Call for inquiry into Scots historical sex abuse

FRESH calls for a wide-ranging inquiry into historical child abuse in Scotland were made last night following claims by the daughter of a respected QC that she was sexually assaulted by her father and the Tory MP Nicholas Fairbairn in the 1970s.

Survivors of institutional sex abuse have been campaigning for a Scottish inquiry similar to those being set up by Westminster into allegations that influential figures, including politicians, colluded in and covered up the systematic abuse of vulnerable children.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUntil now they have been told previous inquiries in Scotland and the establishment of the National Confidential Forum – set up to give adult survivors abused in care a chance to talk about their experiences – make an over-arching review unnecessary north of the Border.

Last week, shortly after campaigners pressed their case at a meeting with Scottish government ministers, Susie Henderson waived her anonymity to allege she had been assaulted by her father, Robert Henderson QC, and Fairbairn, both of whom are now dead, from the age of four.

She said they were members of an organised paedophile ring which abused her in her family’s five-storey Georgian house in Edinburgh’s New Town and other locations.

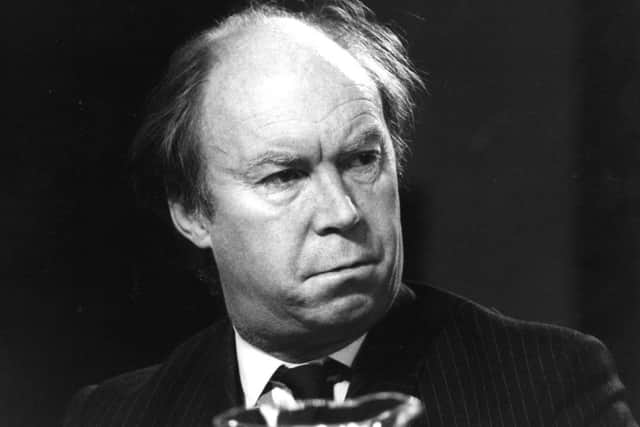

Fairbairn, a QC and former solicitor-general, has already been linked to the Elm Guest House in London – a gay brothel alleged to have hosted parties where vulnerable young boys had sex with influential people, which is now the subject of a police investigation named Operation Fernbridge.

Henderson was at the heart of the so-called Magic Circle scandal which emerged in 1989 and centred around rumours that a network of homosexual lawyers and judges in Scotland were conspiring to “go easy” on gay criminals. The rumours led to Fettesgate – where a 1992 police report into the claims was stolen from Edinburgh’s police headquarters – and ultimately led to an inquiry by William Nimmo Smith QC the following year, which dismissed claims of a conspiracy.

The Nimmo Smith report also took in concerns over Operation Planet, an investigation into a 16-year-old boy on leave from a children’s home who was drugged and raped by a group of men at an address in Edinburgh.

Susie Henderson made her claims in 2000 using the pseudonym Julie X, but backed off when details started leaking into the public domain. She said documents she passed to the police later went missing.

Yesterday, as the potential scale of the latest scandal became apparent, Labour’s justice spokesman Graeme Pearson – who first called for a public inquiry six months ago – said Susie Henderson’s claims demonstrated the pressing need for a Scottish investigation into all allegations of organised abuse and paedophile rings.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The problem from the survivors’ viewpoint is that the arrangements in Scotland, though costly, do absolutely nothing to answer the questions they have put over the years in terms of who was responsible, who allowed it to happen and what kind of counselling services could they access in order to deal with the many problems they still endure decades later,” Pearson said.

“There is a logic to the Scottish Government initiating a public inquiry now. It should cover all establishments which looked after children, but it should also be able to take evidence from anyone who claims that as a child they were abused in any kind of organised fashion.”

Pearson said there should also be an investigation into why the Fairbairn/Henderson case, reported to police in 2000, was dropped. “Given the new knowledge we have of the powerful people involved in some of these cases, I think the time is right to revisit this and get a clear understanding of what went on and to ask if [the case] was abandoned, was it abandoned for the right reasons?”

Susie Henderson claims Fairbairn – a friend of her father – first abused her when she was around four, sticking her hand up her skirt as Henderson looked on laughing. She says her father abused her regularly between the ages of four and eight, when her parents split up, and sporadically until she was 12, and that Fairbairn also raped her when she was four or five.

Her allegations have rocked the tight-knit Scottish legal establishment. Fairbairn, known for his flamboyant lifestyle, was a popular, if controversial MP, much favoured by Margaret Thatcher. Henderson was a leading defence lawyer oft-lauded for his powers of oratory. Last week, Lord McCluskey, also a former solicitor-general, said he was “utterly flabbergasted” by the revelations about Henderson.

Though shocking in their own right, their significance is heightened by the way they link to other scandals.

Not only is Fairbairn’s name said to have featured on a list of VIPs who visited the Elm Guest house in the 1980s, he was, for several years, honorary vice-chairman of the Scottish Minorities Group – a gay rights group set up by Scot Ian Dunn in 1969. Dunn went on to co-found the Paedophile Exchange Network which fought to legalise sexual relationships between adults and children, leading some to ask, how well did the two men know each other?

Meanwhile, Robert Henderson was at the very heart of the Magic Circle scandal. According to the Nimmo Smith report, he spread rumours of a network of gay lawyers and judges, encouraging journalists and others to believe he possessed a list of names that would “blow the legal world apart” when no such list existed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne theory was that Henderson sought to give the impression he possessed incriminating information as an insurance policy against charges relating to serious irregularities in his business practices which were levelled against him, then dropped.

