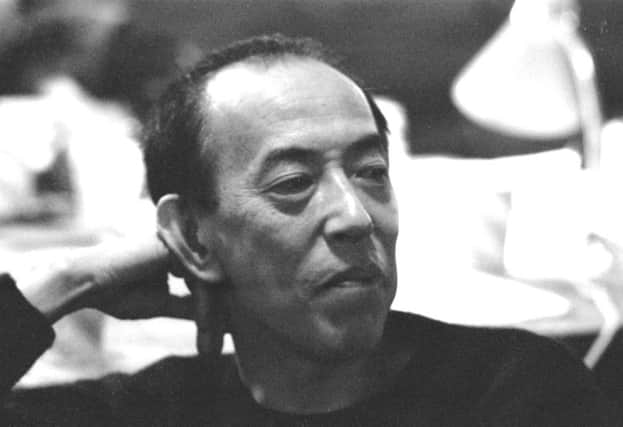

Obituary: Yukio Ninagawa CBE, theatre director

Yukio Ninagawa was an internationally renowned Japanese stage director best known for his interpretations of Shakespeare plays and Greek tragedies who became a regular attraction at the Edinburgh International Festival (EIF). Such was his fascination with Hamlet, he produced it on eight occasions, explaining, “Eight times is not enough. It’s a play that means different things to me, depending on my age.”

Celebrated at home, he first gained international recognition following his samurai-style version of ‘Macbeth,’ his first production to travel overseas, performed at the 1985 EIF where audiences saw actors perform in Japanese kimono with a giant Buddhist altar and were left in awe by the use of vibrant colours such as the falling cherry blossoms to suggest magic, madness and doom. The piercingly beautiful production was an overnight sensation – it was a coup for festival director Frank Dunlop.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNinagawa was noted for his extraordinary visual sense and he went on to become revered for his unique ability to successfully blend and interweave the traditions of the East (Noh), with its exotic effects, and West into his productions of Shakespeare, Ibsen and Euripides, and works by modern Japanese authors, including Kunio Shimizu and Haruki Murakami. Ninagawa described his stage craft as, “The past runs in tandem with the present; actuality in a dream.” He called it “metatheatricality”. Over the next 30years, he brought 17 productions to the UK alone, usually to Edinburgh and London.

Born in the city of Kawaguchi, eastern Japan, in 1935, Ninagawa originally wanted to become a painter but failed the entrance exam for the Tokyo University of the Arts. Subsequently, he trained to be an actor and was active until he turned to directing in 1967 when he established his own theatre company, ‘Gendaijin-Gekijo’ - Modern People’s Theatre.

Two years later, he made his directing debut with the play ‘Shinjo Afururu Keihakusa’ by Kunio Shimizu. In 1972, he founded the theatre company ‘Sakura-sha’ (Cherry Blossom Co), which proceeded to continue the small-theatre movement of the era by presenting Shimizu’s socially controversial plays.

The watershed moment came in 1974, when the theatre producer Tadao Nakane invited him to produce his conceptually daring work on a bigger, more commercial stage. The pair worked on a production of Romeo and Juliet, followed by a version of Peer Gynt, which began in a video arcade and starred a Japanese pop idol. A succession of theatrical hits characterised by dynamic group performances of great visual richness followed and came to be known as the “Ninagawa aesthetic”.

In what at that time was a rare move, Ninagawa produced Japanese-language plays abroad. With ‘Macbeth,’ he moved the action to a 16th-century samurai world dominated by warring chieftains and also changed the usual gloomy surroundings to a thing of wonder, colour and beauty, while making no attempt to down-play the horror of murder, but with the heavy use of music, Bach, Brahms and Fauré, traditionally Japanese. This production went on to further acclaim at London’s National Theatre.

Ninagawa’s next block buster came in 1986 with his sensational production of Euripides’ Greek tragedy ‘Medea’, performed at the courtyard of the Old College at Edinburgh University, with Mikijirō Hira, the previous year’s Macbeth, the lead in an all-male production; it featured Japanese-inspired costumes as well as the use of authentic Japanese music with a Bach suite and incredible visual flair culminating in the climactic image of Hira’s Medea soaring through the night-sky in a dragon-winged chariot.

Two years later, he brought his version of ‘The Tempest’ to Edinburgh. Set on the island of Sado, traditionally a place of exile, Ninagawa wowed audiences bringing a highly stylised performance fusing Shakespeare’s last play with a broad range of traditional Japanese theatrical techniques.

1991 saw Ninagawa work with British actors for the first time in Peter Barnes’ version of Shimizu’s ‘Tango at the End of Winter’. Performed both in Edinburgh and London to critical acclaim, it featured Alan Rickman’s portrayal of an actor who abruptly quit the stage to live in a mist-swathed, dilapidated cinema haunted by dreams. He later worked with the likes of Michael Sheen (Peer Gynt), Michael Maloney (Hamlet) and Nigel Hawthorne on the long-running 1999 RSC production of King Lear; this led to his 2002 honorary CBE.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn Japan, he was known for his temper and demanding personality. He was often seen on TV shouting angrily at actors who were not quick enough to grasp what he expected of them. Ninagawa regularly took issue with critics too, even printing his own rebuttals of their reviews. But this anger, born of his passion for moving audiences with the power of theatre, served to fuel his creative prowess to greater heights. This passion is the legacy he leaves behind.

A year ago following surgery to remove fluid from his lungs, Ninagawa commuted between the hospital and the theatre, where rehearsals were underway for his eighth staging of “Hamlet”. Although confined to a wheelchair and an oxygen tube attached to his nose, Ninagawa continued to exhibit the inexhaustible passion for the stage that had inspired such joy, sadness and awe in his audiences. This production was also seen last year at the Barbican in tandem with his production of ‘Kafka on the Shore’ based on a novel by Murakami.

Over the years, he received a plethora of accolades, including an honorary doctorate from the University of Edinburgh (1992), the Medal with Purple Ribbon for contributions to Japanese arts and academia (2001), Japan’s highest cultural award, the Order of Culture (2010); he also became a member of the Shakespeare Globe Council.

A workaholic, he worked until his last breath, determined to direct Shakespeare’s “Measure for Measure,” which was scheduled to open on 25 May in Japan. He died of multiple organ failure caused by pneumonia. He is survived by his former actress wife, Tomoko Mayama, and two daughters.