Dani Garavelli: We must tackle world rape crisis

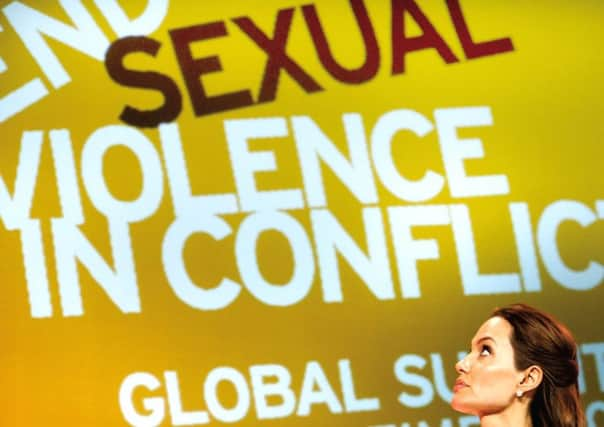

THERE has been a fair bit of sneering over the “star-studded” Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict held in London last week. One complaint has been that, with members of the public jostling to catch a glimpse of Hollywood A-listers Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt, it has felt more like the première of the actress’s latest movie Maleficent than a serious attempt to highlight and tackle the way rape is being used as a weapon in war zones all over the world. Foreign Secretary William Hague’s presence has been dismissed as if he were some kind of celebrity ligger as opposed to a veteran politician with a long-standing interest in human rights and a track record on this particular issue.

A second complaint has been that the whole event is pointless grandstanding. Rape is just one dimension of the dehumanising effect of war. It is inevitable. And even if it isn’t, how is to be stopped? Where governments have been over-thrown and the country is being torn apart by rival factions, who is going to police it? Might as well not bother trying.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI don’t buy into either of these arguments. Jolie is not some lightweight who has clung on to the coat-tails of a cause to garner credibility. In the 13 years she has worked as an ambassador for the UN Commissioner for Refugees, she has visited more than 30 war zones, highlighting the plight of the displaced. She also has a long-standing interest in violence against women (Maleficent, a children’s film, contains a scene which is apparently a metaphor for rape) and if her fame helps focus the world’s attention on an event that would otherwise have made a few column inches, then good for her. Far from eclipsing her message, the media obsession with her clothes and her body shape merely reinforces how far society has to go in its attitudes towards women. Criticism of Hague for attending the convention as Mosul fell to Isis militants seems to overlook the fact that it is in precisely this kind of chaos that the rape of civilians goes unchecked.

At the very least, the convention has raised awareness of the scale and psychology of sexual degradation in conflict. Where once, perhaps, rape in war was sporadic and opportunistic, it is now carried out on a mass scale as part of an orchestrated military campaign. Rape is always about power rather than sex; but in war zones it is about controlling entire populations. In Bosnia, it was used as part of a wider strategy of ethnic cleansing with soldiers trying to impregnate women with Serbian babies. More recently, sexual violence has been perpetrated on a mass scale in south Sudan, where it is said to have taken place under the noses of UN forces, and in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where official figures show 12 per cent of women have been raped at least once. The convention gave both victims and perpetrators a voice. It heard women describe the terrible degradation of being gang-raped and soldiers justify their actions. “When you rape, you feel free,” said one.

No-one listening to Jolie over the past few days could continue to labour under the illusion that rape is an inevitable by-product of war or deny that it flourishes in a culture of impunity. As for the summit’s power to effect change, well that’s less tangible. But if it can build on work done during the G8, which saw 144 countries sign up to a declaration that rape in conflict is a breach of the Geneva Convention; if it can help make sexual violence as unacceptable as chemical weapons, then that is something.

Where the conference is open to criticism is in western countries’ underplaying of reprehensible behaviour on the part of their own armed forces, both in terms of the rape of women in war zones (US soldiers in Iraq) and within their own ranks. In 2004, a report found almost one in three US women veterans had been sexually assaulted while serving. Assurances that the problem is being taken seriously – Barack Obama has spoken out on the issue – are undermined by the fact that, of the 5,061 incidents reported in 2013, only 484 went to trial and there were just 376 convictions.

In the UK, too, it seems a blind eye is often turned to the shoddy treatment of women soldiers. Last year, an inquest heard Corporal Anne-Marie Ellement had hanged herself after the army decided not to prosecute two servicemen she claimed had raped her. She said she had been the victim of a bullying campaign after making the allegations. If the military treats women in its own ranks this badly, it is in no position to ensure civilians in foreign war zones are protected.

Hague’s avowed concern for those raped in conflict is also undermined by claims the UK is deporting Tamil asylum seekers who have been subjected to sexual assault by the security forces in Sri Lanka.

Sexual violence is a growing problem globally. The world has looked on in horror as India has been gripped by what appears to be a rape epidemic, but even in Glasgow thousands of women last week took to the streets to protest against a spate of sex attacks and the country’s poor conviction rate.

If we are to take a global stand on the use of sexual violence as a weapon, then we ought to get our own house sorted. Rape is not inevitable, neither here nor abroad, in peace or in war. It is the result of a lust for power and a cultural apathy that lets men get away with it. That’s a message we need to absorb ourselves, even as we preach it to the rest of the world.

Twitter: @DaniGaravelli1