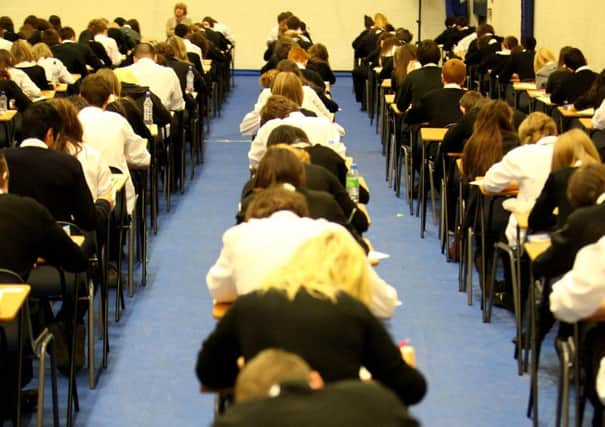

Brian Wilson: School tests - when will we learn?

IF YOU hang about long enough, everything comes round twice. Even by the standards of that maxim, it is startling to witness the return of National Testing as the centrepiece of Scottish educational reform.

Back in 1997, I became Scottish education minister at a time when National Testing had acquired a bad reputation. It was seen as divisive, in many ways counter-productive, burdensome on teachers and largely irrelevant to raising standards.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe put a brake on its planned extension into secondaries and the emphasis shifted to addressing problems which were obvious and urgent. Whatever money was available (at a time when the Scottish budget was £14 billion) it was diverted into pre-school provision, early Intervention and a huge increase in classroom assistants.

Thereafter, the Scottish Executive initiated a great debate on education policy. There were 25,000 responses and the vast majority supported an end to National Testing and publication of data which produced invidious, morale-damaging comparisons between schools operating in vastly differing environments.

Nobody questions the need for testing and, of course, testing has never stopped. Since then, every local authority in Scotland has made its own arrangements and schools are up to their ears in information it produces.

There is a case for standardising the tests throughout Scotland if the other baggage could be avoided. But it won’t be.

If this was an administrative tidying-up to use the same testing packages in all Scottish schools, it would scarcely have merited the place accorded to it in Nicola Sturgeon’s programme for government. The claim being made – just as in the 1990s – is that National Testing will of itself be transformational, producing “a range of key information to improve outcomes for every child in Scotland”. That is the fallacy. The document which accompanied Ms Sturgeon’s statement, while notably short on detail about implementation, stated ex cathedra that National Testing “will ensure that education in Scotland is continually improving … From 2017, teacher judgments will be informed by the new national assessments. This will ensure more consistency and reliability”.

Every word of that could have been written in the 90s and for all I know, the same people might be writing it. But there is minimal evidence to support these assertions. It also postpones anything much happening until 2017 and it will then need a few years to assess the emerging data. All this is far removed from the urgent needs of children who need help, right now.

We are told £100 million will be spent on reintroducing National Testing over a four-year period. By the standards of the Scottish Government’s exceptionally generous budget (currently £35bn) it may not be a huge amount. But every penny of it should go on addressing the well-documented needs of children in the classroom without the gimmicky rediscovery of National Testing as an elixir.

The purpose of testing should be to measure the progress and needs of each individual child and thereby support the work of the teacher and the school. What matters then is the application of resources to meet these needs and to ensure that the child does not fall behind at a critical stage in his or her development.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat is the very simple concept on which Scotland currently fails so many of its children. There is no single, easy method of addressing it since the needs of these children are often complex and deep-rooted. But the absolute certainty is that if these needs are not tackled and the playing-field levelled at an early stage in the child’s development, there is a diminishing prospect of that happening subsequently.

That is why the overwhelming priority for Scottish education – if there is any serious interest in redressing the chasm of unequal opportunity – should be to throw every available pound at early intervention and classroom support wherever it is required. It does not need a single extra test, far less £100m, to establish that principle tomorrow and then act on it.

The record has been very different. The focus on early intervention, which requires serious resources and has to extend beyond schools and into homes, was rapidly diluted even under the previous Holyrood administration. The number of classroom assistants and other vital support staff has been steadily eroding, as the Scottish Government has inflicted crippling cuts on local authorities.

In other words, the rhetoric is simply not matched by the reality. It is hypocritical to boast that reintroduction of National Testing will “improve outcomes for every child in Scotland” while the essential building blocks of delivery continue to be kicked away because the actual educational priorities of the Scottish Government have been so unrelentingly elitist.

The inadequate outcomes produced by the Scottish education system are well known and the really alarming fact is that they are getting worse, both in absolute and comparative terms.

A country which boasts of its egalitarian educational tradition, with great historical justification, now sends fewer of its children from low-income backgrounds to university than England and indeed just about anywhere else in Europe. Something has gone dramatically wrong and it needs addressing.

Unless that grave social injustice is addressed effectively, then all the other unequal outcomes in life will continue to flow from it. “National Testing to Address Huge Gap in Educational Achievement” is a headline for 2015 just as it was for 1995. Without a far-reaching review of Scotland’s educational priorities and how resources should be allocated, the 2015 version will be even less useful than its predecessor.

Meanwhile, I ask the question. If closing the educational opportunity gap had been the consistent first priority since Holyrood was created and investment in early intervention had continued at, say, twice the rate of increase in the overall Scottish budget in recognition of that priority, how different would the situation be today?

I know for certain that an awful lot of life prospects would have been transformed and Scotland would be a better, more equal country as a result. It’s never too late to learn.