Alastair Dalton: Maps make a welcome return

For some, they’re beautiful and fascinating artworks which could be pored over for hours, and as satisfying as a good book.

But for others, paper maps are impenetrable and confusing irrelevances in the age of the satnav.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYou might think the simple pleasure of studying a map to inspire a next trip was a dying pastime, when you can instantly find your way from pretty much any A to B in the world on your mobile phone.

In fact, just as book sales have bounced back after the rise of ebooks, so have those of paper maps.

It has even prompted the doyen of map-making, the Ordnance Survey (OS), to relaunch a deleted series of maps after a gap of seven years.

This comes against a backdrop of the UK Government-owned firm turning round a ten-year decline in paper map sales, whose subsequent growth over the last two years has accelerated from 3 per cent to 10 per cent.

The success of the relaunched maps, which were shelved because of the overall sales slump, is also surprising because, in a way, they are very old fashioned in format.

The OS Road series are road maps, but not as you know it. In contrast to the maps you may associate with the OS, such as those used by walkers, these are relatively small scale (1cm to 2.5km, or 1 inch to four miles), with Scotland covered by just three sheets.

For me, there’s a place for both paper maps and satnavs, but I couldn’t see the point of this type, being too small to navigate any built-up area, and of an unwieldy size to grapple with in the confines of a car.

However, the OS tells me there have been “remarkable” early sales, which have been available for less than two weeks, with 500 bought on the first day.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe firm says their attraction is all about the popularity of spreading a map out and planning a jaunt, with these ones providing a “bird’s eye” view to show the bigger picture.

From that perspective, I can now see the appeal, and motorists lured by the clever rebranding of a northern circuit of Scotland as the North Coast 500 can see at a glance what they’re in for - and arguably the even more exciting roads that have been left out.

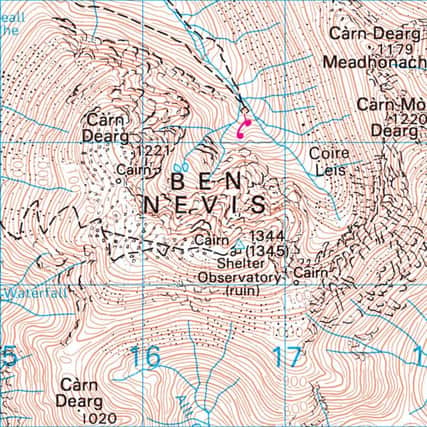

The maps also make you realise how much detailed they contain - which you may either be drawn to or seek to avoid - such as wind farms, mountain contours and sandy beaches.

It’s all the more heartening to see the Hebrides displayed full scale, and not in an inset box like on many other road maps.

A pity then that Orkney and Shetland are shown cramped at only about half the scale of the rest of Scotland, which does them and visitors to the Northern Isles a great disservice.

The OS is arguably yet another great Scottish invention, having had its origins in the government’s need to map the country following the 1745 Jacobite rising.

The Board of Ordnance - a predecessor of the Ministry of Defence - ordered a cartographic survey by Carluke-born William Roy to help open up the Highlands, with the map later extended to cover the whole of Britain.

Most of the OS’s income now comes from electronic maps, with such data used in most satnavs and online atlases such as Google Maps.

However, it can only be good for Scotland that there’s renewed popular interest in paper maps amid the explosion of digital rivals.