Dani Garavelli: Operation Bergen-Belsen

MAJOR-General James Johnston was commanding the 32nd Casualty Clearing Station, a mobile field unit equipped to deal with 200 patients near the German-Dutch frontier, when on 17 April, 1945, he was ordered to move his unit south and take charge of the sick and starving at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, which had just been liberated by the British Army.

The Scottish doctor – a cheerful, unruffled man, who studied medicine at Glasgow University – was no wide-eyed innocent. At 34, he had already played a key role in the relief operation after the earthquake in Quetta which killed 30,000 people; he had been awarded the Military Cross for rescuing a wounded officer under fire in Waziristan; and he had taken part in the D-Day landings. But nothing could prepare him for the horror he was about to encounter nor for the scale of the challenge that lay ahead as – obscenely under-resourced – he fought to contain the outbreak of typhus sweeping the camp and oversee the treatment of tens of thousands of desperately ill patients.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLike many men of his time, Johnston didn’t talk much about his time as senior medical officer at Belsen in later years, but he did compose an account now stored in the Holocaust Museum in Washington. “Little did I know that I was about to be faced with the greatest test of my career, with a situation that would remain engraved on my memory for the rest of my days and would instil in me a lasting abhorrence not only of those who had perpetrated this crime on humanity, but also of those who had condoned it,” he wrote.

Unlike Auschwitz-Birkenau, the extermination camp where more than a million Jews died, Bergen-Belsen, near Celle, was not designed as a killing machine (there were no gas chambers, though internees were abused); rather it was intended as a holding station for Jews who were to be exchanged for German prisoners of war. But as German defeat began to look inevitable and the Russians moved west, many thousands – including Anne Frank – were brought on death marches from other camps, until Bergen-Belsen could no longer cope with the numbers.

By mid-April 1945, all semblance of order had collapsed. Typhus – caused by body lice – was rampant, there was no food or water (partly as a result of Allied bombing) and the huts were so overcrowded, those inmates who still had the strength to move couldn’t do so without stepping on others. Diarrhoea was widespread and ran unchecked on hut floors. And with the living too weak to bury the dead, 13,000 corpses lay piled up three or four feet high close to the accommodation blocks.

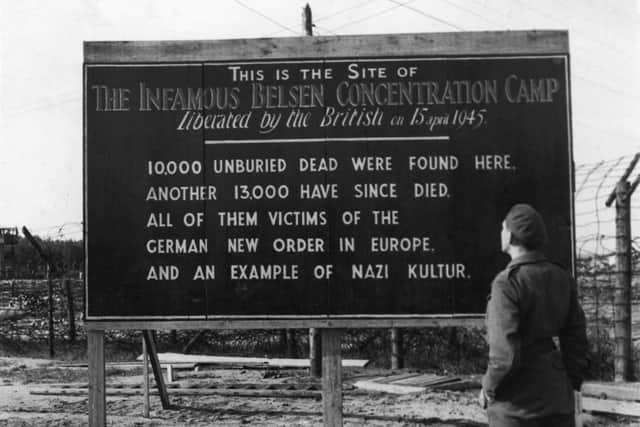

So appalling was the scene that greeted the British 11th Armoured Division when it arrived on 15 April, those who saw it struggled to describe it and those who were told about it struggled to believe it, even when images began to filter into the public domain. Later, Johnston expressed his outrage at having heard a woman view footage and say: “Those bodies must have been put like that for the picture.”

BBC journalist Richard Dimbleby was one of the few who came close to capturing the suffering inflicted on the Jews and other prisoners: “The living lay with their heads against the corpses and around them moved the awful, ghostly procession of emaciated, aimless people, with nothing to do and with no hope of life, unable to move out of your way, unable to look at the terrible sights around them,” he reported.

A common theme among witnesses was that the wasted figures inside the camps had been so stripped of their humanity that it was difficult to relate to them as individuals. The challenge Johnston and his colleagues faced was not only to save lives but to restore the survivors’ sense of self. The degree to which they were successful has been debated ever since. Some 14,000 people died in the weeks after liberation. Critics argue the British Army’s ill-preparedness and its “inertia” when it came to providing resources was evidence of its indifference, others that the scale of the task made a speedier response impossible. But few would dispute that those involved at ground level worked heroically in the most daunting of circumstances.

