Climate change: Potentially catastrophic sea level rise can still be avoided and Scotland could even see it reduced to zero – Dr Matthew D Palmer

How can such seemingly small and inconsequential numbers matter? Because they are relentless, compounded by the passing of time.

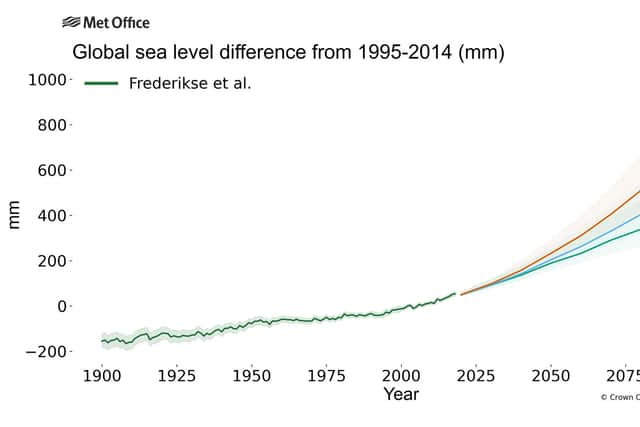

Sea level has risen globally by about 20 centimetres since the start of the 20th century. The equivalent UK average rise is slightly less, at about 16cm. These relatively modest rises are already leading to a real and present danger of increased coastal flooding throughout the world, with low-lying islands and coastal areas particularly at risk.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOver the 20th century, the dominant contributors to global sea level rise were the expansion of the oceans due to warming and the melting of mountain glaciers.

But things are changing. The sea level rise contribution from Earth’s two major ice sheets – Greenland in the north and Antarctica in the south – is now four times larger than during the 1990s. The stability of these vast reservoirs of ice in a warming climate represents an existential threat to coastal communities around the world.

The slow response of the oceans and ice sheets to the warming planet means that centuries of future sea level rise is already “locked in” from past greenhouse gas emissions.

This behaviour is at odds with global surface temperature, which is expected to respond to reductions in greenhouse gas emissions within a few decades.

As assessed in the latest climate change report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the amount of global sea level rise locked in is dependent on the peak future surface warming.

At four degrees Celsius of peak warming relative to a pre-industrial climate, we would see between 12 and 16 metres of global sea level rise over the next 2,000 years.

If peak surface warming is limited to 3C, this range falls to between four and ten metres. If surface warming is limited to the Paris Agreement target of 2C, the range is two to six metres, and two to three metres for 1.5C.

These are big numbers that would present serious challenges to coastal communities around the world. There is also a large degree of uncertainty in how quickly we might reach several metres of sea level rise.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

The speed of future sea level rise depends strongly on the response of the ice sheets. Known ‘fast ice processes’, particularly in Antarctica, could lead to a dramatic acceleration of sea level rise in the coming decades and centuries that follow.

Current scientific knowledge cannot rule out global sea level rise approaching five metres by 2150 and in excess of 15 metres by 2300 under a high greenhouse gas emissions scenario if these fast ice processes are triggered.

However, we know that this risk can be reduced substantially by limiting future warming through reduced greenhouse gases emissions.

What about the UK? In a helpful twist of fate, the relative proximity of the UK to Greenland means that the British Isles will experience almost no sea level rise from the Greenland ice sheet.

As ice is lost, there is a fall in sea level surrounding the ice sheet because the gravitational attraction acting on the ocean is reduced. The UK sits in the “sweet spot” where the local fall almost exactly balances the global rise in sea level from Greenland ice loss.

The main threat for the UK then, comes from Antarctica, which is unfortunately where the most ice and largest uncertainties lie. In addition, ongoing land uplift acts to reduce the rates of sea level rise in the northern UK, while land subsidence exacerbates sea level rise in the south.

The origin of this north-south divide can be traced back to Scotland during the last ice age. The Scottish landscape tells the story of an ancient environment that has been shaped by ice; from the spectacular U-shaped valleys of Strathspey and the western sea lochs, to the high and desolate Rannoch moor, which was once beneath the central dome of the British ice sheet.

The existence of that ice sheet is still making its presence felt in the changing sea levels around Scotland today. The Earth’s crust is still slowly reacting to the loss of ice, resulting in land uplift of up to about 1.5mm per year.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis counteracts sea level rise around the Scottish coast and raises a tantalising possibility; under a future with low greenhouse gas emissions sea level rise could be reduced to zero for much of the Scottish coastline. This possibility represents a rare ray of sunshine in the typically gloomy outlook for climate change.

The science is very clear: the fate of sea level rise, for the UK and the wider world, is dependent on the collective actions of the international community on future greenhouse gas emissions.

If we are able to limit future warming, we can avoid potentially catastrophic future sea level rise that will affect both the UK and countless millions of lives around the world.

For Scotland, there is a very real possibility that future generations could see local sea level rise reduced to zero in the coming centuries if the Paris Agreement’s warming targets are met.

But the window of opportunity to meet these targets is rapidly closing, and all eyes will be on Egypt in early November to see what progress can be made at the COP27 international climate summit.

Dr Matthew D Palmer is the lead scientist for sea level at the Met Office Hadley Centre and an associate professor at the University of Bristol

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.