Allan Massie: We are all middle-class nowadays

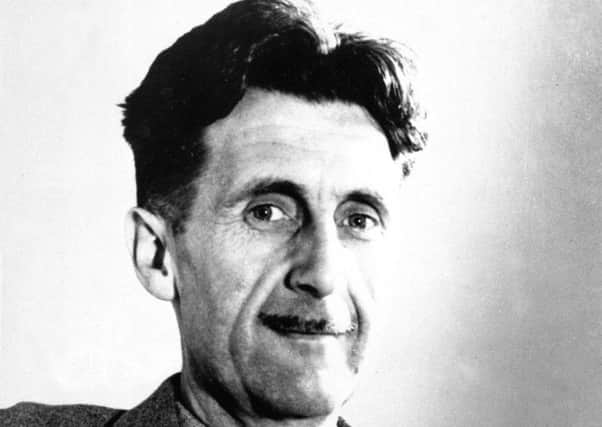

In 1941, in an essay entitled England Your England, George Orwell wrote: “One of the most important developments in England during the past 20 years has been the upward and downward extension of the middle class. It has happened on such a scale as to make the old classification of society into capitalists, proletarians and petit-bourgeois (small property-owners) almost obsolete.” He went on to remark that “after 1918, there began to appear something that had never existed in England before: people of indeterminate social class”.

The process has continued ever since – in Scotland as well as England. Of course, it is true that we are all middle-class now, and many people who lead recognisably middle-class lives may still choose to describe themselves as working-class.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNevertheless, the sharp and clearly delineated class structure that used to be evident has at the very least become blurred. There are still poor people, some of them very poor, who have been left behind as over the decades we have, despite a few blips, become a steadily richer and more prosperous society.

And there are many who may earn less than we think they should earn, but who nevertheless live in a style that is not different in kind, though it may be different in degree, from that of people who would describe themselves as middle-class.

It is sometimes asserted that social mobility, which was a feature of Britain in the decades after the 1939-45 war, has now stalled. Certainly, there are people living in certain sectors of society who may have little prospect of improving their lot.

They suffer from poor education and are trapped in dependency. They are sometimes described – disagreeably described – as an underclass, and though some determined individuals may manage to escape from it, too many are unable to do so. They may amount to between 5 and 10 per cent of the population.

Some years ago the Guardian journalist Polly Toynbee compared the process that we call “social exclusion” to a desert crossing in which a minority of the caravan are falling ever further behind the main group. It is, I think, indisputable that this is happening, and no government whether employing the carrot of benefits and tax credits or the stick of tough welfare reform has managed to help those falling behind to catch up with the main body of the caravan.

Yet in other respects it is perfectly obvious that social mobility has not stalled. The gap between the really rich and the rest of us is undoubtedly wider than it has been for a long time. Yet even many of the rich are not the old rich but people who have broken through what has become a flimsy and easily penetrated barrier.

There are for example a good many very successful businessmen – and businesswomen – whose parents or grandparents, or great-grandparents came here as poor immigrants from Italy or eastern Europe or the Indian subcontinent. Obstacles of prejudice and discrimination that used to hold such people back either no longer exist or are very much weaker than they were.

In like manner, Scottish Catholics used to suffer discrimination in both the workplace and society at large. This is now largely a thing of the past and, consequently, there is a large and still growing Catholic middle-class. This is a significant example of social mobility.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA university education used to be a privilege enjoyed by the few even though 60 years ago, when less than 10 per cent of young people went to university, there were a good many sons – and even more daughters – of the middle-class who went straight into jobs after leaving school or, in the case of boys, having done their National Service. Any professional qualification they required would be obtained by attendance at night classes.

Now something in the region of 50 per cent of school-leavers go on to higher education. The expansion of universities has been remarkable, and undoubtedly promotes social mobility. People with a university degree may still, for reasons of family loyalty or origins, choose to describe themselves as working-class, but the way they live, eventually in most cases, in a house or flat which they have bought, is evidently very different from the working-class life of their parents or grandparents. After all, I believe that loyalty to his origins leads Sir Alex Ferguson to call himself working-class, but you didn’t find many racehorse owners or collectors of fine wines in the Govan of his youth.

Orwell, himself a socialist and rebel against the class into which he was born, and in which he was reared (educated at Eton), nevertheless recognised that “the tendency of advanced capitalism has therefore been to enlarge the middle class and not to wipe it out, as it once seemed likely to do”.

Today, capitalism has the same effect because a modern economy can’t flourish without, as Orwell put it, “great numbers of managers, salesmen, engineers, chemists and technicians of all kinds” who “in turn call into being a professional class of doctors, lawyers, teachers, artists etc”.

This process has continued, despite recurrent slumps and recessions. The middle-class just keeps growing, and even many who lag behind benefit. “However unjustly society is organised,” he wrote, “certain technical advances are bound to benefit the whole community”, and this is every bit as true now as it was when Orwell remarked on it in 1941. The rich get richer, but so do a lot of other people. The gap between the very rich and the rest of us may be wider – is indeed wider – but this doesn’t mean that most of us are not ourselves getting richer.

There is a problem – a social, economic and personal problem – with those who are left behind, and none of us knows how to address this, though improved schools still seem the necessary first step. But, to give Orwell the last word (which he often deserves): “A person who has grown up in a council housing estate is likely to be – indeed visibly is – more middle-class in outlook than a person who has grown up in a slum.”