Next month, the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Belsen will be marked with a ceremony at the site, which – like Auschwitz – stands as a reminder of man’s capacity for evil. But man’s capacity for good is also remarkable. And, arguably, it shone through in the efforts of individuals such as Johnston, who attempted to turn darkness into light.

By the time Johnston arrived at Bergen-Belsen, the 11th Armoured Division had been in place for several days. The camp’s liberation had been secured by means of a truce and an exclusion zone to prevent the spread of disease. After British troops entered, Commandant Josef Kramer was arrested and many Germans sent back to their lines, but some German and Hungarian SS officers remained to help prevent internees from escaping. The Hungarians were also ordered to bury the dead, at first by hand and, when that proved too slow, by bulldozer, with 26,000 bodies placed in mass graves in the two months after liberation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBelsen was split into two distinct sections. The internees in Camp One – the “horror camp” – were, in Johnston’s words, “emaciated, apathetic scarecrows huddled together in wooden huts”. There was no sanitation and almost everyone was ill. “The smell inside these huts was indescribable. When we started to work in them, we found it difficult to do so for more than ten minutes or so at a time without feeling physically sick,” he wrote. In Camp Two, conditions were slightly better. Its 15,000 male internees had arrived more recently and, though malnourished, were in better health.

With just a handful of doctors, sisters and orderlies at his disposal, and the majority of internees requiring hospitalisation, Johnston’s job must have seemed overwhelming. Sending soldiers out into the countryside to find supplies and equipment, he drew up a list of priorities: to feed everyone, to prevent the spread of typhus and to transfer internees from the horror camp to a hospital or other accommodation.

The simple act of feeding people was a nightmare; most were too weak to digest solid food, though they wanted it, and sometimes fought for it, and finding anything their systems could process without becoming ill was problematic. To begin with, fitter internees were asked to distribute milk, but ensuring everyone actually got some was nigh on impossible and the most malnourished couldn’t assimilate the fat in the tinned full milk so it had to be diluted.

Nor would getting internees out of Camp One prove any easier. Johnston commandeered a former Panzer training establishment which – once adapted – could accommodate 10,000 patients, but the transfer was hampered by the lack of resources and by the need to delouse everyone from Camp One.

At first, Johnston thought it might be possible to draw on the expertise of the 200 internees who were doctors or nurses, but most were too fragile and too traumatised to help. Two exceptions were Dr Hadassah Bimko and Dr Ruth Gutman, strong women Johnston described as “the personification of good over evil”. Despite suffering great personal losses, they had managed to run a small “hospital” in one part of the female section and their skills and fortitude were indispensable to Johnston and his team.

In time, more help arrived; the small number of doctors and nurses were supplemented first by the 11th Light Field Ambulance and then by six detachments of British Red Cross workers. Later, 35 German medical officers, 130 nurses and 140 male orderlies were sent from PoW camps, along with 100 British medical students.

The decision to bring in German PoWs was resented by the internees, some of whom sought revenge, but Johnston knew it was necessary. When they proved uncooperative, failing to turn up for parade on their first day, he summoned their senior officer and told him he’d be hanged from a nearby tree if they did not appear as ordered within the hour. There was little open defiance after that.

Some of the German nurses were put to work in the “human laundry”, a former stable block where internees from Camp One were scrubbed, shaved and sprayed with the insecticide DDT in preparation for transfer to hospital. The thought of fragile patients being manhandled on hard slabs by enemy nurses seems barbaric, but there was little alternative.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy the night of 19 April, the hospital was ready to receive its first patients, but – in a final act of sabotage – departing German soldiers cut off the water supply, delaying the start of the operation by more than 24 hours.

By 23 April, the transfer of “fit” internees from Camp One to Camp Two had not begun. Still, as staffing levels rose, the number of deaths began to fall, from 500 a day in April to 60 a day by mid-May.

