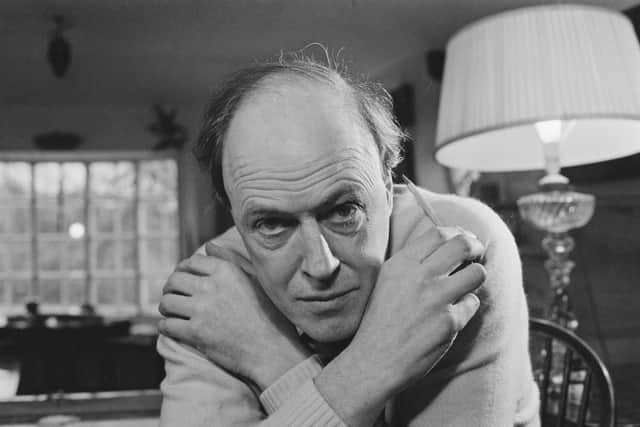

Cancel culture is getting out of hand. After Roald Dahl is 'edited' today, will we get 'alternative' versions of Robert Burns, Jane Austen and William Shakespeare tomorrow? – Christine Jardine

It only seems like yesterday that Nicola Sturgeon’s SNP were striding back into power for another five years with a unity of purpose and message that our UK Government could only envy. Nationalists must have felt that their dream was within touching distance.

Now it looks to the outside observer that simply holding things together could be the biggest challenge that their new leader will face. It would be disingenuous to suggest that the schism had been a complete shock to those of us who share a working base with the nationalists at Westminster. Tensions have been obvious for a while.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTwo of their MPs had already peeled off to join the renegade Alba party some time ago. But it is the speed with which the carefully woven picture of cooperation and harmony has been ripped apart that has taken us all by surprise, the bitterness of the public in-fighting which has shocked.

I know from my own political experience that leadership elections are not always easy or celebrations of unity. Offer two or more people a glittering political prize and they are liable to compete for it. We have always known that the SNP was the broadest of churches, people of various often-contradictory views held together by a commitment to the single goal of independence.

The same can be true to a lesser extent of other parties whose coalition of views can occasionally find it difficult to sit comfortably together. Five Conservative Prime Ministers since 2010 have struggled to cope with competing internal factions. Labour too had their share of internecine strife over the past eight years.

So we should not regard the current ructions in the SNP as an exclusively nationalist phenomenon. But neither do I believe that it is a purely political one. The past few months have been a difficult time for all of us, challenged as we have been to find our own place and hold true to ourselves in a toxic atmosphere that has pervaded debate in Scotland.

The bitterness and division over independence in wider society are well documented. Add to that a second equally divisive and even more personal issue of identity politics and you are playing with fire. We have all been burned to some extent.

For most of my career, I have found it easy to steer a middle course. Listen to the arguments. Take them all on board. Look for consensus. Protect the weak and stay true to my own beliefs.

By that, I don’t solely mean a political manifesto, but the principles instilled in me by my parents, by my life experience and the desire to protect those that I love. Recently it has proven more difficult.

In Scottish society, we have somehow found ourselves at a crossroads. And not the constitutional one which we might have anticipated. This is more about how we want modern Scotland, indeed modern Britain to look.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe late, much-missed Charles Kennedy used to say that he was a Highlander, a Scot, British and European. Each was a vital aspect of his identity. It is the same for many of us. We have already been deprived of our European-ness.

And it seems that politics for many Scots is a constant campaign to hold on to our Britishness, while being wrongly accused of doing that to the detriment of our Scottish identity. For much of the time that this argument has raged, we have ignored, or failed to nurture any part of, our common experience save conflict.

It would be far too simple, and cheesy to say that politicians should be nicer to each other. But it would also be true. This week I have listened aghast first to views being expressed and then to the reaction which followed. Surely, in a liberal democracy, tolerance is not just an abstract theory to which we give a nodding agreement but a core principle which we cherish, protect and nurture.

Too many of our discussions in this country have become polarised. Intolerant. We seem almost to have lost the ability to accept that just because people may see things differently their views should not automatically be dismissed. Decried. Cancelled.

And sadly, that appears to extend beyond politics into every aspect of life. Even children’s literature. Bringing Roald Dahl into a debate on political tolerance might seem like an exercise in incongruity. But for me, it betrays not only the same inability to tolerate different attitudes, but to fail to recognise the importance of learning from the past. Instead of regarding his writing as an offence to modern sensibilities, why not value it as an example of how we have developed?

Literature of the past – yes including children’s literature – is a valuable window on history, its attitudes and its influences. If we start to dismantle that where do we stop? Enid Blyton, Agatha Christie and others have already been ‘updated’. Who next? Burns, Austen, Shakespeare? Or perhaps like Dahl’s publishers, their’s will offer buyers the choice of original or ‘modernised’ versions according to taste.

And while we might think we are protecting our children, I heard a notable psychologist this week argue that by sanitising their literature, television and every cultural experience, we are undermining their resilience. Their ability to hear a different view and recognise it for what it is and present their own argument or view.

It’s arguably the trait we need most if we are to develop our inclusive, open-minded society which values people of all genders, sexualities, faiths, ethnicity and political views. To paraphrase Voltaire, to allow us to disagree fundamentally but defend our right to do so. Or is he about to be ‘edited’ too?

Christine Jardine is the Scottish Liberal Democrat MP for Edinburgh West

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.