decades of my life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe album, written and recorded while he was undergoing chemotherapy, was released on his 69th birthday, two days before he died.

“Look up here, I'm in heaven,” he sings on Lazarus, “I've got scars that can't be seen. I've got drama, can't be stolen. Everybody knows me now.”

He met his impending death as he had lived his life, with courage and style, offering those of us who had grown old with him a blueprint for dying, just as he inspired our lives.

The last public photographs of him – taken only a few weeks before he died – show a frail man, the shadow of terminal cancer on his face. Yet he is as beautiful as ever, smiling and waving and looking so fine.

Five years on, as we look on aghast at America’s tortured brow, at the lawman beating up the wrong guy, who is left to make sense of our world?

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.