Bergdahl: Homeland drama strays from Obama script

THE whirr of helicopter blades over scrubland in the Khost province of Afghanistan last week signalled the beginning of the end of US army sergeant Bowe Bergdahl’s five-year ordeal at the hands of his al-Qaeda-linked captors. Moments before the Black Hawk landed, the 28-year-old soldier could be seen sitting in a pick-up truck – clean-shaven but gaunt, apparently confused and blinking like a pit pony – as insurgents armed with rifles and a rocket-propelled grenade launcher hovered ominously in the hills.

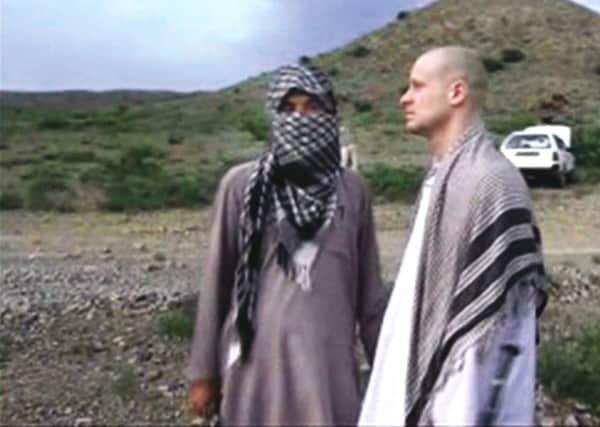

Captured on a Taleban propaganda video, the fleeting handover, consisting of a couple of awkward handshakes and a frisking of Bergdahl by his rescuers, should have been the precursor of a joyous homecoming and a moment of triumph for President Barack Obama’s administration; by bringing back the country’s last prisoner of war, the president would help secure his legacy as the leader who not only presided over the successful mission to find Osama bin Laden, but successfully extricated the United States from its 13-year “war on terror”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCertainly, the stage was set for national celebration. Hours after Bergdahl boarded the helicopter, Obama joined the soldier’s tearful parents Jani and Bob in the White House Rose Garden to announce the good news. Thousands of miles away in Bergdahl’s home town of Hailey, Idaho, the atmosphere was similarly euphoric. Porches and lampposts were festooned with balloons and yellow ribbons, and civic leaders were busy organising a homecoming party.

Caught up in their successful delivery on one of the US military’s articles of faith – No Man or Woman Left Behind – Obama’s advisers must have figured America’s delight in Bergdahl’s return would not only offset disapproval over the five senior Taleban commanders released from Guantanamo Bay to secure his freedom, but divert attention from the damaging Veteran Affairs scandal: allegations of long waiting lists and fatally poor care at VA hospitals and clinics.

Instead, the story that has unfolded has been closer to the plot of Obama’s favourite TV show Homeland, about a US marine “turned” by his Islamist abductors, than the populist coup he had hoped for. Where Homeland’s fictional protagonist Nicholas Brody was feted before falling under suspicion from the CIA, Bergdahl has been branded a “deserter” before he has set foot back on US soil (he is currently being held in a German military hospital until his health improves).

Though his father’s appearance and behaviour at the press conference – he turned up with a Taleban-style beard and quoted a line from the Koran in Arabic – was unexpected, it was nothing to the revelations that followed. A succession of former servicemen have claimed Bergdahl was captured after deserting; that the search for him led to the deaths of other soldiers; and that he ought to be court-martialed. If all this wasn’t damaging enough, it has emerged the scandal was covered up at the time.

As the controversy over Bergdahl’s capture escalates, Republicans (and quite a few Democrats) have been lambasting Obama over the terms of the trade. They say he has breached another fundamental US tenet by negotiating with terrorists and has broken the law by failing to give Congress 30 days’ notice of the transfer of prisoners from Guantanamo.

The White House’s argument – that the swap was brokered quickly after a new video showed Bergdahl’s health was failing – might have garnered more sympathy if leaked e-mails from the PoW had not outlined his growing disaffection with the war and the US (“These people need help, yet what they get is the most conceited country in the world telling them that they are nothing and that they are stupid, that they have no idea how to live,” he wrote) and had his father not tweeted “I am still working to free all Guantanamo prisoners. God will repay for the death of every Afghan child” to a website which claims to be the Voice of Jihad.

So suddenly and savagely has the public mood turned against Bergdahl, the homecoming in Hailey has been cancelled and those who initially seemed to support Obama’s decision are distancing themselves. Hillary Clinton has let it be known that she opposed a prisoner swap the last time it was broached in 2012. And Dutch Ruppersberg, the senior Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee, said the swap set “a dangerous precedent that puts all Americans at risk across the world”. Only senate majority leader Harry Reid and house minority leader Nancy Pelosi have stood squarely behind the president. Meanwhile, the Right are having a field day, linking the Bergdahl deal to the so-called Benghazi scandal, which revolves around claims the president knew the attacks on the US diplomatic mission and a CIA annexe in Libya – in which ambassador Chris Stevens and three embassy staff died – were an organised terrorist plot and not an impromptu response to a YouTube video as was initially claimed and has been used to portray the president as an appeaser.