Nimmo Smith said there was no evidence the case against Henderson had been dropped for anything other than bona fide reasons. But his daughter said her father once told her: “If I go down, I’ll take everyone else with me.”

The inquiry also touched on Operation Planet which involved a property in Palmerston Place, Edinburgh, owned by convicted sex offender and Bay City Rollers manager Tam Paton.

Earlier this year, Scottish government adviser Dr Sarah Nelson, who conducted a study into adult male survivors of child sex abuse, said she had uncovered a paedophile ring of influential figures centred on Paton and asked why this “Scottish Savile” had been ignored. She said a dossier on Paton had been prepared as long ago as 1982, but was never made public.

At the time when most of these events were unfolding, Conservative politics and the law were incestuously entwined in polite society in Edinburgh. By the Thatcherite 1980s, Scotland was effectively being run by a small handful of Tories, while most of its judges hailed from a small number of private schools, lived within a few hundred yards of each other in the New Town, and socialised together.

Fairbairn and Henderson not only moved in the same circles, but tried to enter parliament at the same time. In 1974, the year Fairbairn was elected MP for Kinross and Western Perthshire, Henderson was the unsuccessful Tory candidate for Inverness-shire.

If Fairbairn was guilty of child sex abuse, then it could be argued, that, like Savile, he was hiding in plain view. Eccentric and outspoken, he liked to boast about his voracious sexual appetite, albeit with women over the legal age limit. Twice married, he had a string of affairs – including one in the 1960s with Esther Rantzen – and listed his hobbies as “making love, ends meet and people laugh.”

He saw himself as a bon viveur, but others saw him as seedy. In an interview with Hunter Davies in 1992, he hinted a full-length mirror in his dressing room might be there so he could watch himself masturbating, called women who deny their femininity, “cagmags, scrub heaps, old tattles”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said: “Let us say I have spent all night screwing a mongoose, and next morning I have to appear in the House or in court. The vital thing is: does it show? If a sexually frustrated fellow, or woman, does not let their indulgence affect their professional performance, then b*******, it doesn’t matter.”

The journalist Ann Leslie claimed she had once had to sit through an edition of BBC’s Any Questions with his hand on her crotch.

Fairbairn hoped to be made lord advocate when Thatcher became prime minister, but his florid reputation counted against him and he was appointed solicitor-general. Though he survived one scandal – when his mistress Pamela Milne attempted to kill herself at his home – he was forced to resign over the infamous Carole X case in which he took the decision to drop the charges against three men accused of cutting and raping a Glasgow prostitute.

Fairbairn’s argument was that she was too traumatised to be a credible witness. He then breached protocol by explaining his thinking to a journalist.

Carole X later took a private prosecution against her attackers, all of whom were convicted.

In 1990, when speculation about the supposed network of homosexual judges had reached fever pitch, Fairbairn called for new legislation to allow newspapers spreading “false allegations” to be shut down.

The Magic Circle rumours first started circulating when Henderson was instructed to act for gay solicitor Colin Tucker, a junior partner in the firm Burnett Walker, who had been accused of embezzling thousands of pounds of clients’ money. Tucker’s defence was that he had been coerced into doing so by his sexual and business partner Ian Walker who had killed himself a year earlier. In the course of his defence, Henderson persuaded Tucker to write a potted history of his time with the firm which included lurid details of his and Walker’s many sexual exploits. The only other legal figure it mentioned was Lord Dervaird, a judge, who later resigned. In a clear breach of client confidentiality Henderson passed the statement on to other people, while giving the impression the information it contained was just the tip of the iceberg.

Soon the Edinburgh legal world was awash with speculation as to the identity of Magic Circle members – the names suggested included two judges, later cleared of involvement – who were letting gay criminals off the hook for fear of being blackmailed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy 1991, rising concern over the alleged conspiracy – and the failure to bring charges against Henderson who was by then being investigated over alleged irregularities in his business affairs – was running so high Detective Inspector Roger Orr was asked to launch his own investigation.

Orr’s report may never have been published had it not been stolen from the Police HQ by a small-time criminal and police informant and leaked to the press.

Its last paragraph gave some credence to the existence of a Magic Circle, prompting the Nimmo Smith inquiry and report.

Though Nimmo Smith found no evidence of any such conspiracy, he was scathing about Henderson’s behaviour, criticising the way he passed on Tucker’s statement and deliberately fuelled the gossip. As a result Henderson was fined £10,000 (later reduced to £5,000) by the faculty’s disciplinary tribunal.

Though the alleged offences pre-date the Magic Circle scandal by some years, Susie Henderson’s claims nevertheless reopen the wounds of a dark period in Scottish legal history. But – according to Pearson – they also reinforce the need for a Scottish child abuse inquiry that would look at what lessons could be learned from a range of cases, including the Fort Augustus Abbey saga.

The Scottish Government insists previous inquiries in 2007 and 2009 explored institutional abuse, addressed the particular challenges faced by the care system in Scotland and delivered major improvements. Since then, the Scottish Human Rights Commission has been working with others on an action plan on justice and remedies for those abused in care, which is due to be finalised in October.

But Pearson said the latest developments mean the Scottish Government needs to do more. “The fresh information we have gleaned over the last six months – and particularly last week – only adds weight to the idea that sensible people would conduct a public inquiry so we can be sure what has happened in the past has been properly dealt with,” he said.