Climate change: Scotland's green housing revolution has a fundamental problem – Martyn McLaughlin

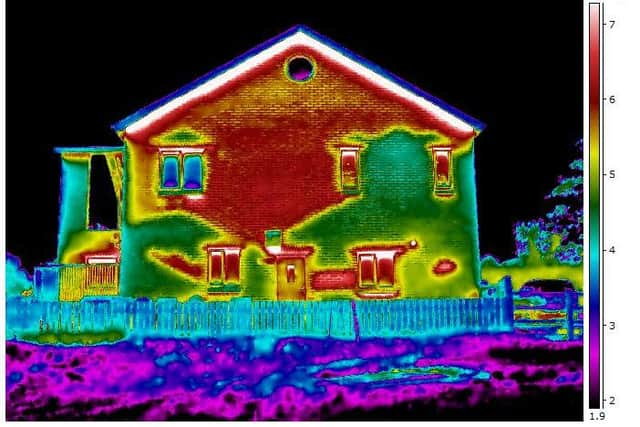

The resultant story asked questions about how, in the year Cop26 is coming to Glasgow, we are doing such a poor job when it comes to curbing emissions from our buildings.

The focus of my research was non-domestic properties, in particular those venues which will host world leaders during November’s summit, but the challenge is no less acute when it comes to our homes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAddressing this will be a major determinant of whether the nation can meet its ambitious climate change targets, and with the right policies and adequate investment, it can help create a thriving green mini-industry via the rollout of low-carbon heat networks and a major uptake in the use of heat pumps.

The obstacles to progress are plentiful and, unsurprisingly, cost is among them. The bill for purchasing and installing a heat pump in a property can run to several thousand pounds. For most families, the upfront fees are too prohibitive, even though it is one of the biggest carbon savings a household can make – a fact reflected in future energy bills.

The financial hurdle is considerable, but it could be solved by a transformative grant system – one which ensures that going green does not hit people in the pocket. That requires political will as much as deep pockets.

An even graver and obstinate challenge will be enabling a behavioural shift which compels people to engage with the issue and consider how they can reduce their carbon footprint at home.

There is, of course, something of the chicken and egg to this situation, and the two strands are not mutually exclusive; a key part of the charm offensive will be demonstrating how households can save money over the medium to long-term.

Unfortunately, even that inducement will do little to counter the perception of energy efficiency as something that is achingly dull. At a time when the urgency of the climate emergency is focused on global issues such as rising sea levels, deforestation, and the rapid warming of the Arctic, no one particularly wants to talk about loft insulation.

But talk about it we must. As things stand, heat in buildings accounts for around 23 per cent of Scotland' s greenhouse gas emissions, with residential properties emitting around 6.2 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent a year – more than three times the emissions from international aviation and shipping.

While there has been a significant reduction in household emissions over the past three decades, the rate at which they are now decreasing is barely a trickle, with a 1.5 per cent fall between 2018 and 2019, according to the Scottish government’s latest data.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAccelerating that downward trend is crucial in order to meet Scotland’s climate targets, and time is not the luxury it once was; around 50 per cent of the nation’s homes – more than a million households – will need to convert to a zero or low-emissions heating system within the next nine years.

The draft policy programme drawn by the SNP and Scottish Greens also commits to ensuring that all homes achieve at least a C rating in their energy performance certificates (EPC) by 2033.

It is a laudable aim, but I wonder whether it is the best way to measure progress. Over the course of the past few weeks, numerous energy efficiency experts I spoke to have expressed misgivings with the EPC system.

The method by which properties are assessed only gives an approximation of energy use and emissions, and some research has indicated that their assessment of property sizes is so flawed as to produce inaccurate ratings.

Rohinton Emmanuel, professor in sustainable design and construction at Glasgow Caledonian University, told me that EPC gradings had to be taken with a “large pinch of salt”.

“Their unreliability is well known,” he explained. “It is based on a theoretical set of assumptions, theoretical outdoor climate, theoretical occupancy, and theoretical use, and not on actual energy consumption.”

Similar misgivings are held by the Climate Change Committee, an independent group of experts who provide the UK government with advice on the climate crisis.

In December, it cautioned that EPCs are a useful source of basic comparable information, but have “extensive issues”, such as poor quality and low robustness. There is, the committee said, an “urgent need” to reform the system.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis may sound trivial, but it matters. A new regulatory framework for energy efficiency standards is being brought in at a UK and Scotland level. EPCs are at the centre of both. There is even talk of EPC ratings being included by mortgage lenders in their lending criteria. Some major banks, including Natwest and Barclays, already provide such products with preferential rates.

In Scotland, a consultation is underway into reform of the domestic EPC system, but it is tantamount to tinkering around the edges, with new metrics designed to allow homeowners and landlords to better understand the ratings. The consultation is not looking at the quality or accuracy of the EPCs that are generated.

The upshot is that the foundational evidence base for a decades-long plan to improve energy efficiency, one which will cost billions of pounds, could be fundamentally flawed. No one at Holyrood seems overly concerned with these anomalies, in part because, well, it’s energy efficiency, and it’s dull.

But if we are serious about lowering emissions and lifting people out of fuel poverty, is it not worth ensuring that the data is reliable?

A message from the editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers. If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.