Anna Burnside: The magic of the Mackintosh

There is a painting, somewhere in the Burnside family archives, by Anna aged around 12. It’s a view of the rooftops of Glasgow as seen from the Hen Run, the window-lined top floor of Glasgow School of Art. I went to drawing and painting classes there on Saturday mornings. Even though part of my childish self would rather have been watching Tiswas, walking up Mackintosh’s staircases, smelling the turps-impregnated floors, buying paper from the tiny shop in the basement, was thrilling in the extreme. The skyscape masterwork was chosen for the end-of-term exhibition and hung on the walls of what was then the main gallery space. If airpunching had been a thing in the 1970s, that’s what I would have done.

My mother was a student at GSA during the war. One of her best friends taught me, patiently and expertly, on those distant Saturday mornings. In subsequent years, when Mackintosh became Mockintosh and it was all too easy to sneer at the jewellery boxes and uPVC windows that bastardised his most recognisable motifs, it became my precious secret. I had experienced the real thing, seen how this entrancing building worked on an aesthetic and practical level. The man who designed Glasgow School of Art could never be naff, no matter how horrendous the earrings perpetrated in his name.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen American architect Steven Holl won the competition to design a companion piece on the opposite side of the road, to replace several GSA buildings which were very far from being world-class architectural treasures, his starting place was the Mack. His partner Chris McVoy – the hands-on presence during construction of what’s now called the Reid Building – told me: “Steven and I both studied the Glasgow School of Art building in college.”

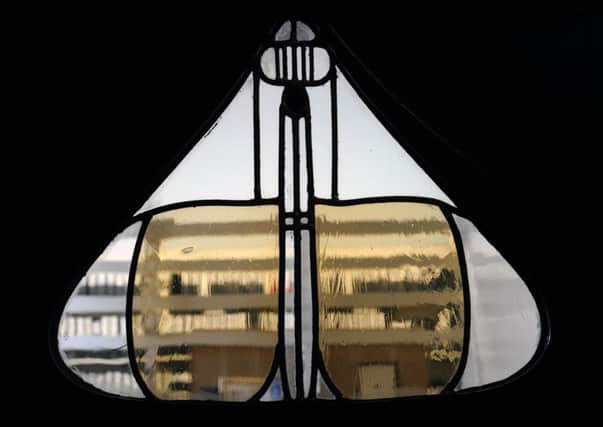

Both men decamped to Glasgow and spent hours in Renfrew Street, exploring how Mackintosh used 20 different varieties of light, before coming up with their concept for the Reid.

At the official opening of Holl and McVoy’s astonishing new building last month, I bumped into McVoy again. He was on his own, on Dalhousie Street, taking photographs of the eastern elevation. He was so happy: his astonishing new building was finished, it was full of students getting stuck into the free bar, it was holding its own opposite one of the most important structures of the 20th century.

I thought about McVoy on Friday evening, when I looked at that same street from behind the police cordon. The Reid Building, which had just been named by the Architects’ Journal the AJ100 Building of the Year, looked green and fresh, catching the late sun. The side of the Mack that is on Dalhousie Street itself also looked fine. But it was just a trick of perspective. The air was full of the sour smell of burning history. Occasional pieces of ash blew in the wind.

The visible flames had been dampened by the time I got to Sauchiehall Street. Watching that on television had been upsetting enough. My neighbour, a GSA graduate, texted to tell me it was on. His next message read: in tears.

My phone pinged again as soon as I got off the bus. “How does it look?” Smoke was still shooting upwards from the library windows on Scott Street. The odd lick of flame was visible at the very top of the building. Panes of glass were missing, others cracked, the frames black and dulled with soot. The roof had gone. There was police cordon tape sealing off a chunk of Garnethill, fire engines backed up round the corners, dirty water streaming down Scott Street.

I texted back: heartbreaking.

The corner of Scott and Sauchiehall streets, the spot that afforded the best view, was busy. Parents held up small boys: with no understanding of the architectural trauma unfolding, they were excited to see real-life Fireman Sams, expanding ladders and rows of shiny red engines. The occasional student, having been evacuated from the building earlier while putting the final touches to their end-of-year projects, stopped by for another look. Everyone’s priorities were different. “Oh no,” one male voice behind me said. “Gubbed,” agreed his friend. “It has kicked the bucket.” There was a pause. “More importantly, does this mean Campus will be closed tonight?”

In fact Campus, abutting the Scott Street end of GSA, was not closed. Teatime drinkers, their backs to the emergency services and Sky News live broadcasts on the pavement below, were visible through the windows. Further up Sauchiehall Street, the tables outside other bars were full. A bit of acrid smoke and the possible destruction of one of the most important parts of the city’s built environment does not put the Glaswegian off the post-work Friday pint.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA sometime colleague scooped me up and suggested something similar. We avoided the art students’ regular favourites – the Variety, the Griffin – fearing it would be like gate-crashing a wake. In a more anonymous establishment, we held our own memorial service.

He had no connections with the art school, had never been inside the building, had to perform a couple of mental Google searches before he could come up with the wife of an old friend who had been a student there. Architecture and contemporary art are not what get him out of bed in the morning. Yet he had felt compelled to come down, see for himself what was happening and take some photographs.

“You could smell the smoke in our office,” he told me, washing it from his throat with cold lager. “We were listening to the reports on the radio all afternoon. It was just a building I walked past. I don’t think I’d ever thought about it as much as I have done today.”

Until Friday, many Glaswegians felt the same. They knew it was great, and were hugely proud of it and delighted Americans and Japanese tourists come to see it, without feeling any pressing need to go and experience the space, still used as Mackintosh intended, for themselves.

That chance is now gone, for the foreseeable future at least, until some miracle of restoration is performed. Today the city is bruised, by the damage done to this neck-pricklingly wonderful building and by people kicking themselves that they did not go and stand in the library, smell the furniture, sit on it, wonder at those 20 different ways Mackintosh used light.

No matter how skilful and loving the reconstruction (and there is surely going to be one) it will have lost the patina of love and learning left by the generation of students, teachers, graduates and starstruck schoolgirls that went before.

For that chance, those memories and for that time I spent in that building, I am beyond grateful.«

Twitter: @MsABurnside