Alexander McCall Smith: The risk to authors under new Scottish hate crime law

It is not entirely new, and has been simmering away for some time, in the background, over university de-platforming of unpopular speakers. Now it is full flood with the conclusion of the consultation period over the Scottish Government’s proposed extension of criminal law protection for new groups, including the elderly. The Scottish Government’s legislation is clearly well-intentioned, but has attracted vociferous criticism from a wide range of public bodies, including the Law Society of Scotland and the police – neither of these being known for a tendency to cry wolf. It will be interesting to see whether the Government heeds these expressions of concern. It definitely means well here – and deserve credit for indicating its firm rejection of stirring up hatred. But the use of the criminal law to control the expression of views involves a delicate balance if the law is not to become repressive.

Authors are affected by this, as are those who possess books and are in the habit of passing them on to others. Speech amongst friends will also constitute a communication for purposes of this legislation. An ageist remark, uttered innocently and without intention to stir up hatred against old people, may be the subject of criminal investigation if the person to whom it is addressed is offended and makes a complaint. Of course, one would hope that restraint will be shown in the application of the legislation, but what if the police and prosecution authorities feel compelled by public outcry to respond to an unjustified complaint? The legislation provides for defences based on reasonableness, but the damage may be done well before that stage if a person who has no intention to stir up ill-feeling is subjected to investigation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

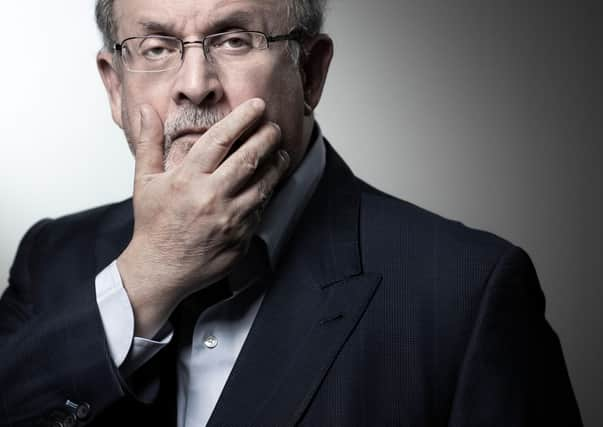

Hide AdEven in the second half of the twentieth century, authors have been accustomed to the powers that be telling them what they can or cannot write. The publishers of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, a work of charming innocence by today’s standards, eventually won a legal battle to bring the novel to the public. The same publishers entered the fray again with the Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, with the author himself being driven into hiding. Graham Greene was another victim: he incurred the disapproval of Papa Doc Duvalier for his portrayal of life under dictatorship in Haiti. There are countless other examples of writers who have struggled against the censorship of repressive regimes such as the former Soviet Union and its satellite states, or of various right-wing dictatorships. Suppression of freedom of speech, and even freedom of belief, is something that both right and left are capable of doing with equal enthusiasm.

Our current debate in Scotland is a bit different. The legislation here is aimed at stopping people from abusing or threatening others – and that is by no means the same as outright political censorship. Nobody should be allowed to intimidate others or insult them in such a way as to cause real distress and hurt. That is the equivalent of a physical assault – indeed it is often worse. If the criminal law tackles that, it is just doing its job of protecting the vulnerable. The issue, though, is the nature of the offence caused and, in particular, the extension of the law to include the punishing of those who did not intend to stir up ill-feeling of any sort.

For authors, these changes may put a question mark over fiction itself. Characters in fiction are the creation of their authors but are not the same things as the authors themselves. That may sound trite, but it is a point that needs to be made. The artistic work may also be viewed as something separate from its creator. Wagner stands accused of anti-Semitic attitudes, but should that prevent the performance or appreciation of his music? Regretting the wrongs of the past and indeed apologising for them (in deeds and words) is entirely laudable, but obliterating that past and its creations is another matter altogether.

Fiction will inevitably give offence to somebody, unless it is exceptionally bland. When an author creates a character, she or he may need to describe that character’s attitudes through dialogue. That means that the character will have to say something. Nice characters will say nice things that should cause no offence to anybody, but nasty characters – and fiction must have at least some of those – may say nasty things. That is because fiction often sets out to paint a realistic picture of how people are and how they behave. If these things cause offence to some readers, then those who take offence may argue that the book is liable to stir up hatred against a protected group of people – even if that was not the author’s intention. That is where the police come in.

The difficulty is that there are people who do not appear to appreciate that the views expressed by fictional characters may differ from the views held by the author. You may think that unlikely, but I suspect that most authors will be able to recount incidents where they have been blamed for what their characters do or think. Some years ago, I include in my Scotland Street series of novels a scene in which Bruce, an oleaginous narcissistic, makes disparaging remarks about his home town (discretion and fear of prosecution requires it not to be named here). That’s the sort of person Bruce is: he’s prepared to look down his nose on his own home town – a charming place with its Hydro and its surrounding Perthshire hills. My own feelings for the town in question are unreservedly warm, but Bruce’s remarks were attributed to me and I was hauled over the coals for expressing views that I certainly never held. One local politician suggested that I be required to visit the town and publicly apologise.

That was a case of over-sensitivity, but the point is this: any legal restraint on what authors can write must be very carefully calibrated, because there are those who will claim offence only too readily and will seek to shut down voices they may not like. The Scottish Government is right to protect people from abuse, discrimination and hatred. They deserve credit for that. But they must also protect artistic and intellectual freedom.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.