Andrew Wilson: Importance of character in politics

It is the dark times of crisis that tend to truly show the mettle of a person. And also the brightly lit times of elation, victory and success.

Just listen to the frustrations of Tommy Wright the new manager of St Johnstone FC whose brief flirtation with European success was brought to a cruel end in Perth on Thursday night. They lost a penalty shoot-out to Belarusians from Minsk. What hurt Wright was less the defeat itself but rather the behaviour in victory displayed by his vanquishers: “they lacked class”, he said, and indeed they appeared to. For proper sports people, this matters. And it should.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe spoke a human truth though. The opportunity for people to truly become great and display uncommon depths of character presents itself in both winning and losing. In the best sports clubs it is drummed into young minds as much as the importance of fitness. Character is all.

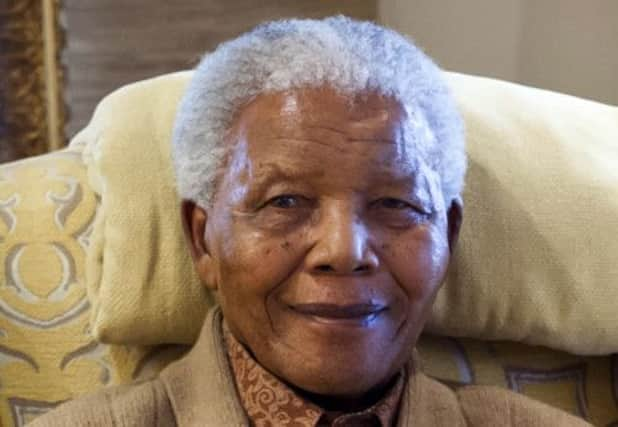

For me the two most striking political examples of the last century come are Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela. Their character will be recorded by history as among the most remarkable of any people of any time. They demonstrated almost an almost inhuman grace in both triumph and adversity.

There are many examples of this. Following the independence of India in 1947 at the height of his success and power Gandhi sought to offer the post of Prime Minister to the eventual leader of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, and a government led by the Muslim League. The act of munificence to a minority was an attempt to keep a unified India. It failed ultimately, but what an idea.

In 1994, following the victory of the ANC the focus of Mandela’s transitional government was the reconciliation and unity of a nation ripped asunder by Apartheid. Despite so many years of repression which could have justified that most human instinct, revenge, it was unity which inspired Mandela. He put it thus: “Resentment is like drinking poison and hoping it will kill your enemies”.

In our country the political tests and the victories are of a lesser scale. The stakes are lower but there is no need for the character of the actors to follow suit.

Possibly the greatest test of any political leader is therefore to unify behind progress. It is all too easy to seek the diversion of division in order to obtain and retain power rather than galvanise a country’s assets behind its betterment. The farcical behaviour of Ukip’s Godfrey Bloom MEP last week is a case in point.

Step forward also, I am sad to say, the columnist at our sister paper Michael Kelly, former Labour Lord Provost of the Glasgow City Council. Writing in The Scotsman, his basic thesis this week was that in the independence referendum “losers should lose” and that when “Yes loses, as it will”, it should lead to no progress for the powers of the Scottish Parliament or Scotland’s story despite overwhelming support for it. Worse in fact: “The dream consequence of this loss should be a steady erosion of Holyrood’s powers until it can be abolished”. He sought common cause with the Tories to rally behind him. I am unaware of them doing so. Perhaps even they have learned the lesson of history.

“So what?” You might say. “Kelly speaks for no-one but himself,” as many of the more thoughtful Labour thinkers told me this week when I asked for views on what he said. Maybe. But his argument certainly finds common cause with many across the “Brownite Centralist” tendency of both Labour and Tory politics in Scotland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhy else would there be no specific proposal on offer to date on what further Home Rule progress might look like? Why then were the Tory/Liberal government and Labour so keen to avoid a multi-option referendum that might run the risk of unifying the country behind the highest common denominator of progress?

Remember what they said then: “No consolation prize in defeat for Salmond”. Pretty close to Michael Kelly is it not? The priority it seems is to beat the man and his party rather than determine the best outcome for the future. Revealing on many levels. Kelly may represent a frank extreme but it is anchored in a belief held by many who should know better.

I draw two conclusions from this. The first is that if you are doubtful of the case for independence but want to see Scotland advance in stages then far better to vote Yes. Given the certainty of everyone from Kelly to the official leaders of the No Campaign that victory for them is certain – after all they assert that “it is not enough to win, we must win well” – then the larger the Yes vote the greater the chance that Scotland progresses.

The second is that there is some very substantial growing up to be done in the political culture of Scotland and among many of its main characters. Too often where character should be found, the behaviour, language and tone of many politicians of influence is found wanting. Maybe the electorate should determine to do something about that. «

Twitter: @AndrewWilsonAJW