Could the Scottish gaming industry be doing more?

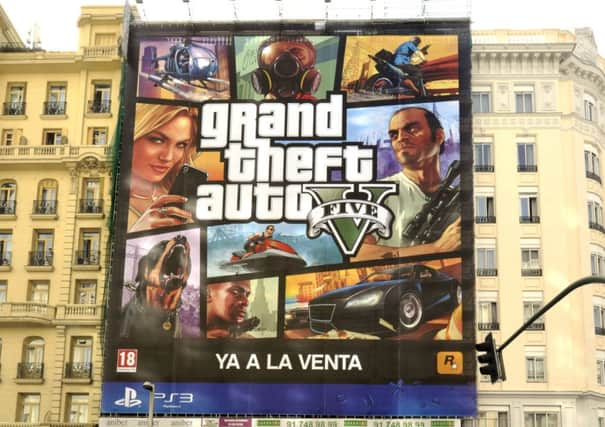

The success of Rockstar North can make your head spin. When the Scottish games company launched Grand Theft Auto 5 last year, it made almost £512 million in one day.

For the next month the game outsold the entire global music industry, breaking seven Guinness World Records.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn the one hand, Grand Theft Auto is an anomaly – a hit for two decades in a global industry that changes so fast and so often that even the most expert observers are constantly caught by surprise. On the other hand, the figures above merely reflect the fact that gaming is now the most popular, and arguably the most significant, art form in the world.

“When games are successful they’re massively successful,” says Brian Baglow, who worked on the first Grand Theft Auto and is now director of the Scottish Games Network, a national umbrella organisation which acts as “a focal point and community”.

“Games can soak up more time from people than anything else. Doctor Who takes up an hour. Grand Theft Auto gives you hundreds of hours of game play. You can be playing for months, if not years.”

Another factor, Baglow points out, is ease of distribution. “The film sector in the UK is hamstrung by distribution, but two guys in a bedroom in Dundee can build a game and get it seen by a global audience. If it’s getting lots of downloads in Russia they can get it translated. The tools are there to get it out into a global marketplace in a way that’s never been done before.”

It’s a success documented in Game Masters, the National Museum of Scotland’s second major exhibition devoted to the gaming industry (after Game On, a decade ago), in which Baglow’s sketches for GTA sit alongside everything from 1980s arcade games to a SingStar booth.

The show was created by ACMI (Australian Centre for the Moving Image) in Melbourne. NMS is the first venue in Europe to host it. “It’s a natural fit,” says Ben Cram, ACMI’s exhibitions co-ordinator. “I lost a summer back when I was a wee child to Lemmings. Or invested it. It wasn’t like anything else I’d ever seen.”

Lemmings, created by Dundee’s DMA Design, (which later became Rockstar North), made Grand Theft Auto possible. “It gave DMA significant commercial credibility,” Baglow recalls, “and allowed them to decide what projects they wanted to do.”

DMA’s early success also laid the foundations for a gaming industry in Scotland that consisted of only six companies in the 1990s but now boasts almost 100 – three of which, Lucky Frame, Space Budgie and the Story Mechanics, also feature in Game Masters, in a new Scottish section assembled by NMS curator Sarah Rothwell. The intention, she says, was to showcase “the Scottish game-makers who are pushing the boundaries of what is considered as gaming. Dundee is the main centre of development but there are many companies branching up in Edinburgh and Glasgow as well.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf this paints a rosy picture of Scotland’s gaming industry, the reality is more complicated. “I don’t feel there is much creativity going on in Scotland,” says Yann Seznec of Lucky Frame, who moved to Edinburgh from Pittsburgh to study and stayed to set up the company. “Working here is wonderful because it’s a small community and costs are much lower than in most of England, which gives us the opportunity to make really experimental and off-the-map work, but I haven’t really seen much of that, with some notable exceptions from people like Michael Brough or Quartic Llama.”

Grand Theft Auto aside, Scotland isn’t as commercially successful as it could be either. “In my experience people are pretty unaware of the Scottish development scene,” adds Seznec. “That’s not terribly surprising, considering that the population is roughly equivalent to Finland, with a fraction of the output.”

Baglow agrees. “Finnish companies are pulling in venture capital like you wouldn’t believe. Scotland’s game sector is incredibly active, but it’s getting harder and harder to make an impact simply because there’s so much competition. There are 1.6 million apps on the app store and billions of players worldwide. Economically and culturally, we’re not doing as well as we could be. When you look at our output last year, 20 per cent was quiz and puzzle titles, about 16 per cent was kids’ titles. I don’t think we’re really pushing the boundaries.” Baglow’s response is to “change Scottish Games Network into something more proactive” to encourage innovation.

And there are plenty of boundaries still to be pushed, Rothwell suggests. “Guerrilla Tea, also based in Dundee, are working with Cancer Research. Space Budgie create art-based empathy games – 9.03m was based around the Japanese tsunami and gets you to think about the aftermath of that.” She also mentions Quartic Llama, admired by Seznec. “Other, which they developed last year with the National Theatre of Scotland, was part performance art piece, part horror movie, part interactive game.”

Indeed, while Baglow hopes Game Masters will help persuade more people “that you can’t just write it off as toys for silly grown ups”, the question of whether gaming is art feels more redundant than ever. In fact, there is almost no area of culture that gaming hasn’t influenced in some way, from theatre (think of Tim Etchells, Punchdrunk and Blast Theory) to pop music (Björk and the Black Eyed Peas, among others, creating interactive albums) and cinema, which, having stumbled for years in its attempts to adapt games to the big screen, finally seems to have captured the gaming experience in movies like Edge of Tomorrow and Scott Pilgrim Vs The World.

For Baglow, something of an evangelist for gaming, it goes far beyond that – gaming, as a way of looking at the world, has the potential to re-shape our entire lives. “All these new devices open all sorts of new opportunities to play. Your journey to work can be more of a game – if you’re using public transport you get bonus points for not using your car. We could create entirely new experiences that bring together all different kinds of media in a way that is artistic in the context of healthcare or education.” Rothwell agrees. “With the advent of mobile technology we’re taking games with us all the time. It’s part of everybody’s lives now.”

Baglow talks enthusiastically of “empowering people to build their own universe”. There is a counter-argument – probably best saved for another day – that this ‘power’ is an illusion, gaming culture’s exhilarating rise coinciding, as it does, with a frightening rise in corporate power and surveillance culture (enabled, in part, by all this new interactive technology). What isn’t in doubt is gaming’s extraordinary cultural reach. So how does Scotland continue to have a stake in it? “I don’t know,” say Baglow. “If I did I’d be over in San Francisco making a fortune.” He reels off examples of gaming’s unpredictability – Rovio, creator of Angry Birds, laying off 130 staff last month and, by contrast, the unexpected success of Minecraft among children. “Nobody saw that coming,” he marvels. “Where we are in five years is one of the questions that always tends to come up. And nobody knows.”

• Game Masters, National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh, until 20 April. www.nms.ac.uk