Ashley Davies: Lyrics make the most out of music

When a good friend of mine was seven years old, she sang a song from the musical Annie to entertain neighbouring children and their parents at a party. High on attention, she refused to give up the stage and belted out – really belted out – a second, less age-appropriate number. In case you’re too young or fortunate to have heard Charlene’s I’ve Never Been to Me, it’s a self-indulgent confessional ballad about a woman whose hedonistic lifestyle has prevented her from finding real love, and boasts the line: “I’ve spent my life exploring the subtle whoring that costs too much to be free/I’ve been to paradise but I’ve never been to me.”

It wasn’t until years later that my friend’s mother told her how horrified the grown-ups present had been (I like to think there was also a priest present). A few decades on and she still has a remarkable facility for remembering lyrics, but at least now she understands what she’s singing (mostly).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

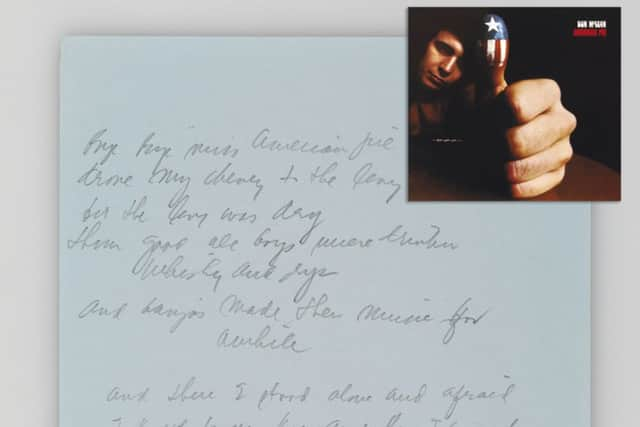

Hide AdLyrics are a crucial part of the musical experience for a lot of listeners, presumably including the person who paid £800,000 at Christie’s in New York on Tuesday for Don McLean’s original manuscript notes for American Pie. In the run-up to the auction, the singer-songwriter had promised that the true meaning of the song would become clear to the purchaser. I don’t think, however, that you need to be Don DeLillo to be able to work out that the song is broadly about a culture in decline, prompted by the death of Buddy Holly and the Big Bopper in an aeroplane crash that happened on “the day the music died”.

But how much do lyrics really matter to one’s enjoyment of music? Plenty of people will claim to love a song but don’t know any words beyond the chorus (witness pretty much any drunk man over 40 flailing around to Born to Run at karaoke and John Redwood’s horrifying attempt to mime the Welsh anthem will seem masterful, fluent and even sexy in comparison).

Bruce Springsteen’s oeuvre is bulging with examples of songs whose upbeat musical arrangement belies the solemnity of the lyrics. Ronald Reagan’s 1984 presidential campaign famously, and stupidly, pumped out Born in the USA in an effort to associate the candidate with that rousing, patriotic-sounding chorus. But even a cursory reading of the lyrics shows it is exactly the opposite: an indictment of a government that sacrificed its young men to horrific wars overseas, then discarded them when they returned home, broken and lost.

Springsteen is a master at smuggling social messages into enjoyable sounds. A spoonful of musical sugar helps that political medicine go down. It’s far more effective than being lectured at by an egotistical billionaire megastar.

I’ve heard it said that men and women consume music differently – that women start with the words and couldn’t tell you what instruments they hear, and that men focus on everything but the words – but I’m not at all sure about this. Anyone who really loves music will want to squeeze every last sound from it.

In a way I feel sorry for the download-only generation, most of whom will never experience the pleasure of saving up to buy a record or a CD, savouring the time spent getting to know its contents and studying the sleeve notes for the lyrics. Most of the time, when I was a teenager, I would get to know an artist by finding out what he or she had to say lyrically, then the layers of musical rewards would follow with each subsequent listen.

The lyrics of some of the musicians I love the most – Leonard Cohen, The National, Beck, Talking Heads, Simon and Garfunkel and Suede (when they’re not phoning it in) – stands alone as poetry, in my view. And then there’s the genius Kate Tempest, a young socially conscious poet who now makes music too. Her album, Everybody Down, is a proper, engaging story, told track by track. If you don’t listen to the words, you’re missing the whole point, I reckon.

And if you’re a proper fan, studying the lyrics of a musician you love is a romantic way of trying to understand what was going on in their heads during that time in their life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSometimes, however, it’s best to ignore what’s being said. Radiohead make music so sublime it shouldn’t be listened to if you have any significant decisions to make that day but, heavens to Betsy, the lyrics are hokum sometimes. Other songs are written to make you dance and engage your funk than rather than your brain, so the daftness of the words is neither here nor there. Look up the words to the Bee Gees’ Staying Alive. Utter tosh. As for Duran Duran’s Rio – “Cherry ice-cream smile, I suppose it’s very nice.” You what, Simon? It makes you wonder which lyrics didn’t make the cut. Remember Mmmbop, the catchy 1990s song by those blond teenage boys Hanson? You probably never even heard the lyrics in the verses, but buried in that jaunty pre-pubescent voice are words that look like a young goth’s cry for help on social media.

Then you’ve got lyrics that pose moral dilemmas. I confess to having a hard soft spot for classic gangster rap despite some truly nasty sexism in the words. And do you choose to ignore the words of Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams’s Blurred Lines, a musically great party song that has been banned from certain university campuses for making light of date rape? It’s tricky.

Pop songs about love are an altogether different game. They are largely written and performed to shift units and are consumed voraciously by young people looking for something to match their all-powerful emotions. What’s accompanies the voice hardly seems to matter, on the whole. The same goes for cheesy songs about loss and despair. Where would we be without those lyrics? How would inarticulate people express affection for each other without them? How else would the heartbroken and the drunk be able to sit in a crumpled heap and wail: “This song is about meeeeee”?

FOLLOW US

SCOTSMAN TABLET AND MOBILE APPS