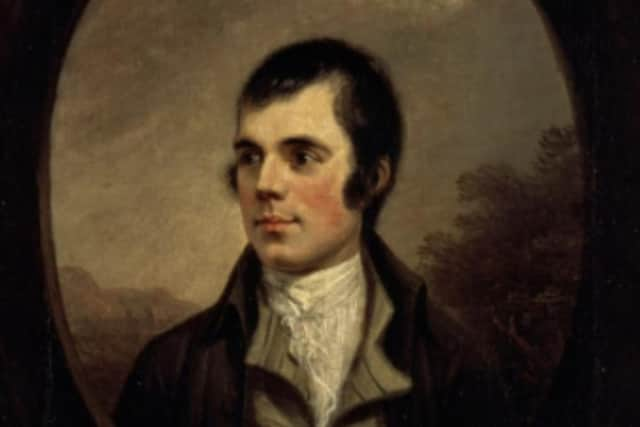

Burns Night: Is it time to gag Scotland's most famous poet Robert Burns

Burns is an easy target for revisionist hawks, not least because there is an annual drinking session in his honour. For many, Burns endures as a picaresque figure, a cad, and a bit of a bounder with a penchant for drink. England has no Shakespeare Suppers nor Italy Dante Dinners, whereas Burns is first among equals every January.

Burns had an eye for the ladies, but he was also among Scotland’s first pioneers of social commentary. The question now is whether, after over 200 years, his well-documented personal defects warrant the dismissal of his oeuvre and celebration.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is a common thread throughout Burns’ life to be moved by the plight of those less fortunate. In his poem The Rights of Women, published in 1792, Burns declared, “While Europe's eye is fix’d on mighty thing...The Rights of Woman merit some attention.”

The song For a’ That and a’ That, published in 1795, is one of Burns’ more famous egalitarian songs. He castigates love of rank, money and “tinsel” and extolls “The honest man, tho’ e’er sae poor, Is king o’ men for a’ that.”

Inspired by the French Revolution, the poem ends with a universal brotherhood prediction: “Then let us pray that come it may, It's coming yet, for a' that, That man to man, the warld o'er, Shall brothers be for a' that.”

Burns was from the romantic era but cannot be boxed in as a romantic writer and lyricist. He had idealistic and polemical skills matched by a fiery intolerance of injustice. Burns, after all, died wretchedly poor, in debt, and shunned and neglected. His relatability is among the chief reasons he has endured in the hearts of Scots.

Burns hated pomp, circumstance, hypocrisy and fundamentalists and, while he was a Scottish patriot, he was no parochial nationalist or jingoistic militarist. In his 1794 epigram, Thanksgiving For A National Victory, Burns rails against celebrating a naval battle in the early stages of the French Revolution: “Ye hypocrites! are these your pranks? To murder men and give God thanks!”

But the merit of Burns’ work is fast becoming second fiddle to the broader discussions about his character and personal life. Poet and playwright Liz Lochhead called Burns a “sex pest” and compared him to disgraced movie producer Harvey Weinstein.

In 1780 he established the Tarbolton Bachelor's Club with his brother and an assortment of other young men. The club was founded as a “diversion to relieve the wearied man worn down by the necessary labours of life”. Its constitution was unambiguous: “Every man proper for a member of this Society, must have a frank, honest, open heart… and must be a professed lover of one or more of the female sex.”

Unsurprisingly, Burns was elected its first president at age 21. But rake to rapist is the accusation against him now, and it risks the cancellation of his work without an analysis of the man’s own words weighed up against the facts of his life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBefore his death at 37, Burns had fathered 12 offspring by four mothers. He had at least four illegitimate children born to women who worked in service. Elizabeth Paton, who worked on the Burns family farm, had a “plain face, but good figure”. He spurned her, and Burns was later forced to apologise in church for his behaviour formally.

By 1788 Burns bragged to a friend of giving his pregnant lover Jean Armour a “thundering scalade [a military attack] that electrified the very marrow of her bones”. Furthermore, Burns said he “f****d her until she rejoiced” on a horse manure-strewn floor.

Robert Crawford, the author of The Bard, quotes the letter, arguing that “what he presents as… exclamations of pleasure may well have been cries of pain”.

Another servant, Jenny Clow, gave birth to another of Burns’ illegitimate children after an encounter in Edinburgh. She had been delivering a love letter between Burns and her employer, Agnes Maclehose (with whom Burns was having an affair). At the same time, Armour was pregnant with twins.

Three years later, Clow was dying, and Maclehose wrote to Burns: “You have now an opportunity to evince you indeed possess those fine feelings you have delineated, so as to claim the just admiration of your country.”

Burns sent her five shillings, and some accounts suggest he went to see her and offered a further undisclosed sum, writing her predicament made his “heart weep blood”.

Burns scholars, such as Gerard Carruthers, said there was “no good evidence” that the Scottish bard was a rapist. Wilson Ogilvie, a former president of the Burns Federation, acknowledged that “Burns was not lily-white in his attitudes towards women”.

Women are one of many problems for Burns. Despite later writing about “the unfeeling selfishness of the Oppressor” and producing the distinctly abolitionist poem The Slave’s Lament, Burns accepted a position as a bookkeeper on a Jamaican slave plantation in 1786. The success of his Kilmarnock poems drove Burns to Edinburgh rather than the Caribbean (and to marriage with Jean in 1788). He mused what his life as “a poor Negro-driver” might have been like.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat all-important “context” word is dismissed as an excuse, but Burns' life is too multifaceted to dismiss summarily. The real question is whether or not his poetry still has any purchase – if the answer is yes, it is for readers and teachers to find the meaning of the man in his words with as much independent investigation and self-reflection as possible.

If the answer is no, and if you despise who he is and loathe Burns Night, then you must consider his words to find out why others do not. As the man himself advised into A Louse in 1786:

“O wad some Pow'r the giftie gie us, To see oursels as ithers see us!”

•Alastair Stewart is a freelance writer and public affairs consultant specialising in Scottish history, devolution and UK politics.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.