But the attempt to turn Bergdahl into another stick with which to beat the Obama administration threatens to distort a complex story which affords a rare insight into realities of life on the frontline and the contradictions and chaos of combat. Those intent on pigeon-holing Bergdahl – hero or villain, patriot or traitor – are ignoring evidence of his mounting inner conflict and the morally ambiguous circumstances in which he found himself.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA much more nuanced perspective of the events leading up to Bergdahl’s disappearance in June 2009 is provided by award-winning journalist Michael Hastings in an article for Rolling Stone in 2012. Having spoken to his family, friends and fellow soldiers, Hastings draws a portrait of an interesting if idealistic young man: a home-schooled philosopher and Bear Grylls wannabe, who learned to shoot in the hills of Idaho and dreamed of making a difference. Rejected by the Foreign Legion, he bought into America’s purported hearts-and-minds strategy in Afghanistan and signed up to the 25th Infantry Division. Capable, committed and unusually intense he was bewildered to find himself in a platoon beset by discipline and morale problems. While other soldiers spent their free time letting off steam, he would read, work out and learn Pashto. He wasn’t the only soldier to be disillusioned with the way in which the war was being waged, but his disillusionment seems to have run particularly deep. “We don’t even care when we hear each other talk about running their children down in the dirt streets with our armoured trucks,” he wrote in his last e-mail to his father. “We make fun of them in front of their faces then laugh at them for not understanding we are insulting them.”

The circumstances surrounding his disappearance are indeed murky. Though he had posted his laptop and clothes home half-way through his 12-month deployment, it is unclear whether he wandered off, deserted or even defected from his base in Patika. Some army sources point out he had gone missing before (and then returned), but others insist an increase in the frequency and accuracy of IED (improvised explosive device) attacks in the weeks that followed suggest he was actively collaborating with the enemy. What seems certain is that he was held by Haqanni militants for five years in various locations in Pakistan. Fox News claims to have seen documents suggesting that at some point during his captivity he converted to Islam, carried a gun and fraternised with his kidnappers, but other sources insist he twice tried to escape his kidnappers.

Also murky is the suggestion that six US soldiers died as a direct or indirect result of Bergdahl’s actions: several former servicemen insist the men lost their lives while out searching for him, but the Pentagon has not confirmed this. As for his father, opinions in the US are divided: to some his decision to grow a beard, learn Pashto and communicate with Taleban commanders make him suspect, but old friends in his hometown believe he’s just doing the best he can for his son.

The controversy also provides an insight into the ethical dilemmas facing Obama as he tries to end the conflict in Afghanistan. Last month he pledged to bring all but 9,800 troops home by 2016, and the fate of the only US PoW was a loose end which had to be tied up, particularly given the shadow cast by the number of Vietnam MIAs (soldiers missing in action) whose true fate was never established. Unfortunately for the Democrat president, the Republicans claim that in doing so, he has breached another sacred US principle: no negotiation with terrorists.

In fact, several previous administrations have negotiated with terrorists (Jimmy Carter released billions of dollars of frozen Iranian assets to free 52 hostages from the US embassy while Ronald Reagan provided weapons to free hostages held by Iranian proxies in Lebanon) and, in any case, the White House maintains, with some justification, that the Bergdahl deal is more akin to a PoW swap than a bowing down to hostage-takers. Even so, given that, in 2012, the director of National Intelligence James Clapper claimed 28 per cent of all detainees moved out of Guantanamo returned to terrorism, it’s a risky strategy which could lead to more deaths further down the line.

Despite the fall-out, Obama has defended his position. He believes the US has a duty to bring home its soldiers regardless of circumstances. As for the morality of doing a deal with the Taleban? “This is how wars end,” he said. Yet serious questions continue to be asked about the way he and his advisers have handled the affair. Even those who accept a deal was necessary struggle to understand why, given Bergdahl’s history, Obama chose to celebrate it publicly or to allow national security adviser Susan Rice to proclaim the PoW had served his country “with honour and distinction”?

Did no-one foresee that inviting the Bergdahls to the White House might feel like a slap in the face to bereaved parents whose suffering has not been formally acknowledged?

On top of all this is the failure to inform Congress about the prisoner release. Assurances that it all happened too quickly are unlikely to wash with anyone. A classified briefing at which the latest video of Bergdahl was shown has not convinced senators the deterioration in his condition was profound enough to justify such drastic action.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhatever happens to Bergdahl now, he has already forfeited any hope of a hero’s welcome. His “reintegration” is said to be progressing, though he has not yet spoken to his parents, but his mental state is unlikely to be improved by the news that thousands of people have signed a petition calling for him to be punished.

Despite his ordeal, it is still possible he will be court- martialed. US soldier Charles Jenkins who endured harsh treatment in North Korea for almost 40 years after deserting in 1965, was sentenced to 30 days for desertion when he escaped in 2005.

As for Obama, his enemies are now suggesting he ignored earlier chances to rescue Bergdahl.

And they said the plot of Homeland was far-fetched. Of course, it’s fatuous to draw too many parallels between a TV drama and real-life events, but it was the president who made such play of his admiration for the long-running series. As his own attempt to turn a potential PoW homecoming to his political advantage backfires, he must be wishing he’d taken its twists and turns a little more seriously.