Cancel culture that ditches To Kill A Mockingbird and dismisses David Livingstone as just another colonialist is lazy and dangerous – Susan Dalgety

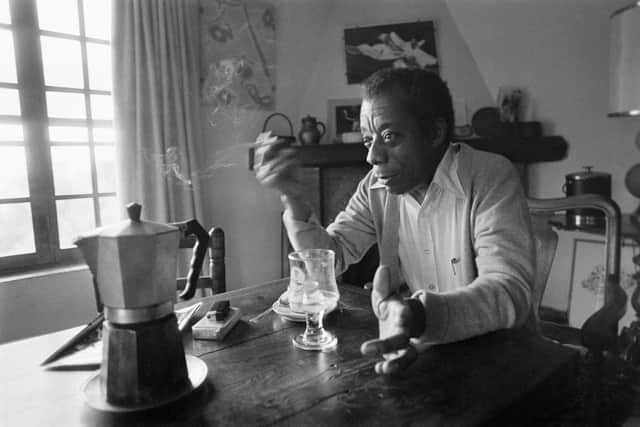

A derivative of the word is now entrenched in urban slang, on both sides of the Atlantic. A more imaginative approach to teaching English literature may have been to use Harper Lee’s novel as a set text to show how language and societies evolve over time. Or contrast it with James Baldwin’s seminal work The Fire Next Time, published only three years after Mockingbird came out.

Baldwin’s book tells his personal story of growing up in Harlem and explores the wider narrative of racism that has characterised America since 1619 when the first enslaved Africans were brought to the British colony of Virginia. Reading the two classics together would surely increase students’ understanding of humanity. The good and the bad. And that is, surely, the point of great literature. To make us think.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShakespeare’s depiction of Shylock in the Merchant of Venice, written 400 years ago, is viewed by many, with good reason, to be anti-semitic, but should Shakespeare be cancelled? Of course not, but his anti-Jewish tropes should be challenged when students study the play.

Watching re-runs of the comedy classic Frasier during lockdown, I was struck by how inappropriate many of its funniest lines would be now, only 15 years after the last episode was aired. Yet I still laughed, because I understood the context.

Context is everything. Teachers should not be binning books, but using the best of them to help young people understand that, as societies progress, so language changes and ideas evolve. History is a moveable feast. The past is a difficult, challenging place.

As human rights campaigner and emeritus university professor, Sir Geoffrey Palmer, said earlier this week: “We can't just throw the book [To Kill a Mockingbird] in the bin. It’s part of the story of racism. We need to keep it, teach it and explain it.”

Later this month, the David Livingstone Birthplace Museum will re-open after a substantial refurbishment. But it is much more than the bricks and mortar of this Blantyre building that have been renewed. The museum’s curators have looked again at David Livingstone’s life, in an effort to tell a more rounded story about his 30 years exploring southern Africa.

His wife, Mary Moffat, features more prominently in the exhibition, as do the stories of the African people Livingstone lived with for most of his adult life.

Livingstone’s reputation has ebbed and flowed over generations, as our understanding of colonialism has evolved. When he was alive, he was hailed as a national hero, a great explorer and ferocious anti-slavery campaigner.

But in recent years, there has been a growing tendency to dismiss Livingstone as just another white colonial who exploited sub-Saharan Africa for his own ends. The truth is, as always, much more complex. He was unique. A self-educated, working-class man who travelled from his home outside Glasgow to explore an unknown continent with little more than a Bible, a compass and unshakeable belief in himself to guide him.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis conviction that Christianity, civilisation and commerce were key to Africa’s development sounds, to our contemporary ears, like nothing more than crude colonialism. Change them to development, education and trade and you have the pillars of sustainable global development as espoused by the UN today.

As I explore in my book, The Spirit of Malawi, Livingstone’s only contribution to the horrors of colonialism was to map out the territory that others later exploited. His legacy has always been better understood in the lands that he explored, such as Zambia where he died and Malawi, whose largest city is named Blantyre in his honour. There he is regarded, not as a colonial overlord, but as a man who fought to end the East African seaboard slave trade.

Speaking in 1973, on the 100th anniversary of his death, President Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia said, “What dominated Livingstone's life was his sense of mission as a servant of the people of Africa.” By including more African voices, the curators of Livingstone’s museum will help all of us understand much better the impact he had on the world. And it will help better explain colonialism.

As will a statue by a Malawi-born artist, Professor Samson Kambula. His work ‘Antelope’ has just been chosen to be displayed on Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth from next year. It represents Malawi freedom fighter and pan-Africanist John Chilembwe, a key figure in the resistance to colonialism in Malawi. He was executed in 1915 after a failed rebellion against British settlers who had taken over large swathes of land and exploited local labour.

The chief executive of the Scotland Malawi Partnership, David Hope-Jones, welcomed Professor Kambula’s achievement with some thoughtful words. “We understand the desire held by many to tear down statues which are no longer in keeping with our values today,” he said, adding, “But we think it is perhaps most important that we build new statues, literal or figurative, to ensure the role played by key black figures is not forgotten.”

It is only through a complex patchwork of stories that we fully understand our past, and so shape a better future. To Kill a Mockingbird is as important an element of the history of American civil rights as is The Hate U Give, the book James Gillespie’s has chosen to replace it.

David Livingstone is as significant a figure in the history of Malawi as John Chilembwe. Understanding both men – the good and the bad of them – helps us better understand our colonial past.

Cancel culture, whether it is books or people that are being erased, is a lazy response to understanding complex human stories. It is also dangerous. There is more than one way to burn a book, and history teaches us how that ends.

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.