Brexit: Theresa May should beware fate of Arthur Balfour – Bill Jamieson

So, Prime Minister, here is the question du jour: Where Are the Aces to be Found? Now that our fate seems to rest on a last throw of the dice, it seems pertinent to ask. Some years ago, in the midst of a recession and dismal prognostications from commentators, I was tasked to speak at a business conference on this very question. After all, it was easy enough to stuff the audience with reasons to be pessimistic. Where was the upside? What the audience wanted was hope. But aces? Four of them? I struggled.

This morning, after what have been hailed as parliamentary victories for the Prime Minister, we look over her shoulder to see what hand she is now holding. Aces to the fore? No, all we can see is a fistful of Jokers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhy the congratulations on the outcome of Tuesday night? She has somersaulted on her previous resistance to re-opening talks with Brussels and might be said to have turned a corner of sorts – only to face a solid brick wall. There is absolutely no sign that either the European Commission or the Irish government will agree to any re-opening of negotiations. On the legal text.

But after whatever talks take place, Mrs May would then bring her “revised” (sic) deal back to Westminster for yet another “meaningful vote”. If this has not happened by 13 February, the Government would be likely to table an amendable motion for debate the following day – by the grimmest of ironies, St Valentine’s Day. Yet more stand-offs, tortuous amendments, shouty interviews on radio and television – and all for what? Another crushing defeat? How long can the public’s patience endure – if it has not already been stretched enough?

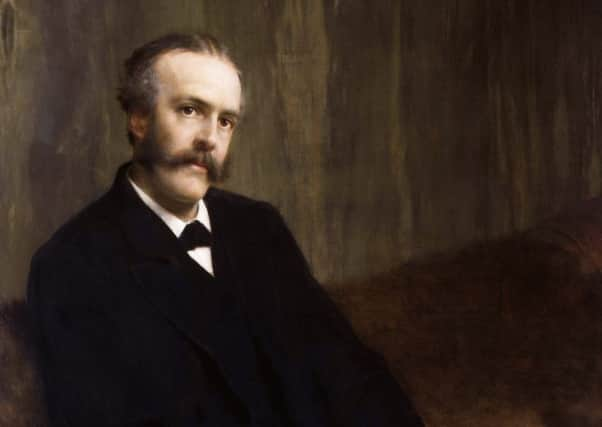

Little wonder that it is tempting to look for historical parallels for a crisis of this magnitude. One that hardly fits in all particulars but which I believe comes uncomfortably close is the fate that befell the Scottish Prime Minister Arthur Balfour and his stand-off against Joseph Chamberlain over tariff reform in 1903-06.

“What did Balfour really believe?” was the question repeatedly asked of him – inside the Cabinet and without. In his sphinx-like mode, he seemed absolutely resolute, with one critic summarising his views thus:

“I’m not for Free Trade, and I’m not for Protection;

I approve of them both, and to both have objections.

In going through life, I continually find

It’s a terrible business to make up one’s mind.

... So, in spite of all comments, reproach and predictions,

I firmly adhere to Unsettled Convictions.”

His desperate quest for a middle between the two wings of his party – one solidly for continuing free trade, the other for imperial preference – exasperated parliament and drove him ever deeper into a quagmire of confusion and uncertainty. His quest for a middle way – tariff reform light, with retaliatory tariffs, but neither a general protection of industry nor food taxes – sounded equivocal when tested. And “unsettled convictions” were no match for the magnetic, charismatic appeal of Chamberlain in full flow.

Balfour was not above resorting to hints at a general election to resolve the battle. It was not, he declared, “a question that this House will have to decide this session or next session or the session after. It is not a question that this House will have to decide at all.”

The battle divided the government and Churchill was among ten other ‘free trade’ Unionist MPs who crossed the floor of the house. How did it end? It split the Unionist party, shortened the lifespan of the government and destroyed it utterly at its end when it lost the 1906 election to fellow-Scot Campbell Bannerman in a sensational wipe-out. Balfour lost his seat and the Unionists held on to just 157 seats to the Liberals’ 400. In due course, other issues came to the fore – Irish home rule, the People’s Budget, the battle over the House of Lords, the rise of Labour, and the deepening shadow of war in Europe. Balfour lost two further elections before finally resigning in exhaustion as Unionist party leader in 1911, to be succeeded by Bonar Law – and a world utterly changed.

There are differences, certainly, between then and now – but ominous echoes, too. For after a modern-day splitting of the governing party there would more – much more – that would lie beyond.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWere the final outcome “simply” to be a car crash in two weeks for the Prime Minister’s Withdrawal Agreement, followed by departure from the EU with no deal, this would be crisis enough to make this period one of the most fateful in modern political history.

But still to come is a deadly reckoning with voters in a general election. Even if the worst of ‘no deal’ can be avoided – the fresh food shortages, the empty shelves in supermarkets, the chaos at ports, the NHS rationing of medicines, and security patrols on the Irish border – voters will be in a sulphurous mood after the parliamentary shenanigans of the past two-and-a-half years.

The Conservatives may take comfort in the belief that voter memories will quickly fade and matters return to some semblance of previous status quo. But memories did not fade in the four-year aftermath of the ERM debacle when the Conservatives were trounced in the Tony Blair landslide of 1997. And today the opposition leadership of Jeremy Corbyn and the avowedly Marxist John McDonnell is of an altogether different belief and character to previous Labour administrations.

Be in no doubt as to what lies in store. This will be more than a contest between two candidates for the UK premiership. It will be more than a contest between two parties. It will be a contest between two sharply different philosophies of government, with fundamental divisions overlaid by an insurgency of populism and identity politics. Here in Scotland the SNP may pose as the liberal, progressive party of “everywhere”. But its grassroots support draws deeply from that well of identity politics and a populist insurgency for sovereignty and independence as uncompromising as anything that has faced precious Westminster administrations.

Where are the aces to be found? Bleak though it all looks, and with little to give comfort, we have a fundamental duty to keep looking.