Dani Garavelli: Peace in Northern Ireland on trial

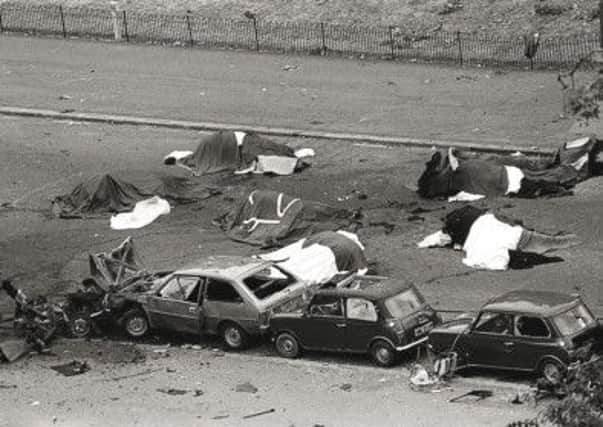

It’s the image of the horses that endures. Seven black carcasses strewn across South Carriage Drive, transforming a street usually thronged with tourists into an al fresco abattoir. But the human cost of the Hyde Park bombing on 20 July 1982, was enormous: four members of the Royal Household Cavalry, Blues and Royals, two of them newly-weds, died as they made their way to Buckingham Palace for the Changing of the Guard, their lives sacrificed to a cause of which they knew little, while 31 other people were injured.

And then there was Sergeant Michael Pedersen; he and his horse Sefton recovered from their injuries and went on to become minor celebrities. Thirty years later, and a month after he told his doctor he was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, he killed his two children and himself as his marriage imploded. Perhaps there was no link between the two acts of savagery, but the pain caused by this atrocity and others like it has trickled down through the years, leaving a trail of bitterness and casting a shadow over efforts to bring lasting peace to Northern Ireland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor the relatives of the soldiers – Lieutenant Anthony Daly, Trooper Simon Tipper, Lance Corporal Jeffrey Young and squadron quartermaster Corporal Roy Bright – the trial of John Downey, whose fingerprints were allegedly found on the parking ticket on the blue Morris Marina containing the nail bomb, offered the opportunity to lay some of that bitterness to rest. So the news last week that a letter sent to Downey, 62, and 186 other so-called “On The Runs” meant he could not be prosecuted came as a devastating blow.

Worse was the knowledge that Downey had received the letter assuring him he was not being sought in connection with any crime in error. A failure of communication meant the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) was unaware the Met still had him in its sights. Though the PSNI later realised its mistake, no effort was made to correct it.

In the wake of Mr Justice Sweeney’s judgment last week, which found the public interest in prosecuting someone for mass murder on the streets of London was “very significantly outweighed” by the public interest in “holding officials of the state to promises they had made”, and the subsequent collapse of the case at the Old Bailey, the soldiers’ families said they would live the rest of their lives in torment as a result of the blunder and in the knowledge that justice was unlikely ever to be done.

Their sense of betrayal was no doubt compounded by plans for a party at Downey’s local restaurant in Donegal to celebrate his homecoming.

Last night the event was cancelled, and Downey issued a statement saying he would “never try to insult or add to the hurt of anybody who is bereaved as I am only too aware of their pain as there are many bereaved families also in the republican community”.

He added: “I refuse to allow what was planned as a simple get-together of family, friends and neighbours who supported me throughout my wrongful arrest and imprisonment in England to welcome me home and allow me to thank them, to be misrepresented and turned into a media circus.”

But the potential repercussions of the letters sent to Downey and others – the product, it is claimed, of a side deal agreed behind the backs of Northern Ireland’s First Minister Peter Robinson and Justice Minister David Ford – will not be so easily erased. The idea that Republican “On The Runs” may have been granted a de facto amnesty not extended to, for example, the soldiers implicated in the Bloody Sunday killings, is anathema to many hardline Loyalists and feeds into a festering, if hard to justify, sense that unionists got the scrag-end of the peace deal. And though David Cameron’s announcement of a judicial review has staved off Robinson’s threatened resignation and the collapse of Stormont at least until after the council and European elections in May, dealing with the issue of the “On The Runs”, whose fate was linked to the IRA’s decommissioning of weapons, cannot be postponed indefinitely.

Given what was at stake, there are those who view the secret deal as one of the unpalatable but necessary compromises struck in peace processes the world over.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“With hindsight we can forget what an effort it was [to keep the peace process on track]. There were a series of fudges, a lot of things were done without it being said that they were being done and there was a kind of broad political acceptance at the highest level that this was happening,” says Peter Geoghegan, editor of Political Insight magazine. The letters, he suggests, were one way to help Sinn Fein sell the peace process to hardliners and prevent them joining dissident groups.

But others, including Jonathan Tonge, professor of British and Irish politics at Liverpool University, believe the lack of a popular or political mandate for the deal means the British government has some explaining to do. And then there are a handful of observers for whom the clandestine nature of the agreement is evidence that there were no depths to which Tony Blair’s administration would not stoop to secure a famous victory and a lasting settlement.

Whatever, the letters and the furore they have sparked are a reminder of the fragility of peace in Northern Ireland, while the judicial review, ordered in defiance of the Attorney-General, highlights the piecemeal approach taken to tackling the province’s residual problems.

