Andrew Whitaker: Labour could learn from Robin Cook

The late Robin Cook is with good reason viewed as one of the giants from Labour’s post-1997 13-year stint in UK government and sits alongside Tony Blair and Gordon Brown as being a major player from that era.

Cook is viewed in high esteem in part due to his championing as the foreign secretary of an “ethical foreign policy”, which he launched just days into office with a pledge to “put human rights at the heart of our foreign policy”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis much admired status in Labour circles more than a decade after his death also owes a great deal to him quitting the Cabinet on a point of principle over the last Iraq war in 2003.

Cook’s talk of how a “fundamental principle of Labour’s foreign policy has been violated” by backing a “war with neither international agreement nor domestic support” was a devastating critique of Blair’s decision to join George W Bush in the US-led military invasion of Iraq.

But what is perhaps forgotten about Cook is that the former Livingston MP was arguably Labour’s most effective opposition politician from the late 1980s through to the mid-1990s.

Despite the obvious lack of figures of Cook’s calibre now in Scottish Labour’s ranks, looking at the late politician’s time in opposition could be of real help to Kezia Dugdale’s party.

Cook shone most brightly between 1992 and 1997, the final term of 18 years of Tory rule, with an uncompromising approach to taking on his opponents, that has huge lessons for Scottish Labour if the party is to establish itself as a credible and competent opposition to the SNP.

Cook was brutally effective in demolishing the Conservative government of John Major, when numerous ministers were criticised in the Scott inquiry into the sale of arms to Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq.

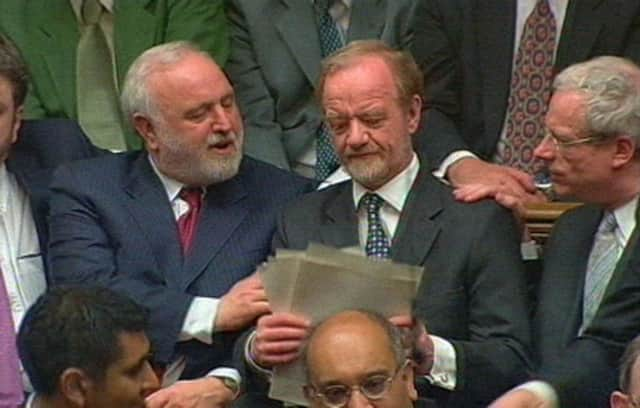

Despite being given just two hours to read a 2,000-page report into the inquiry, Cook would demolish Tory ministers criticised in the report from February 1996, stating in the Commons: “This is not just a government that does not know how to accept blame – this is a government that knows no shame.”

Likewise soon after the 1992 general election when the then president of the board of trade Michael Heseltine unveiled plans to shut a third of Britain’s deep coal mines, Cook was credited with being a powerful voice in opposing what many saw as unnecessary butchery by a recently re-elected Tory government hellbent on taking crude revenge on an old enemy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut it was in the election of 1992 that Cook had one of the most bruising episodes of his political career, in what was to become known as the “War of Jennifer’s Ear”.

Cook, then Neil Kinnock’s shadow health secretary, had been one of Labour’s stars in the 1987 to 1992 parliament, when Tory unpopularity owed much to the government’s polices on the NHS, which many voters viewed as partial privatisation.

In late March 1992, Cook was linked to a no-holds-barred broadcast that attacked Tory health policy based on the experience of a five-year-old girl called Jennifer, who had been waiting a year for a simple operation on her ear.

It was contrasted with that of a child of a similar age whose parents were able to afford private treatment.

The polemical-style broadcast was inspired by a letter sent to Cook, from Jennifer’s father, about the severe delays his daughter faced.

But it later emerged that the mother and grandfather of Jennifer were Tory supporters, with Cook finding himself accused of using a child to make political capital.

Some commentators suggested the row helped derail Labour’s campaign ahead of an election that the party unexpectedly lost to the Tories.

But a close ally of Cook at the time, the Labour MP Derek Fatchett, who would go on to serve as his deputy in the foreign office, before dying of a heart attack in 1999 – later commented that Cook’s approach in taking on the Tories over the NHS had been lacking from Kinnock and was the right response to the “scare campaign” the Tories ran to great effect in 1992.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s here that Cook’s wisdom has real lessons for Dugdale and Scottish Labour, even though the party in Scotland is not within a chance of an election win as it had been at UK-level in April 1992.

When we talk of negative political campaigning we often think of aggressive American-style TV adverts, the like of which the US public will almost certainly be force-fed in the coming months as Donald Trump’s camp make outrageous barbs about his Democrat opponent.

But Cook knew how “to go negative positively”.

To have a campaign against Tory privatisation of the NHS that is still talked about 24 years later, and to be remembered for a forensic demolition of Tory ministers over arms sales, is not something that happens to every MP.

Dugdale’s current line of attack that accuses the SNP of “lining up beside the Scottish Tories” to oppose tax rises for the wealthiest could yet turn out to be an effective approach.

While Dugdale has had difficulties over what opponents said was a back-tracking in support for an income tax rebate for the less well off, the SNP have been strikingly timid when it comes to committing to higher taxes for the wealthy.

There is a strong case for doing what Cook did to great effect by challenging the SNP to commit to reverse Tory welfare cuts when new powers arrive at Holyrood.

Of course Cook’s opponents were a Tory party that, despite its re-election in 1992, was largely disliked, whereas Dugdale is up against a different beast that appears to be able to attract support regardless of its performance in government.

An SNP landslide looks likely on 5 May, but adopting Cook’s approach could at least allow Labour to shine in the campaign and emerge as a strong opposition ready to expose perceived Nationalist weaknesses.