Andrew Whitaker: Tories and Scottish Labour need rethink

Home Secretary Theresa May stated that the Tories were seen as the “nasty party” by many at their conference in 2002 at a time when Tony Blair’s New Labour was wiping the floor with the opposition.

Mrs May told her party to face up to the “uncomfortable truth” about the way it was sometimes perceived by the public, not long after high profile Tories such as Lord Archer and Jonathan Aitken had been jailed for perjury and perverting the course of justice.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHer coining of the “nasty party” phrase was a belated admission by one of the more astute Tory politicians, in a fairly weak line-up at the time, of the way large parts of the British electorate saw the Tories.

Back in 2002 when Mrs May uttered those words to annual conference in Bournemouth, then as chair, the party was seen as toxic by many voters, having just a year earlier slumped to a second crushing defeat at the hands of Labour.

The “nasty” tag was arguably deserved following the Major and Thatcher governments, spanning 18 years from 1979 to 1997, implementing policies such as the poll tax and opposing the minimum wage, as well as sleaze scandals involving former ministers such as Neil Hamilton who faced allegations over “cash for questions” in the Commons, still lingering in the memories of voters.

The Tories, upon finding themselves in opposition in the late 1990s, did not exactly go out of their way to detoxify themselves particularly when sections of their party, including Thatcher and former chancellor Norman Lamont, openly associated themselves with calls for the release of the former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet after his arrest and detention in London on a warrant from Spain requesting his extradition on murder charges.

Even after their first outright election win in 23 years, the party remains toxic in large parts of the UK, not least in Scotland where it has never managed to amass more than one MP at an election since 1992.

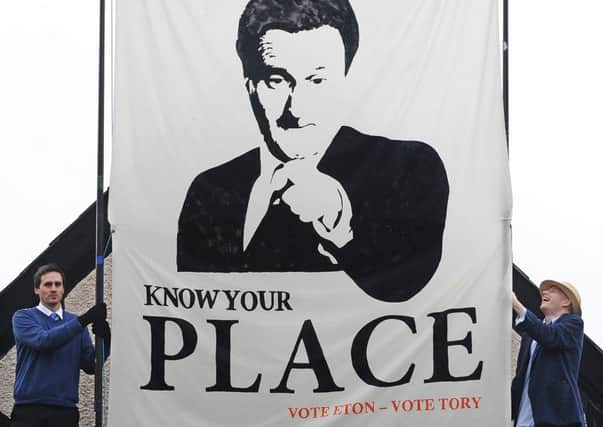

The heavy duty and non-stop austerity coming from David Cameron’s government and the negative way he and his close ally Chancellor George Osborne are perceived by some, suggests there is little chance of the Tory brand being detoxified any time soon.

Only the delusional would believe the Conservative party is actually loved or even liked by a majority of the electorate despite its shock and relatively decisive win at the general election in May.

The fact that Tory delegates to conference in Manchester this week have been advised not to wear their credentials for the gathering in public speaks volumes, as do the anti-austerity protests outside, on a scale not seen at the event since the Thatcher and Major years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut the ongoing toxicity issue for the Tories, coming at a time Labour’s new leader Jeremy Corbyn is pursuing a political direction never before seen within the party raises the question of what it is to be “nice” rather than “nasty” in politics. Scottish Labour has undoubtedly become a toxic brand too, having lost the right to be heard in the minds of many Scots, who have inflicted a series of heavy defeats on the party.

Although never a “nasty party”, Scottish Labour did allow itself to be portrayed as having a sense of entitlement to political rule in Scotland and of failing to embrace devolution fully.

There were also major political and moral miscalculations made by Scottish Labour that at best did not help with detoxification, such as a review of universal free services like free NHS prescriptions and talk of ending a “something for nothing” culture – words that allowed the SNP to accuse the Labour leadership of being Tory-lite.

Backing for knee-jerk and dog-whistle style polices such as mandatory jail terms for anyone caught carrying a knife, regardless of the circumstances, did not exactly help foster a progressive image for Scottish Labour.

But it’s Jeremy Corbyn who, without necessarily intending it, is perhaps showing Scottish Labour how to be nice again, with a new way of doing politics.

Perhaps Mr Corbyn has been helped by taking questions sent to him by the public into the Commons chamber and posing them to Mr Cameron, or even with the “idiosyncratic” images that appeared last weekend of him giving an impromptu speech to a hen party on a train.

There will be many people out there who perceive Mr Corbyn as a nice man who is attempting to do politics differently.

Perhaps many will have assorted disagreements with Mr Corbyn, but simply take the view that the Labour leader is at times unfairly pilloried by parts of the media and believe that he deserves a fair hearing – something that could yet help him out electorally.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne such example should be his refusal to get personal, something straight from the playbook of the late Tony Benn, who always sought to make an issue-driven point rather than indulge in personalised attacks.

Just lately the anti-politics candidates or anti-establishment figures have appeared in the guise of nationalism, whether it’s the anti-immigrant and anti-EU rhetoric of Nigel Farage’s Ukip or the nationalism of the SNP, which does not always accord with its self-styled and carefully choreographed image of a civic and social democratic party – to take the cybernats as just one example.

But with Mr Corbyn the platform is a clear anti-austerity one that perhaps even conjures up images of classic films roles, such as James Stewart as an inexperienced senator exposing corruption in the US Senate House and standing up for ordinary folk in Frank Capra’s Mr Smith Goes To Washington.

Perhaps less flatteringly there is also Being There, the last film featuring Peter Sellers to be released in the actor’s lifetime, as a humble gardener called Chance who ends up being viewed as a political sage after his accidental remarks to a US senator about the garden are interpreted as astute economic and political advice, taking him to national public prominence.

Kezia Dugdale is already showing signs that she gets that Scottish Labour is in a battle for its very survival as a political force, knowing that her party has to come up with answers to the popularity of Nicola Sturgeon, something the unlikely rise of Mr Corbyn may yet offer some ideas on.