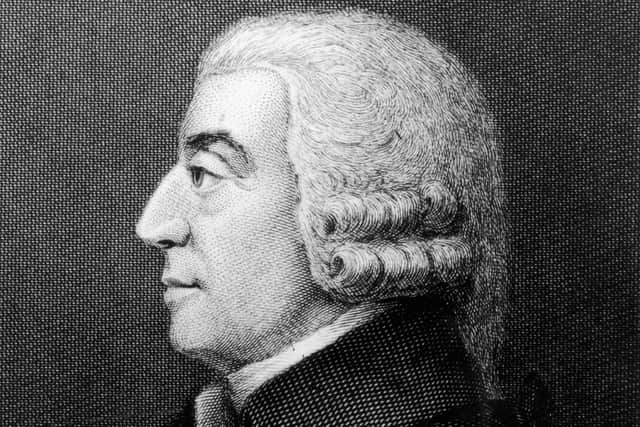

Adam Smith: Why it is unfair to label Scottish economist and philosopher a proponent of 'greed is good'

The 300th anniversary of Adam Smith’s birth last month coincided with a crisis in capitalism.

Amid wealth inequality and the climate crisis, neoliberalism is being critiqued from across the political spectrum. It seems the right time to question the neoliberal interpretation of Adam Smith as the father of capitalism and a supposed advocate of a central tenet of free market thought: “Greed is good.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdClearly neoliberals, such as Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman got this wrong, and they are also wrong that Adam Smith was on board with such a brutal, modern concept. He believed greed was a necessary part of market mechanics but, contrary to the neoliberal reading, his work was an attempt to find ways to rein in commercial greed to support the agrarian order, which he believed to be inherently more ethical and productive than business.

Today, American economist Gregory Mankiw’s best-selling economics textbook cites Smith in making his own claim that greed, or self-interest, leads to “desirable market outcomes”. If one cherrypicks extracts from Smith, it sounds like the 18th-century Scotsman agrees. He is famous for saying “it is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest”. Such a person “intends only his own gain” and is “led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention”. He also wrote that governments should never “attempt to direct private people in what manner they ought to employ their capitals”.

Smith studied, recognised, and explained the importance of greed in the process of wealth creation, but rather than celebrating it, warned it could undermine healthy economies. “The policy of the monopoly is a policy of shopkeepers,” he said, meaning the very butcher, baker, and brewer that some have erroneously thought he unconditionally celebrated. Precisely because of their greed, Smith warned the interests of merchants and manufacturers were “never exactly the same with that of the public” and that they “have generally an interest to deceive and even to oppress the public”.

Smith sought to outline how an agrarian-dominated system could deal with this threat. In doing so, he was looking out for his own interests and those of his patrons. He came from a family of small landowners, and worked assiduously for Scotland’s most powerful landowners. As a professor of moral philosophy in Glasgow, where he taught the children of the landed elite, he acted as an advisor to his patrons, the Duke of Buccleuch and a future prime minister, the Earl of Shelbourne, who later got him a job as a customs tax collector. Smith’s philosophy showed how commercial culture could work within the agrarian regime of the British ruling class. Central to this was the idea of finding a system not based on greed, but which would subsume greed for the greater good.

Smith saw economies as creating wealth through self-interest, supply and demand, but it worried him and he sought to teach an ethic opposed to greed. He called merchants, manufacturers and artisans an “unproductive class” as “no equal quantity of productive labour employed in manufactures can ever occasion so great a reproduction” as agriculture. Farming was the true and most moral source of wealth because nature literally helped it produce. Manufacturing, on the other hand, was not helped by nature and was spurred by human greed. “In them nature does nothing; man does all,” he wrote.

In his 1759 Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith quoted Stoic philosophers to describe the ideal person to be an impartial, moral spectator able to resist vices such as greed, feel sympathy for the common people, and act in a disinterested way. The person who embodied Smith’s ideal of virtue was not the merchant, but rather the “country gentleman”. Such a landlord was never greedy because all capital investments made to improve the land helped the country, the public good, and created essential wealth. Smith believed that agriculture had an internal morality as it created wealth within the country and supported the existing social order.

Perhaps because it is so foreign to modern notions of capitalism and wealth creation, economists and neoliberals today ignore the central argument of The Wealth of Nations that agriculture is the true source of wealth. But Smith repeats it over and over. “No equal capital puts into motion a greater quantity of productive labour than that of the farmer.”

For Smith, virtue lay in what was both productive and advantageous to society, and this was neither greed nor commerce alone. Agriculture’s economic dominance mattered in countering the greed of manufacturers because the landed class produced what Smith idealised as society’s disinterested leaders. The entire point of a leader of society was to support Stoic virtues: “The first of those causes or circumstances is the superiority of personal qualifications, of strength, beauty, and agility of body; of wisdom, and virtue, of prudence, justice, fortitude, and moderation of mind."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn keeping with earlier English philosopher John Locke, Smith’s great inspiration, politicians should support civil government by protecting this natural order and making sure the greed of merchants pushed wealth back towards farming. A government dominated by such guardians of the status quo could stop greedy “statesmen” from trying to create monopolies through immoral and unproductive governmental regulations.

Born from leading landowners, a great moral legislator would be a “man whose public spirit is prompted altogether by humanity and benevolence, [who] will respect the established powers and privileges even of individuals, and still more those of the great orders and societies, into which the state is divided”.

The invisible hand was not simply self-interest, or supply and demand, but rather Smith’s 18th-century, agrarian vision of a good society. While Smith’s ideals seem a long way off, he understood the challenges of a commercial system based on self-interest.

It could produce vast wealth, but also had dangers. To both harness and counter greed, strict moral discipline and sympathy for others were necessary. Smith’s agrarian oligarchy, or any oligarchy for that matter, is not very attractive, but we might do well to emulate his idea that a strong moral, societal response to greed is.

•Jacob Soll is professor of philosophy, history and accounting at the University of Southern California and author of Free Market: The History of an Idea

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.