Allan Massie: Gordon Brown’s dual formula

One word has been strangely absent from the independence debate. I don’t think Alistair Darling uttered it once on Monday night. He talked a lot about the United Kingdom, and the strength and security it offers Scotland.

But, unless I missed it, he didn’t speak of being British as well as Scottish. And yet for a great many Scots, being British matters. I would guess that a majority of those who will vote No on 18 September will do so because they value that part of their identity which is British. Many of us are comfortable with a dual identity, Scottish and British, and indeed with a triple one, being also European. But somehow or other, amidst all the argy-bargy about the currency and so on, this consideration has all but slipped out of sight.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

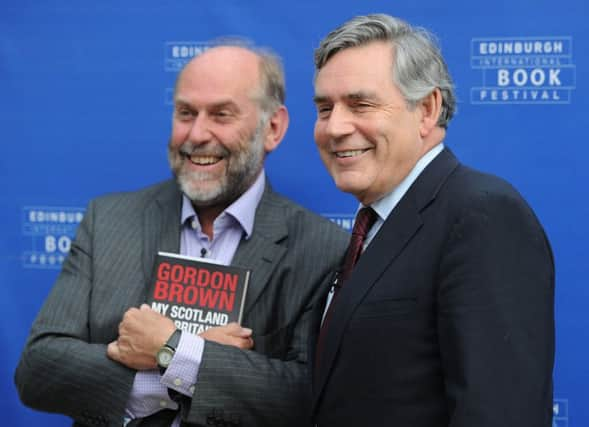

Hide AdIt is not quite true that all the politicians have been avoiding the word. Gordon Brown, whose resurgence has been one of the happiest and most welcome features of the campaign, has spoken of what being British means to him.

He can do so confidently, in part because nobody can credibly question his Scottishness or his love for, and attachment to, Scotland. His book My Scotland, Our Britain is outstandingly good, and it makes the Unionist case better than anything else written or said in this long, drawn-out campaign. It makes it positively, and his insistence on Scotland’s contribution to the making and development of Britain and British values is a rebuke to the narrow, defensive nationalism of the SNP.

When he concludes by saying that he wants Scotland to lead Britain, not leave it, he invites us to open our eyes to the possibility of a better and more generous future.

The future of the NHS has become a subject for heated debate with the Yes campaign raising the question of creeping privatisation. Since responsibility for the NHS has always been devolved, first, to the Scottish Office and then, since 1999, to the Scottish Parliament. Gordon Brown is right when he says that only the Scottish Government could, if it chose to, privatise NHS Scotland.

However, setting aside arguments about whether the introduction of private contractors matters as long as the NHS remains free at the point of use, it’s worth looking at the circumstances in which it came into being, along with the welfare state as we know it.

They were the creation of the reforming Labour government of 1945-51. That government was unusual in one significant respect. Though the Labour Party itself was, to a great extent, created and developed by Scots, notably Keir Hardie and Ramsay MacDonald, the Attlee Cabinet was remarkable for the absence of Scots.

Indeed, with the wartime Secretary of State, Tom Johnston, having left party politics to become the first chairman of the North of Scotland Hydro-Electric Board, Attlee had some difficulty finding a Scottish Labour MP sufficiently competent to be Secretary of State for Scotland (He eventually settled on a decent but dim figure, Arthur Woodburn). So, whereas Scottish MPs have been well-represented in most Labour governments, even to the extent of dominating the recent Blair-Brown ones, the NHS, which is now so fiercely defended, was the creation of a Welsh Minister of Health, Aneurin Bevan, and a mostly English Cabinet.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFrom the first, NHS Scotland was administered by the Scottish Office mandarins in Edinburgh, but it was and is a British institution.

The welfare state has its origins in the Liberal government of 1906-14 but owes its present form to the Beveridge Report of 1942. William Beveridge was a child of the Raj, his father being a judge in the Indian Civil Service. The father was born in Dunfermline and there was a strong streak of Scots Presbyterianism in William Beveridge, who was a liberal, not a socialist. Still, it was the Labour government that enacted his report which had recommended a system of compulsory National Insurance to eradicate the “Five Giant Evils” which he identified as “Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness”. So the welfare state – a term Beveridge himself disliked – came into being: a British, not Scottish, creation. One might remark that, on the evidence of Beveridge’s own thoughts, he might have approved of at least some of the reforms of the welfare system now being made by the coalition government. His identification of ignorance and idleness as two of his Giant Evils was very much in tune with his Scots Presbyterian upbringing. Nothing remarkable about that; who among us is in favour of ignorance and idleness?

The point I am making is that what Alex Salmond claims as a reason for the necessity of independence is not peculiarly Scottish but British. We are what we are in part because of our experience of 300 years of the Union. Alex Salmond is as much a child of the British experience as Gordon Brown or Alistair Darling or the Scottish Tory leader Ruth Davidson. Disliking this, he advocates surgery. He would cut us off from our past as surely as from the other nations and national groups in the United Kingdom. This is unnecessary and would be painful, especially so for the millions comfortable in their dual Scottish-British identity.

There is a better way forward – working in harmony with the other members of the British family. In the last chapter of his book, Gordon Brown offers ten proposals for further devolution and the reform of the Union. They are all eminently sensible. “The choice,” he writes, “is not between being Scottish and being British: we are both and can continue to be both.”

“We are better able than most,” he says, speaking with the authority which derives from his own experience, “to rise to the challenge of showing how nations with long histories, distinctive identities, separate institutions and proud cultures can work together in an age of interdependence”. Can anyone of sense and goodwill dispute this?