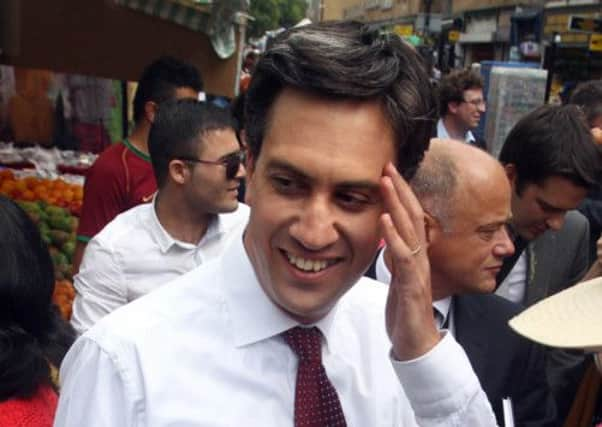

Brian Wilson: Miliband needs to look in the mirror

I have never been quite clear about why Ed Miliband wanted to be leader of the Labour Party or why he thought he should be. He has always seemed a decent, pleasant fellow. He was an able minister and competent communicator. His intelligence is certainly not in doubt. But while that adds up to an impressive CV, it scarcely answers the question.

Ed has now had two years to provide that answer and it is clearly still work in progress. His poll ratings are somewhere between dire and disappointing. The latest survey of Labour voters shows that fewer than half of them want him to lead the party into a general election in two years’ time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAdvice is pouring in from all quarters and some of it makes a lot of sense. Labour made a historic mistake in the wake of the 2010 defeat by allowing the Tories to rewrite the economic narrative, rather than robustly defending the generally creditable way in which the global crisis was responded to.

Once the lie was established that it had all been a mess of Labour’s making, it proved impossible to get off the back foot. So, Miliband and his unattractive shadow chancellor, Ed Balls, have spent far too much of the past two years apologising for the record rather than defending it, which is the prerequisite for offering a credible alternative.

A couple of months back, the London School of Economics published a major report entitled Policy, Spending and Outcomes 1997-2010, which tracked the effectiveness or otherwise of policies pursued through the lifetime of the Blair-Brown governments. It was a report card that any political party in the world could be proud of. So why doesn’t Labour use it?

In the words of the authors: “There is a myth that Labour spent a lot and achieved nothing.” But who has allowed that myth to take hold? Public spending went up by 60 per cent, but until the global crisis of 2008 was “unexceptional by historic UK and international standards”, while “national debt levels were lower than when Labour took office”. When did you hear Miliband or Balls pointing this out?

Most of the extra spending “went on improving services” – schools, doctors, nurses. The gap in infant mortality rates between richest and poorest narrowed by 10 per cent. Indeed, “the evidence shows that outcomes improved and gaps narrowed on virtually all the socio-economic indicators that were targeted”. Pensioners and children benefited most.

That accords pretty closely with my own recollections of a government I was proud to be part of. The LSE report reads mainly like a check-list of what the Labour Party exists to deliver. So, with a record like that to defend, how on earth have Miliband and Balls managed to end up with ratings on economic competence that lag far behind those of David Cameron and George Osborne?

Before it is credible to attack, it is essential to be able to defend. And that is one of the reasons why former Labour MP Chris Mullin was right last week that Miliband’s first step should be to involve people who were prominent during Labour’s time in government, who retain public trust and who actually believe that there is an honourable record worth defending. Alan Johnson and Alistair Darling are the most obvious examples.

Of course, there is a risk in that for Miliband because it is possible that he would not shine as leaders should in the company of their colleagues. But there is a bigger risk in ploughing on as before with a lightweight team that appears to hop from one opportunist issue to the next, has failed to develop a strong, appealing narrative and is hanging on to a poll lead that could be blown away by the first whiff of electoral grapeshot.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe more optimistic scenario is that, by strengthening his team, Miliband would himself be liberated to cut a more convincing figure as a potential prime minister. It would not take long to discover whether or not that outcome was likely to develop. And everyone, except Labour’s opponents, would be delighted if it did.

Anyone who seeks to be leader of a potential party of government has an obligation to look in the mirror and honestly answer the question: “Will the electorate ever assent to me being prime minister?” It is not a question that should be asked only once. The mirror should be returned to at occasional intervals.

It would have saved the Tories a lot of trouble if some of their recent leaders had subjected themselves to the mirror test: William Hague, Iain Duncan Smith and Michael Howard were simply never going to win. Being electable does not necessarily mean being elected – as Cameron almost found out – but it is still the essential prerequisite. Incidentally, it is interesting that two of these failed Tory leaders now occupy positions of prominence within the government. Giving leadership a decent shot and then getting out does not necessarily mean the end of a political career – a consideration that should make it easier for future doomed leaders to consider their options.

Labour has a dismal record of indecisiveness even when all common sense suggests that its leader is not going to make it past the winning post. Partly, this is due to the unwieldiness of its internal machinery while kindness and loyalty are also significant factors, though the true kindness would sometimes be to act rather than acquiesce.

I remember the Darlington by-election in 1983 when Michael Foot’s continued leadership hung on the outcome. Labour scraped home and he stayed. A few months later, Darlington went Tory – along with the rest of the country. Everyone knew what was coming, but nobody dared act. Again, in 2007, it was a lemming-like mind-set which determined that nobody stood against Gordon Brown, not least in the interests of his own mandate.

Ed Miliband is not yet at that stage. He needs to weigh the advice he is receiving, strengthen his team, focus his messages, bring in people who will defend Labour’s record and advance a credible alternative to the Tories, generally remind the electorate why they need a Labour government.

Then, having done all that, he should return to the mirror with, one hopes, enhanced confidence about the answer he will receive. But as an intelligent man with a great hinterland of Labour tradition, he should not flinch from asking himself the question.