Just over a year after Loyalists took to the streets over the decision to limit the flying of the Union flag over Belfast City Hall, and a few weeks after the humiliating failure of the Haass talks to resolve this and other outstanding issues, the province is yet again teetering on the brink of a crisis. The latest furore has raised many questions: Do the letters grant blanket immunity to all 187 “On The Runs” who received them? (The judge’s ruling suggests yes, but Northern Ireland Secretary Theresa Villiers says no). And was Robinson really unaware a deal had taken place? (Sinn Fein’s Martin McGuinness says the Northern Ireland policing board, which includes members of Robinson’s Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), was briefed on elements of the scheme, albeit without mention of the letters).

But the over-arching riddle is the one Northern Ireland has struggled to solve for many years: unless it can come up with an effective framework for dealing with its past, how can it possibly move on?

The problem of what to do about the “On The Runs” proved a sticking point from the earliest stages of the peace process. The Good Friday agreement allowed hundreds of Republican and Loyalist prisoners to be released early on licence, but left the issue of those suspected of – but never charged with – terrorist offences unresolved. In part this was because, while prisoner releases affected both sides of the sectarian divide in equal measure, virtually all the “On The Runs” were Republicans, as the Loyalists didn’t have access to boltholes across the border.

It was Sinn Fein, however, that put the kibosh on plans for legislation which would have allowed those accused of terrorist offences committed before 10 April 1998 to appear before a special tribunal and to be freed on licence if convicted. They rejected it because it would also have applied to police officers, soldiers and anyone accused of collusion.

After the legislation was abandoned, Blair told Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams he remained committed to finding a solution and within the year the PSNI had embarked on Operation Rapid, the codename for a review of people identified by Sinn Fein as fugitives or “On The Runs”. The review examined what basis, if any, the PSNI had to seek their arrest, and those who were unlikely to be prosecuted were sent the letters which made it possible for them to return to the UK.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThough the deal was struck under Labour, 38 of the letters have gone out since the Tory/Liberal Democrat coalition came to power in 2010. Robinson has claimed some of the “On The Runs” were given Royal Prerogatives or pardons. And on Friday, unionists called on the Northern Ireland Office to stop considering five more active cases.

The collapse of Downey’s trial left the DUP’s high command looking foolish and facing criticism from hardliners: hence Robinson’s threat to resign. The judicial review combined with Villiers’ pledge that other “On The Runs” will be warned their letters cannot be used to avoid questioning, has eased the pressure, but it is a short-term fix. As the inquiry’s remit is likely to be limited to the way in which the scheme was administered – questions over its wider legitimacy are unlikely to be addressed.

The lack of any transparency has made unionists suspicious other side deals may have been struck. It is also possible, Tonge says, that the DUP will now push for a full list of “On The Runs” and that people suspected of highly emotive crimes such as the Enniskillen bombing and/or senior figures within the Republican movement might be on it. At the same time, any move to rescind or dilute the protection offered by the letters could lead to Sinn Fein’s leadership being placed under the same kind of pressure Robinson has faced in recent days.

The most pressing problem with the judicial review, however, is that it represents an ad hoc approach to an enduring problem: how Northern Ireland deals with its past, and particularly with the 3,000-plus murders that remain unsolved. The existing body set up to investigate cold cases – the PSNI’s Historical Enquiries Team (HET) – has been widely derided for its failure to deliver and yet there seems to be an almost perverse resistance to adopting any alternative mechanism.

Aspects of the peace deal have made evidence-gathering more difficult. Under the terms of the Good Friday agreement, weapons which have been handed over cannot be forensically tested, nor can information leading to the discovery of the “Disappeared” be used as evidence in a criminal case.

“More than 15 years have passed since the Belfast Agreement, and there have been very few prosecutions, and every competent criminal lawyer will tell you the prospects of conviction diminish, perhaps exponentially, with each passing year,” said Northern Ireland’s Attorney-General John Larkin last year. Nevertheless his suggestion that a line should be drawn under prosecutions was met with outrage from victims’ support groups and Amnesty International. This is despite the fact the PSNI Chief Constable Matt Baggott has said the cost of policing the past has a massive impact on how the force deals with the present and future.

Calls for a Truth and Reconciliation Commission like the one in South Africa have met with similar opposition. Even attempts by US negotiator Richard Haass, to bring in a new, more independent version of the HET, called the Historical Investigations Unit, with powers to compel witnesses to give evidence and grant limited immunity, eventually foundered.

Indeed the sheer intractability of Northern Ireland’s problems could be seen in the failure of the Haass talks – which lasted six months and cost £250,000 – to secure agreement on any of the main issues it was set up to resolve. Geoghegan believes the moment for a Truth and Reconciliation Commission may already have passed. But as the relatives of the dead soldiers try to reconcile themselves to their disappointment, the only other option seems to be perpetual firefighting, or worse.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTonge says the reluctance to institute a Truth and Reconciliation Commission has led to the kind of “whataboutery” witnessed last week, where if Republicans are perceived to have been given a Get Out of Jail free card, then the unionists say: “What about the British soldiers?” and vice versa.

“The failure to deal with the past has been one of the most debilitating and destabilising aspects of the peace process, because people are still fighting the war by proxy,” says Tonge.

The fear is that the new inquiry, already perceived in some quarters as kowtowing to the DUP, will make matters worse. “Are we going to end up in a situation where we have ad hoc judicial reviews every time there’s a crisis?” Geoghegan asks. “I think this is very worrying approach to the past in Northern Ireland. It’s unlikely to provide satisfactory answers and it’s unlikely to provide satisfactory justice.”

Twitter: @DaniGaravelli1