Covid pandemic: Vaccines are the way out of this crisis but only if we take them and rich countries help poor ones – Susan Dalgety

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

If it had not been for the expert eye of a nervous, yet determined, junior doctor, she may well have died from a deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

“She’s too young for a DVT,” said the medic, “but I am going to admit her…just in case.” She saved her life, and the investigations that followed revealed that our family had a genetic thrombophilia condition – anti-thrombin 3 deficiency. In layman’s terms, our blood clots up to eight times more than normal, making everyday activities, such as flying, the contraceptive pill and sitting for more than 90 minutes, dangerous.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJust how dangerous was brought home to me two years after my niece’s brush with death, when my healthy 30-year-old son collapsed with a pulmonary embolism (PE). Once a PE is diagnosed, there is nothing anyone can do except hope that medication disperses the clots before they reach your heart or brain, where they will kill you. It was a long couple of days.

My sister, brother and his eldest daughter have the condition. My mother does too, and her father was found dead in bed at only 60, from a coronary thrombosis. Recently, when researching our family tree, I found the death certificate of his sister, my great aunt, Alice O’Hare, who died aged 30 in a New York hospital while giving birth. A pulmonary embolism was the cause of her death.

‘Should I get it?’

And I have it, which is catnip for a hypochondriac like me. Every twitch in my leg is a clot, every headache is a clot, every chest infection is a clot. So, when it was revealed that fatal blood clots were one of the nasty side effects of Covid-19, I panicked, convinced that if I did get the virus I would die of a stroke.

My relief at the prospect of a vaccination before Easter was palpable. Then the first news stories of a possible link between the Oxford-AstraZeneca shot and blood clots trickled out. “Should I get it?” asked my son, who qualified for one because of his underlying condition.

“Of course,” I said. “The risk is far less than if you caught Covid.” And I pointed to his grandmother who had just had her second AstraZeneca jag and was as sprightly as ever. “And your auntie is fine too, she had hers a week ago,” I added for extra reassurance.

Three weeks later and we have both had our first shots. The side-effects have worn off and I am looking forward to my second one, and the faint prospect that I will be able to travel to France later in the year.

Failing that, I can’t wait to have a long, boozy lunch in my favourite French restaurant in Edinburgh. I occasionally panic at the thought of a vaccine-related clot – I am a hypochondriac after all – but not enough to stop me from topping up my Oxford-AstraZeneca when the time comes.

And I was delighted to read a YouGov poll yesterday that shows that most Britons trust the vaccine. There are far more dangerous things in life: pregnancy puts women at five times more risk of developing a clot; the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) suggest that chances of getting a DVT on a flight of more than four hours is one in 4,600; and for women on the pill, the risk is one in 1,000. The risk of getting a clot after an Oxford-AstraZeneca jab is one in 250,000, or 0.0004 per cent. Even I can do the maths.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad‘Enlightened self-interest’

A far bigger risk to everyone’s health is if rich countries don’t ensure that the world has access to a vaccine, whether it be the Oxford-AstraZeneca dose, the one-shot Johnson & Johnson or even Russia’s Sputnik V.

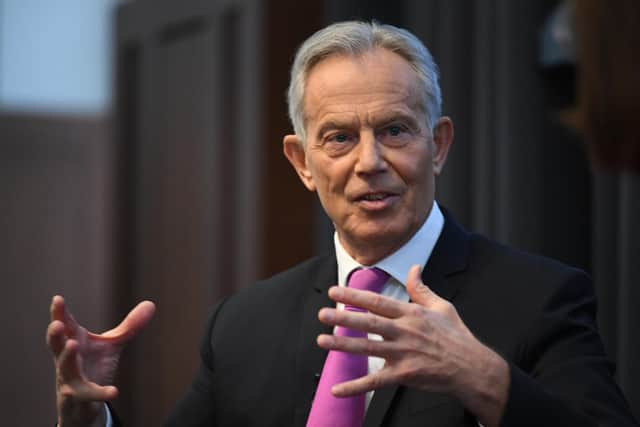

As Tony Blair whose Institute for Global Change now focuses on the Covid crisis, warned earlier this week, “Covid anywhere is potentially Covid everywhere.”

He pointed out that there is a big disparity in the how the world is dealing with the pandemic. “Africa is without substantial amounts of vaccine and struggling – at least in the first half of the year – to get that vaccine and yet the rest of the world… will have more vaccines than individual countries need.”

I have friends in Malawi who have had their first Oxford-AstraZeneca shot, but the world’s current plans will not be nearly enough to stop the spread of the pandemic. The Covax programme, which most countries on the continent have signed up to, aims to supply 600 million doses to Africa, enough for 20 per cent of the population. But scientists say that the vaccination rate of any country needs to be as high as 70 per cent if there is to be any hope of herd immunity.

“We need a much more rounded, enlightened self-interest approach from the countries manufacturing vaccines,” urges Blair. “… It has got to be speeded up. I personally would like to see the situation where, at the end of this year, Africa is substantially vaccinated.”

When news started to filter through from a distant city in central China of an outbreak of “pneumonia” linked to the local seafood market on December 31 2019, few of us took any notice.

Fifteen months later our lives, and the world, have been turned upside down by the novel coronavirus that emerged from Wuhan. We will get through this pandemic, but only if we each get vaccinated, and only if rich nations help low-income countries with supplies and support to manufacture the vaccine themselves. If the pandemic has taught us anything, it is that we are all better together.

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.