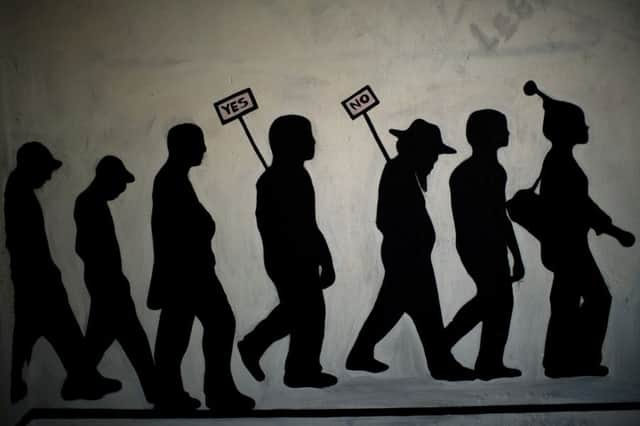

Analysis: Tsipras could still lose if No side wins

WHETHER Greeks decide in today’s referendum to accept their lenders’ bailout deal or reject it, the government’s hold on power may be shakier than its brash prime minister has calculated, analysts say.

Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras is banking on fellow Greeks to deliver a resounding “No” in the popular vote that he believes will give him strong leverage in his negotiations with creditors to swing a softer bailout deal for a country ravaged by years of harsh austerity, deep recession and crushing poverty.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA win for the No campaign, the reasoning goes, could also furnish Tsipras with an endorsement for his five-month rule and allow his government to consolidate – and extend – its grip on power.

That may not be the case, analysts say, since a No vote could still plunge Tsipras’s position into uncertainty if negotiations drag on with lenders, who would see such an outcome as a Greek snub of the euro. Without a quick deal, banks could stay shut to stop reserves running dry.

“A deteriorating import-dependent economy will provoke a rapid decline in public support for the government and fresh elections may become inevitable, but this will take time,” said Dimitri Sotiropoulos, political science professor at the University of Athens.

A win for the Yes campaign could cast Tsipras’s public mandate in doubt and force him to broaden his coalition government, political analyst George Sefertzis said.

Tsipras’s radical left Syriza party emerged from the political fringes in January as Greek voters sought an alternative to what they saw as a bankrupt political establishment they blame for opening the door to half a decade of punishing salary and pension rollbacks, steep job cuts and hefty taxes.

Just a few years ago, the country’s two main political forces – the right-wing New Democracy and the socialist PASOK parties – commanded some 80 per cent of the vote between them. Now, with many Greeks seeing them as kowtowing to the lenders’ diktats, their support was dwindled.

Tsipras’s youth, unorthodox style and pledges to fight the good fight for the country’s poorest endeared him to many and persuaded some that he could take on the institutional behemoths that decide the economic fate of entire nations.

But months of talks without real results have eroded the Greek government’s credibility in the eyes of Europe’s power circles.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“This government doesn’t trust the institutions of the EU and the IMF, and those institutions trust the Greek government even less,” said Sotiropoulos.

Tsipras’s gambit appears to rest on whether he can clinch a deal quickly so that banks can reopen and get money flowing to businesses again. Tsipras told private TV station Antenna on Thursday that he sees a deal with creditors emerging “within 48 hours” after the referendum.

But Greece’s creditors – the EU and the IMF – are unlikely to cave in on demands for tough austerity measures, said Sotiropoulos.

The latest opinion polls put the No and Yes camps in a dead heat, as divisions have emerged even within the Greek government.