Boris Johnson beware. Scots MPs brought down Jim Callaghan and even tried to oust Winston Churchill during Second World War – Alastair Stewart

The tokenistic title has meant nothing to the battle for the Union or to Scots. The Prime Minister is now such a liability that the leader of the Scottish Conservatives has called for his resignation.

Johnson is not the first Prime Minister to hold dual roles. His great hero Winston Churchill was minister for defence and premier during the Second World War.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThen, as now, Scots hold more power than they think in determining the occupancy of Downing Street. And it is mythmaking to suggest otherwise.

Consider the facts: Winston Churchill was the right man at the right time in 1940. By 1945, the British people gave him the order of the boot and resoundingly voted him out.

Twice in those war years, Churchill was forcibly challenged to account for his conduct of the war effort. Twice, it was two Scots who played a central role.

In his war memoirs, Churchill called 1942 “a long succession of misfortunes and defeats”, notably with the capture of Singapore by the Japanese and defeat at Tobruk.

Backbench frustration at the war's conduct had necessitated a vote of confidence in January that year. Churchill was determined to call their bluff – or, as one of his successors was to say 50 years later – force his opponents to “put up or shut up”.

Churchill's Labour deputy Clement Attlee tabled the government motion: “That this House has confidence in His Majesty's government and will aid it to the utmost in the vigorous prosecution of the war.”

The Prime Minister opened with a two-hour speech setting out his record and closed with a 40-minute one. MP Harold Nicholson recorded in his diaries that “by the time he finishes, it is clear that there is really no opposition at all – only a certain uneasiness”.

Churchill was keen to see a division called to record his support, and 465 members obliged the Prime Minister.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut a victory is meaningless without the contrasting odds against it. And on 29 January 1942, James Maxton, Labour MP for Glasgow Bridgeton and chairman of the Independent Labour, obliged history and was the only one to vote against Churchill.

Maxton is remembered as one of the leading figures of the Red Clydeside era and a leading pacifist and conscientious objector. His biographer Graham Walker concludes: “Maxton was one of the most charismatic figures in 20th-century British public life.”

Churchill bore few grudges. After Maxton died in 1946, Churchill said his “views were very different from mine” but paid tribute to him as “the greatest gentleman in the House of Commons”.

Churchill survived that vote, but a motion of censure against the UK government's conduct of the war was tabled later in July. This time it was by another Scot, the Conservative MP Sir John Wardlaw-Milne.

During June and July 1942, he attempted to force Churchill out in a vote of no confidence. A two-day debate of confidence was scheduled, with the motion: “That this House, while paying tribute to the heroism and endurance of the Armed Forces of the Crown in circumstances of exceptional difficulty, has no confidence in the central direction of the war.”

The motion gained initial support mainly in response to British losses in North Africa.

Sir John's opening salvo demanded the partition of Churchill's joint role as Prime Minister and minister of defence. “As a result of combining the two sets of duties to which I have referred, I suggest to the House that we have suffered in both fields.”

His solution was ambiguous – he wanted either a generalissimo figure to run the war alone or a diarchy between a new head of the armed forces with a dominating prime minister.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe seconder of the motion, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes MP, confused matters further when he accused the Prime Minister of not taking enough interest in the direction of the war.

Reverend Campbell Stephen MP, a fellow Scot and a close friend of Maxton, neatly surmised the fiasco when he said: “I am rather confused at the course the debate is taking. I understood… a vote of censure on the ground that the Prime Minister had interfered unduly in the direction of the war. The seconder seems to be seconding because the Prime Minister has not sufficiently interfered in the direction of the war."

The debate never made any real in-roads. Churchill, again, survived. Nicholson records that Sir John “is in fact rather an ass”. The vote was defeated 476 to 25.

As Churchill declared, votes of confidence and censure are a “considerable event”. He repulsed his second challenge and was defiant: “...the duty of the House of Commons is to sustain the government or to change the government. If it cannot change it, it should sustain it. There is no working middle course in wartime.”

These events by two Scots MPs, whose political differences were extreme, are largely forgotten. But they join others, neglected too.

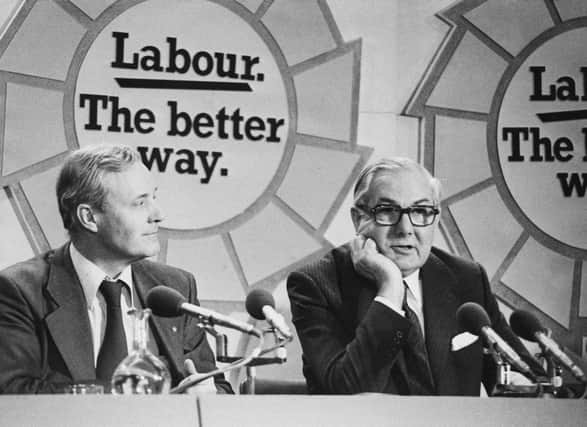

The SNP tabled a no-confidence motion in Labour Prime Minister Jim Callaghan in 1979. The Conservative Party laid their own motion of no confidence, which the SNP's 11 MPs voted for, bringing the government down.

Callaghan rightly remarked, “that it is the first time in recorded history that turkeys have been known to vote for an early Christmas”.

Labour was defeated at the subsequent general election that year. The SNP launched their bogeyman in Margaret Thatcher for the next 11 years and “the Tories” for another seven.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnyone who suggests Scots have not been vital to the direction and future of the United Kingdom does not know their history.

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.