Afghanistan withdrawal: Most abject surrender in diplomatic history shows why UK needs to be more like France on military and foreign affairs – Professor Tim Willasey-Wilsey

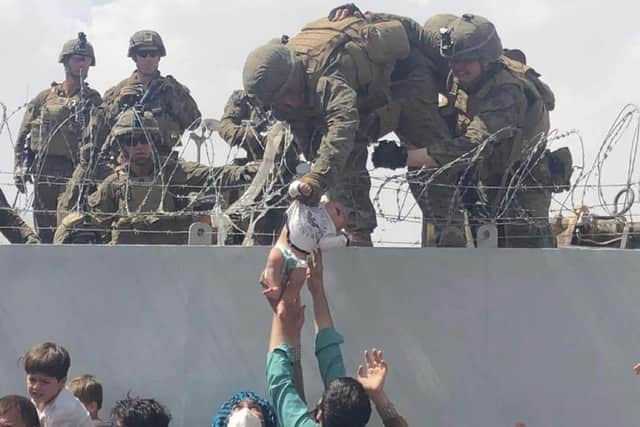

The United States should rightly shoulder the bulk of opprobrium for the events we witnessed this time last year; civilians falling to their deaths from C-17 transport planes, refugees standing waist-deep in sewage ditches, carnage as a bomb ripped through the crowd, and panic as thousands of people realised they were being left behind.

Later there was the realisation that a drone strike on suspected Islamic State (IS) terrorists had killed an innocent family. Left behind were billions of dollars of military equipment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe roots of this mayhem lay in President Trump’s desire to get out of Afghanistan after 20 years of ‘forever war’. That wish, which President Biden later shared, was entirely understandable.

What was not acceptable was the craven diplomatic negotiation which US Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad conducted with a Taliban delegation which included members of the terrorist Haqqani organisation behind the backs of the Afghan government.

That resulted in the Doha Agreement, possibly the most abject surrender document in diplomatic history. At least Munich in 1938 bought the UK a vital extra year to rearm without which it would have lost the Battle of Britain in 1940 and thus the Second World War.

There is no scope for the UK to feel satisfied with its role in the Afghan exit. The House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee focussed rather narrowly on the failures of leadership and on the maladministration of the refugee programme which was, and still is, shambolic.

However there were five other serious mistakes and oversights in Whitehall.

Government did not assess the effects of the withdrawal on its own Asia policy. Only five months earlier the Integrated Review (IR) had been published stressing the importance of the Indo-Pacific for Britain’s post-Brexit future.

In particular, a newly dynamic relationship with India was seen as a major objective. Afghanistan really matters to India – we should have known this from 19th Century history) – and so the withdrawal looked like a reduction in UK’s regional interest. The UK will be of less value to India because we are no longer on the ground in Afghanistan.

Little thought was given to the impact on wider foreign policy. No one seems to have asked the question: “What conclusions will China, Russia, Iran and North Korea draw from the withdrawal?” Putin’s attack on Ukraine doubtless owed much to a Kremlin view that the West had lost the will to defend its interests and its allies. China was undoubtedly relieved to see the West depart from a region contiguous to its troubled province of Xinjiang.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

Insufficient thought was given to the effects on UK’s independent counter terrorist (CT) requirements. CT was the major justification for the UK being in Afghanistan since 9/11.

Somebody should have asked the question: “How are we going to monitor Isis and Al-Qaeda once we have lost our foothold in Afghanistan?” Neither the Central Asian Republics nor Pakistan were willing to provide bases. The killing of the Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri confirms that the terrorists have returned to Afghanistan and that only the US has the reach to operate there, albeit at the very extremity of their reach.

The UK was never going to be able to change Biden’s mind but Whitehall should have considered a diplomatic solution with regional countries, all of which wanted to see a broad-based government in Kabul which included, but was not dominated by, the Taliban.

China, Russia, Iran, India, Turkey and the Central Asian Republics all shared this view. Only Pakistan wanted a purely Taliban government, but pretended otherwise. So there was a unique opportunity for a regional solution. The US briefly toyed with the idea of an Istanbul conference but their priority was to get out quickly.

Finally Whitehall did not challenge the Pentagon’s exit plan which was so evidently flawed and did not take into account a sudden collapse in Afghan army morale and which left the Taliban with a considerable arsenal of weapons, vehicles and even helicopters.

It is hard to escape the conclusion that Whitehall was asleep at the wheel. There are multiple mitigating circumstances. Covid and working from home certainly did not help.

Furthermore Afghanistan was seen as a legacy issue and organisational change (such as the integration of the Department for International Development into the former Foreign and Commonwealth Office) was proving difficult and was consuming a great deal of bandwidth. The four C’s of climate, cyber, China and Covid were the areas where talented staff wanted to work and contribute their creative ideas.

But there has long been a tendency in Whitehall to assume that the United States can be relied on to look after the UK’s interests.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe big lesson from the Kabul fiasco is that Britain needs to lean less heavily on a US ally which understandably has its own priorities. The UK needs to do its own thinking about its own interests and to ensure that it has the hard-power tools – both military and diplomatic – to deliver its own policies. France has taken this approach for decades but for the UK it will require significant change to diplomatic culture and to military capabilities.

Tim Willasey-Wilsey is visiting professor at King’s College, London, and a senior associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI). He is a former senior British diplomat

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.