Dani Garavelli: Lessons from the fall of Flowers

Of course, we know from bitter experience that those who present themselves as the social conscience of an organisation can get away with almost anything. Isn’t that how Jimmy Savile did it? By backing the right causes, by raising millions for hospitals, he was able to roam the country picking off vulnerable children at will. Those who guessed at his vices turned a blind eye, because no-one was willing to challenge his elevated status. Hiding in plain sight, as the Yewtree officers put it.

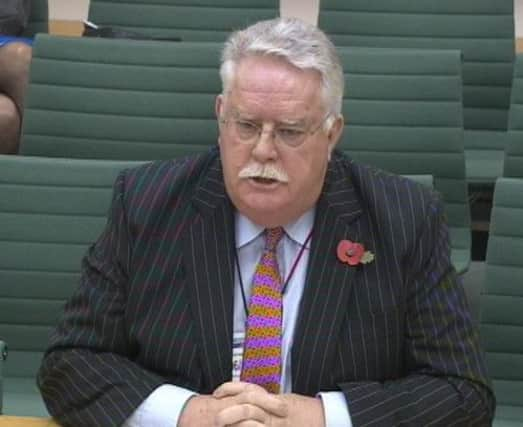

That seems to be what Flowers, in his own way, did too. Everyone seems to have been aware of his weaknesses. His predilection for gay porn cost him his position as a councillor in Bradford (though he was allowed to resign and avoid disgrace) and his alleged drugs habit seems to have been the talk of the steamie. One MP is supposed to have made a joke about his having “a touch of the old Colombian flu” around the time of his appearance before the Treasury Select Committee hearing into the Co-operative Bank’s problems when he underestimated its assets to the tune of £44 billion.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe had next to no qualifications for the role of chairman and had already left at least two organisations under a cloud: Bradford City Council and the Manchester-based drugs charity Lifeline where, as chair of the board of trustees, he was investigated over his expenses in 2004. Yet his reputation was untarnished and his career trajectory unaffected. Some have suggested his rise was the result of cronyism, with Flowers protected by his position in Labour’s cosy elite; others have pointed to the Co-op’s generous loans and donations to Labour as evidence of a symbiotic relationship which laid both parties open to potential corruption. But Flowers’ story is also about how he played to the sensibilities of those around him.

Long before he wrote Capturing the Ethical Opportunity, a document which set out the Co-operative Group’s efforts to promote healthy eating, launch a green schools education programme and provide bank accounts for prisoners, Flowers appealed to those for whom equality and human rights is more than just a gimmick to help their company stand out in a crowded market.

For a start he was an openly gay minister at a time when homosexuals were mostly in the closet. And so what if he was convicted of gross indecency in a public toilet in 1981? Back then there weren’t many places gay men could meet for sex. It happened all the time.

If the Methodist Church chose to overlook this misdemeanour then it was only living up to those values it espoused: forgiveness and a belief in second chances. The same could be said of the gay porn. The material Flowers was accessing was not illegal. He shouldn’t have been looking at it on council computers, but did he really deserve to lose his standing within the Co-op as a result? It is easy to see how one might sympathise with a man whose experiences of homophobia led him to the occasional lapse of judgment, especially since, until the mid-noughties, he seems to have been genuinely on the side of the poor and dispossessed, welcoming asylum seekers to his church. Of course, there came a point – quite some time ago, it would appear – when it began to become clear that Flowers was not so much struggling with his demons as egging them on.

How much anyone knew about his supposed drug-fuelled orgies is unclear, but his behaviour was erratic enough that it should have sounded alarm bells, particularly when combined with his lack of relevant qualifications. By then, however, he had worked his way up through the Co-op – from area committee to regional board to national board. Being an ideological company, it seems it favoured his political credentials over other people’s financial ones, and so he got the job of chairman.

The apparent lack of effective monitoring has been just as damaging for the Co-operative as for other less ethical banks, even if it was driven by different pressures. Now, an institution with a reputation for integrity has a £1.5 billion capital shortfall and is being bailed out by hedge funds. Those long-standing customers who put their faith in Co-op’s higher standards, and those who transferred their accounts there after the greed and recklessness of other banks were exposed, have been betrayed.

The temptation may be for them to once again seek out alternatives, but Ethical Consumer magazine has recommended they stay put in the short term so they can exercise a degree of control while the mess is sorted out. Flowers, 63, who was arrested and then bailed last week, has blamed any wrong-doing on the stress of losing his mother.

An independent inquiry into exactly what went wrong at the Co-operative Bank has been ordered, but some lessons are already obvious. Though looking for the best in people is to be commended, it can sometimes lead to the worst being ignored, allowing the unscrupulous to take advantage. And even the most high-minded and ethical of institutions needs gimlet-eyed scrutiny and financial expertise to keep it on the straight and narrow. «

Twitter: @DaniGaravelli1