Bill Jamieson: Fact and fiction in fight for votes

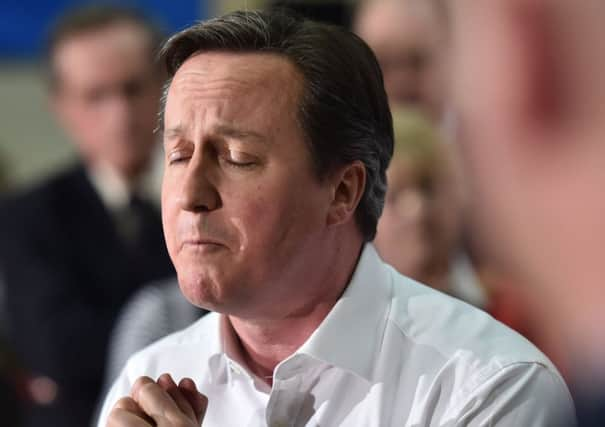

At Team Cameron HQ, deep frustration must be setting in. “Good news” is showered upon us. But it has brought no surge in support for David Cameron with the election just five weeks away.

In the past week we have had upward revisions to GDP growth, a Purchasing Managers Index survey for manufacturing at an eight-month high, mortgage approvals up, figures showing real living standards now above their 2010 level and authoritative surveys declaring that consumer confidence is now at its highest since 2006.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYet the poll dials have barely twitched. None of this is earning Cameron any points in voter support. Ed Miliband is breathing down his neck and on recent polls Labour was shown to be four points ahead. Nor in Scotland does it look as if the good news will stop the SNP surge: the party is on course for an epochal victory and to be a muscular power broker at Westminster.

Welcome to the great paradox of this election.

It may be that voters are reticent about disclosing their voting intentions. Or that voters, far from being galvanised by the campaign, are already heartily sick and tired of the soundbite slogans on “long-term economic plan” and “Miliband Labour chaos”.

The most popular explanation is that millions of voters do not sense this economic upturn and indeed are more likely to be feeling a measure of apprehension and resentment – that the “good news” is for other folk and that they are missing out. Thus, instead of every fresh “good news” statistic boosting their sense of well-being, it adds instead to their sense of injustice.

And you don’t have to look far in Scotland for injustice.

The big story at local level remains one of cuts in local services, budgets being curtailed and high streets looking dilapidated. To this, Scottish Labour seems unable to offer a credible change to a state of affairs over which it has long presided.

But what of the SNP’s own “sunny uplands”? Every week has brought fresh SNP declarations on “fighting austerity” and “resisting Tory cuts”. Pledges to combat income and wealth inequality are interwoven with lists of spending pledges, down to the reaffirmation of the party’s commitment to free school meals for every P1-3 child in Scotland, “saving at least £330 per year for each eligible child”.

Who but a heartless ogre would curtail such benefits or reduce welfare benefits, or not hire more nurses or end food poverty or maintain the range of “free” universal benefits?

And who would jibe at more money for capital spending projects, or road and rail improvements, or better schools and above all, more housing?

But who are the real heartless ogres here? How about those promising to deliver all these things in an election while every reliable statistic points to huge constraints, both on local council and Scottish Government spending as far ahead as we can see?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe SNP campaigns for full fiscal autonomy and “more powers” for the Scottish Parliament as if the mere recitation of these demands will itself deliver the wherewithal to finance those spending pledges.

What is the reality in Scotland? Where exactly are these “sunny uplands”? Look at the financial state of local councils. A report by Scotland’s spending watchdog reveals the extent of local authority debt run up to get round the council tax freeze. The figures revealed that councils have a total debt of £14.8 billion, with 82 per cent of this total (£12.1bn) as a result of borrowing. The report, from Audit Scotland, reveals that 17 councils out of 32 have increased their borrowing levels over the last ten years.

Now look at the picture at national level. Here the independent Institute for Fiscal Studies released a succinct but sobering summation of where we are headed. It has calculated the effect of the plunge in oil prices together with other forecasting changes. It says these point to reductions in forecast revenue even more dramatic than those anticipated by the Office for Budget Responsibility.

Under its earlier projections based on the OBR’s December 2014 forecasts, Scotland would have been looking at a deficit of around 8 per cent of GDP in 2015-16.

However, the OBR’s latest forecasts imply Scotland’s North Sea revenues will fall to around £0.6bn in 2015–16. This, says the IFS, would mean Scotland’s budget deficit would be 8.6 per cent of GDP in 2015-16 – more than double the projected budget deficit for the UK overall. In cash terms this is equivalent to a gap of £7.6bn.

“Sunny uplands”? Not on these numbers.

Now consider what lies ahead. English regions are on the move. There is Osborne’s championing of the northern English cities powerhouse plan. There are the recently announced £650 million inward investment wins for the Midlands – £400m for a new Tata Motors Jaguar Land Rover engine plant and £250m by China’s Zhejiang Geely Group for a new taxi manufacturing plant expected to create 1,000 jobs.

Note also the HSBC announcement to relocate its HQ in Birmingham. Elsewhere, local authorities in the south-west of England are angling for economic devolution powers.

In a world of ever more capital, all this suggests intensifying competition ahead for investment and jobs across the regions and nations of the UK. And as that competitive threat gathers pace, Scotland’s current disaffection could quickly turn to a state of existential panic. This may well be why “good news” is not working for Cameron-Osborne but, on the contrary, adding to that voter scepticism and the sense of “missing out”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSeldom have we gone into an election with such scepticism over Westminster “sunny uplands” portrayals – yet at the same time with a near total suspension of disbelief on what “more powers” might bring.

We are asked to set aside all the constraints on what a UK government might deliver while accepting with barely a murmur what “more powers” by themselves would deliver. It is a fantastic, delusional prospectus that has us revving up into a brick wall of reality.

Only successful competition for investment and jobs will deliver those “sunny uplands”. The competition is for real. The rest is fiction.

FOLLOW US

SCOTSMAN TABLET AND MOBILE APPS