Black Lives Matter: Meet Francis Williams, the 18th-century lawyer and poet dismissed by Scottish philosopher David Hume as a 'parrot' – Dr Robin Mills

Williams, who lived from circa 1690 to 1762, was the first black writer to gain prominence within the British Empire. His story is fascinating in its own right and shows the tendency to co-opt people’s stories for political point-scoring was as apparent in Williams’ own time as it is in our own.

In the late 18th-century, Williams was cast as a debating point in the dispute over slavery. Much of this controversy revolved around whether Williams’ poetry was really any good. This may seem ludicrous, even laughable now, but writing poetry was taken as evidence that Williams could participate in the activities of an educated gentleman of his time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf he demonstrated skill and creativity in composing Latin verse, and expressed his humanity along the way, then pro-slavery arguments, centring on the supposed inferiority of the enslaved people, were undermined.

In Britain, the story had circulated that Williams had been educated at the University of Cambridge, at the Duke of Montague’s expense, to test this very proposition: whether enslaved Africans could reach the same educational levels of white Europeans.

To abolitionists, Williams’ subsequent achievements demonstrated the equality of humans and the illegitimacy of slavery. For the pro-slavery interest, Williams had to be cut down to size, exposed as unexceptionable for fear that his achievements would undermine the doctrines underpinning colonial slavery.

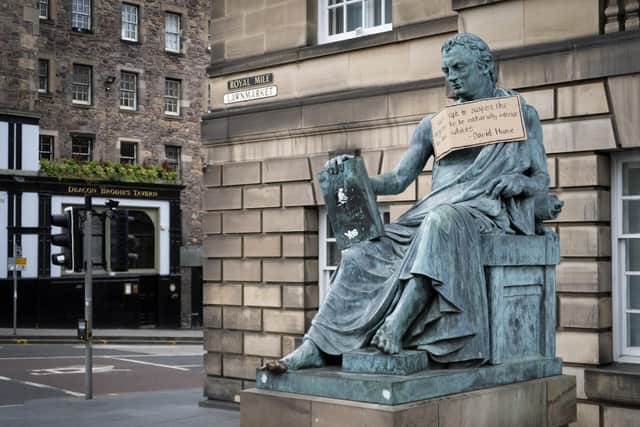

To Hume, Williams was probably “admired for very slender accomplishments” and his literary productions were the equivalent of a “parrot” trained to repeat a few words. In his History of Jamaica (1774), Edward Long, the cartoonishly repellent defender of slavery, tried to destroy Williams’ reputation. Ironically enough, in doing so, Long brought Williams’ poetry to the world’s attention. Williams’ ‘Ode to George Haldane’, a Latin ode to the newly appointed Governor of Jamaica penned in 1759, only reached wide public attention because of Long’s translation and criticism.

Overturned restrictions on freed slaves

In his Ode, Williams asserts our common humanity, boasts of his own talents as much as Haldane’s, and celebrates British rule. Williams writes that “a bountiful God has given the same soul to all kinds of men” and that “virtue itself has no colour, nor does understanding”. Williams attributes to himself “upright morals”, “desire for learning”, “a wise heart and a love of ancestral virtue”. Williams is proud of his Jamaican birth, his British education, and his place within the colonial hierarchy.

The notion that Williams was an English duke’s project was a good story. It is also probably not true. Williams and Montague were born around the same time. The Duke was unlikely to be thinking up sociological experiments while himself a schoolboy. Williams was educated in Britain, but as a lawyer at Lincoln’s Inn in the 1720s, and not Cambridge. He was financed not by a noble patron, but by his own father’s fortune.

Williams’ father, John Williams, was a freed slave. He became a successful merchant in Jamaica, powerful enough to force the Jamaican Assembly to extend to him the legal privileges usually reserved to whites. Williams senior then forced the Assembly to extend these privileges to his sons. Williams inherited his father’s fortune in 1723 and became one of the richest men in Jamaica. This fortune included a plantation, slaves, and moneys owed by many prominent white Jamaicans.

Williams did not inherit his father’s business acumen or enthusiasm. He had frittered away his inheritance by the time of his death in 1762. But his legal training gave him the skills and experience to push back against local efforts to take away his privileges as a freed slave. The Jamaica Assembly’s 1730 act restricting the freedoms of freed slaves was overturned by the Privy Council in London in 1732 following Williams’ petitioning.

Proposed as a Royal Society member

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWilliams was a free-born black lawyer, able to use the Empire’s legal system to oppose racism. He was a proud, educated, rich (though decreasingly so) and powerful man, willing and able to fight to enforce the legal rights extended to him. In this, he had powerful white friends in Jamaica. Likewise, powerful friends in London proposed him as a member of the Royal Society in the early 1720s – though an overwhelming number of members rejected his candidacy on the grounds of his race.

But there is a painful irony at the heart of Williams’ story. He fought against white supremacy in Jamaica and his literary talents were used as evidence by abolitionists of slavery’s baseless intellectual foundations. Yet he aimed to enjoy his rights as a slave-owning gentleman and in his poetry was content to praise continued British rule, while celebrating his own standing within the colonial hierarchy.

As historian of abolitionism Vincent Carretta notes, bringing stories like Williams’ back to the fore, demonstrates "the complex relationship between race and status in the British Empire during the 18th century”.

What do we make of Williams now? He was nominated for inclusion in Patrick Vernon’s 2004 list of 100 Great Black Britons, on the basis of his poetry and before the full story of Williams’ life was known. He did not make the cut then, nor in the just-published 2020 list organised by Vernon and Angelina Osborne.

“The tragedy of Francis Williams,” says John Gilmore, a Warwick historian who, like Carretta, has done much to recover the truth of Williams’ life, “was that he never seemed able to understand why a rich, educated black slave-owner should not be treated in Britain or Jamaica in the same way as a rich, educated white slave-owner”. It is appreciating figures in their historical complexity that is the most interesting and humane endeavour.

Dr Robin Mills is a Leverhulme early career fellow in history at Queen Mary University of London

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

The dramatic events of 2020 are having a major impact on many of our advertisers – and consequently the revenue we receive. We are now more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription to support our journalism.

Subscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app. Visit www.scotsman.com/subscriptions now to sign up.

Subscribe to the Edinburgh Evening News online and enjoy unlimited access to trusted, fact-checked news and sport from Edinburgh and the Lothians. Visit www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com/subscriptions now to sign up.

By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Joy Yates

Editorial Director

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.