So much of what went on in the weeks after liberation was bleak, but there were moments of hope too. One day, a consignment of lipsticks arrived at the camp. The army officers were annoyed: why had anyone sent something as frivolous as make-up? However when they saw emaciated women, wrapped in a blanket, but with scarlet lips, they realised the lipsticks had reminded them they were more than a number and restored some of their self-esteem.

Another watershed moment came when the recovering internees, many of them talented musicians, began to stage concerts, which helped the soldiers to see them not as degraded victims, but as the individuals they had once been. “I think a lot of people didn’t make that leap; they thought this is all bestial and like a zoo. [The concerts] were important because they prompted a kind of moral reawakening,” says Ben Shephard, author of After Daybreak: The Liberation Of Belsen.

Between 21 April and 18 May, a total of 13,834 patients were evacuated from the horror camp. It was decided it should be burned and, on 21 May, the last hut was destroyed, with speeches and great fanfare. Johnston was one of four Army officers to fire a flame-thrower from a Bren gun carrier at the building.

After the immediate medical crisis was over, the Belsen survivors became part of the wider problem of the 10 million or so displaced persons in Germany. Some Jews went back to their home countries, others wanted to go to Palestine. As people flooded in from elsewhere, the barracks became the biggest displaced persons’ camp in Europe. Around 2,000 babies were born there before it closed in 1950. As for the Belsen guards, 45 of them were tried by a military tribunal. Eleven, including Kramer, were sentenced to death.

In his book, Shephard explores the criticisms levelled at the British Army and agrees there were flaws in the relief operation. In particular, he says, medical researchers drafted in to help with the feeding were so convinced hydrolysates – experimental proteins – were the answer to malnutrition that they continued to force them on patients after it should have been clear they were not working. Also, there were three types of soldier at Belsen – medical, military government and garrison – so Johnston shared hands-on authority with two other senior officers, and all three operated under the command of Brigadier Glyn Hughes, deputy director of medical services of the 2nd Army. Shephard points out that this lack of a clear chain of command was the cause of some of the delays. Still, the historian concludes Johnston was an effective leader.

“He is described as having a glint in his eye and a burr in his voice; he was charming and flexible, willing to change course when it became clear something wouldn’t work,” says Shephard, “but – as with the uppity German officer – he could be absolutely ruthless when necessary.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohnston, who left school at 15 and spent a year as a farm apprentice on Arran before deciding to train as a doctor, was awarded the OBE for his work at Belsen and promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. He continued serving in the Army – in Malaya, Cyprus and Germany, as well as England – until 1970. He and his wife Enid retired to the village of Northiam, east Sussex, where he died in 1988.

At her home in Kent, his daughter Cara Kelly remembers him as a modest man who rarely talked about his achievements. “He wasn’t your archetypal Army type – he was humble and unpretentious. He wouldn’t throw his weight around. He was a compassionate and sensitive man, a good listener who was always helping the people in his life,” she says.

After the war, Johnston kept in touch with Dr Bimko, who went on to marry fellow internee Josef Rosencraft, meeting up with them when they came to England in 1965. Ten years later, he was contacted by Dr Gutman. She told him she had returned alone to the small town on the Austro-Yugoslav border where she had lived before the war. Around a week later, she saw a figure walking up the road; it was her husband, released from his own internment. She had not known he was alive.

After the burning of Camp One, few traces of Bergen-Belsen remained, but gradually former prisoners put up their own monuments. A permanent memorial was opened in 1952 and a documentation centre in 2007. Today, 300,000 people a year visit the site.

Johnston returned to Belsen several times; on one occasion, in 1969, he saw busloads of German schoolchildren being shown around. Addressing suggestions it should be shut down, he wrote: “Belsen and the other concentration camps should never be forgotten, not only because they are memorials, but also because they act as a reminder of the incredible bestiality and cruelty which happened once ‘in this enlightened age’ and must never be permitted to happen again.”

Given the atrocities committed since – in Kosovo, Rwanda and Darfur – it seems foolhardy to suggest we have learned from the past. But next month, survivors and their families will join German president Joachim Gauck at the site. And they will remember. «

Twitter: @DaniGaravelli1